This article was first published by VEZA.

Plaxedes Masuku, a 34-year-old sex worker in Victoria Falls, has been struggling to make a living for years – and the local police have not made her life any easier.

In June 2023, Masuku says she was at a bar when the police came and arrested her on suspicion of soliciting. She was fined $30 for disorderly conduct, which is more than Masuku earns in an entire night. The fine took her two nights of work to financially recover from, she said.

“I don’t understand why we are arrested when we are (just) working to feed our children,” said Masuku.

The mother of two says in the absence of a traditional education, this is the only job she can do to pay for her children’s expenses.

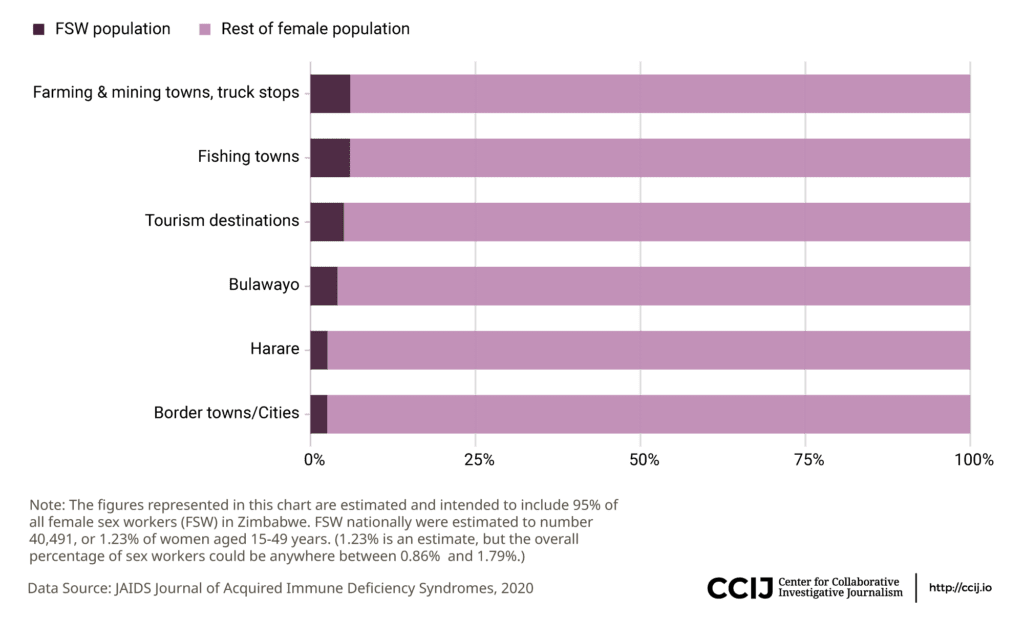

Masuku is not alone in her struggle. About 1% of the Zimbabwean female population aged 15-49 years old are sex workers, and Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe’s premier tourist destination, attracts sex workers from around the country in search of affluent customers on holiday.

Population size of female sex workers (FSW) in Zimbabwe

This chart shows the percentage of sex workers among women aged 15-49 across various “hotspot” sites for sex work nationally.

However, between what she calls “police harassment” and competition from other sex workers, Masuku says it’s getting more and more difficult to make a living.

“What happens if I die now?… I have to live for my children,” she says.

Plaxedes Masuku, a Zimswa Matebeleland North provincial coordinator and sex worker in Victoria Falls, places teddy bear dolls on her bed and applies makeup in her lodging in Chinotimba township

While Masuku may not be able to prevent other sex workers from operating nearby, she says at the very least the police can follow the law and leave her alone when she is simply standing on the street.

A 2016 High Court ruling in Bulawayo involving three alleged sex workers offers a window into the protections Masuku and other sex workers legally must be given. The court ruled that the alleged sex workers could not be arrested and fined for solicitation because their purported clients could not be presented to the court.

The 2016 ruling followed a 2015 decision from the country’s Constitutional Court, which ruled against the arrest of nine women on the charge of soliciting for sex, saying as long as there were no clients who would confirm that they had been approached by the women, the arrests were a deprivation of their liberty and thus unconstitutional. This ruling effectively nullified the charge of loitering for the purpose of prostitution – unless there was evidence of illegal activity.

And yet two rulings that should have limited police prosecution of sex workers appear to have given way to an alternate reality – and not just in Victoria Falls. All across the country – from mining towns, to small villages, to sprawling urban centers, over a dozen sex workers told the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism that they had been subject to police harassment in violation of court rulings.

(Above) Sex workers attending an end of the month meeting organized by the Zimbabwe Sex Workers Alliance (ZIMSWA) speak to CCIJ in Gwanda outside Bulawayo. (Below) A vegetable market in Gwanda.

Additional interviews with advocacy groups, including the Sexual Rights Centre (SRC), Zimbabwe Sex Workers Alliance (ZIMSWA) and Katswe Sistahood, along with an analysis of 272 legal documents, further reveal systemic issues and persistent violence against sex workers in Zimbabwe, including patterns of police abuse and societal stigmatization. At least nine court cases over the last two decades also highlight a significant lack of adequate legal protection for sex workers within the judicial system.

SRC Director Musa Sibindi said there may be an explanation. Although the 2016 court ruling helped to reduce the number of arbitrary arrests for loitering, it fell short of decriminalizing sex work entirely, leaving sex workers vulnerable to continued persecution.

“Abuse can still happen, even if police officers are mindful of the conditions under which they arrest sex workers,” she said. But, she added, police have not been particularly mindful, leaving women like Masuku and her colleagues often in dire circumstances.

National police spokesperson, Commissioner Paul Nytahi, said the police “have always observed the laws of the country and fully take cognizance of the 2016 High Court ruling regarding sex workers.” He added that the police are properly trained to handle sex workers with dignity and respect.

Many sex workers doubt these trainings are making much of a difference and argue more needs to be done to protect them.

“The police officers are often worse than the clients in terms of abusing us,” says Sibongile Hadebe, a 44-year-old Bulawayo-based sex worker.

An inherited legacy of abuse

Though the High Court’s ruling has been in effect for nearly a decade, Khangelani Moyo, a sociologist at the University of the Free State in South Africa, says he isn’t surprised police abuse of sex workers still persists. He says that for decades, dating back to colonial rule, there has been state-sanctioned violence against sex workers – and it is rooted in the broader historical violence that has been perpetrated against black women in Zimbabwe.

The country, he says, was built on patriarchal foundations, and “one of the key aspects of this patriarchy was the policing of women’s sexuality.”

“Initially, (black African) women were not even permitted in the city. They were expected to stay in rural areas, raising children,” he explained. Entering the city, let alone trying to work in it, was considered shameful behavior for black women.

“The very presence of a (black) woman in the city or on the streets marked her as a potential criminal or someone likely to engage in illegal activities,” Moyo said.

Historian Pathisa Nyathi adds that during the colonial period, white police officers patrolled the city streets to make sure there were no black women. In fact, Makokoba, Bulawayo’s oldest township, is named for the white man who used to patrol the area to make sure black women were not there.

“His job was to ensure that nothing (and no one) illegal, especially a woman, was brought into the township, which was initially a bachelor’s township,” he said.

But Moyo says excluding black women from urban spaces – an attempt to keep them out of the central economy, while confining them to child-rearing duties – was not sustainable in the long term. As colonialism expanded, British settlers wanted domestic workers to maintain their homes in the city, and so black women were given jobs inside city limits.

Not every woman who moved to the city found domestic work – or even had male partners to rely on. For those women, sex work became a means for survival, not a desecration of faith, he said.

It was, however, a violation of colonial law, which forbade any and all forms of sex work – considered a public and moral nuisance under the Miscellaneous Offences Act. More specifically, the act stated that any person found loitering in a public place for the purposes of prostitution or solicitation would be found guilty of a crime.

“It is difficult to say exactly how many sex workers were charged because it was (so) routine,” Moyo said. But, he noted, that as recently as the 1990s, women were arrested for loitering, even when they were out at night with their boyfriends. The Miscellaneous Offences Act remained in effect until 2005, decades after colonialism had ended.

It was replaced by the Criminal Law and Codification Act, which still criminalized soliciting or coercing sex. However, a 2024 amendment, which is now part of the law, made a significant linguistic change, replacing the word “prostitution” with “sex work.”

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Otilia Chinyani, a senior program officer at Katswe Sistahood, highlighted the significance of this change. The amendment, she said, recognizes “sex work” as a legitimate – though technically still illegal – form of labor.

While there’s progress yet to be made, she said she is encouraged when laws and policies “are very deliberate in speaking against discrimination, because it’s the same discrimination against sex workers that has left them vulnerable to the different forms of violence that they face.”

However, given the continued alleged abuses of sex workers, Chinyani says there is still much more work to be done to protect them.

Sex workers forced to pay ‘tollgate’

Busisiwe Ncube, a 32-year-old sex worker in Kamativi, a small town that was once a thriving mining community, believes defining her profession as “sex work” doesn’t go far enough.

The sole provider for her four children, she says that getting arrested by police on a regular basis impedes her ability to provide for her family, including her youngest child, who was born in June of this year.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Ncube says that sex workers are frequently arrested by police at bars, and when they target her and her colleagues at those bars, they often demand huge payments in exchange for not filing charges.

“They arrest us, take us to the station, but they don’t write a docket,” Ncube says. “If you have $30, they let you go. If not, you have to do community service” and provide a variety of other services, including sometimes sex.

“What can you do,” she asks. Ncube explains that she and her peers often cannot pay the fines, and each day they spend in jail, they also cannot earn money to pay for their families, so they agree to have sex with the police officers in order to get back to work as quickly as possible.

At least, she says, “they wear condoms.”

Commissioner Nyathi did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding the incident Ncube described.

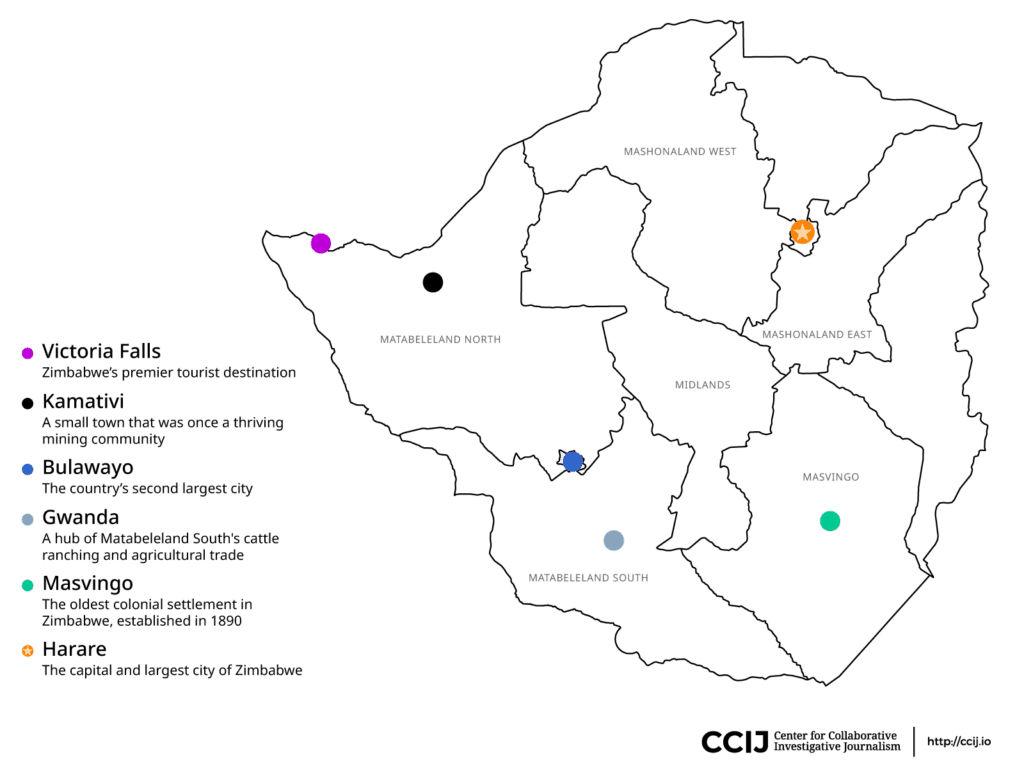

Reported locations where police allegedly abused sex workers

Sex workers from major cities to former mining towns to small villages reported being targeted and harassed by local police.

Faith Madzinga, a 35-year-old sex worker from Masvingo, a mid-sized city in southeastern Zimbabwe, has a more confrontational relationship with the police.

“Sometimes, you’re just walking, minding your own business, and the police arrest you, demanding as little as $2,” Madzinga recounts. Another sex worker in Masvingo, 32-year-old Jenny Chera, says the police call this fee “tollgate,” the price to be paid if a sex worker wants to avoid getting arrested and taken down to the police station.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Madzinga has been arrested multiple times, she says. And she has spent time in jail more than once.

“We were once jailed for 20 days at Mutimurefu Farm Prison for loitering,” she says. “The fine was $200, which I couldn’t afford, so I chose jail.” One of her sons had to visit her in jail, and what he witnessed, she says, was heartbreaking.

“I lost a lot of weight because I had not accepted that I had been imprisoned. The conditions were terrible: porridge without sugar in the morning, and sadza (cornmeal) with vegetables without oil or salt (in the afternoon),” she explains.

Madzinga’s experience underscored the devastating impact such arrests can have on individuals and their families. And if Madzinga had any hopes of finding another kind of employment, her 20 days in jail meant she now had an even longer criminal record, which would make finding another job that much harder.

Nyathi did not respond to requests for comment on Madzinga’s allegations either.

As difficult as Ncube and Madzinga’s experiences were, two sex workers in Bulawayo, the country’s second largest city, shared an even more haunting alleged story of police abuse.

Sibongile Hadebe, a 44-year-old sex worker, and Fiona Msimanga, a 33-year-old sex worker, said that earlier this year they were arrested at a local bar. After the police raided the bar, they gave them two options – pay a fine or have sex with the officers.

“And if you don’t have money, then you will have to pay with sex,” Msimanga said.

Hadebe and Msimanga didn’t have enough money to pay the fine, so they said the police did not take them to the police station. Instead, the sex workers said they were driven to a building under construction in the local suburbs.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

When they arrived at the empty building, Msimanga said they were “made to choose which style (of sex to pay with). We didn’t have many options. We just wanted to be released so that we could go back to work and make some money for the night.”

Hadebe says that isn’t unusual. Often, she says, police do not want to force sex at the station so they take the sex worker somewhere more private, somewhere where they are less likely to be caught.

While Nyathi did not address the specific allegations of the Bulawayo sex workers, he said that as of this year, the police have not received any reports of police abuse of sex workers at the national, provincial, district or station level.

Hadebe says she and Msimanga never reported the incident of assault for good reason. “A sex worker’s case is never taken seriously. We are told isn’t that what we are looking for out in the streets,” Hadebe says.

Nyathi responded by saying “the laws of the country are very clear… if such reports are made, the police will investigate and take appropriate disciplinary action against offending officers, including criminal charges, if necessary.”

Nyathi said the police force remains committed to upholding the laws and performing its duties accordingly.

Sibindi said that while, according to her organization’s records, the number of reported incidents between sex workers and police has decreased since the 2016 court ruling, her organization – the SRC – still continues to receive reports of abuse by the police.

“The sex workers are reporting intimidations, physical harassment, bribes (and) being asked for sex in exchange for avoiding arrest or detention,” she said.

‘How can we fix this?’

Organizations advocating for sex workers believe it’s crucial to pursue full decriminalization of the trade.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Chinyani of Katswe Sistahood says changing the language from “prostitution” to “sex work” in the law this year was a positive first step, but the next step is removing the legal barrier to the profession entirely.

Police will not be able to target sex workers as easily if their very jobs are not in violation of the criminal code. They would also be granted the same legal rights and protections that other workers in other legalized industries have, she said.

Nqobani Nyathi, a legal expert and former SRC legal officer, said decriminalization of sex work will not happen overnight. He says efforts to protect sex worker’s basic rights – such as freedom from arbitrary arrests – are the next step in that direction.

Like Chinyani, he points to the linguistic change in the criminal code, which now refers to their profession as actual work. He says it “reflects a shift in attitudes” and highlights “growing recognition of (sex workers’) human rights, even in a country long influenced by patriarchal norms.”

Barring a major legislative change, Nyathi says the Zimbabwean president can play a part in ensuring police comply with the law by appointing new members to the Zimbabwe Independent Complaints Commission (ZICC). On Sept. 19, Zimbabwean President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa made one such appointment – making former judge Webster Nicholas Chinamora the chairperson of ZICC.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

The commission is tasked with investigating misconduct complaints against security service members – either filed by individuals or on their behalf. The commission aims to enhance accountability and transparency within the country’s security forces, including but not limited to the police.

For Nqobizitha Ndlovu, a lawyer at Cheda and Cheda Associates in Bulawayo, the strengthening of the ZICC means that sex workers now have an executive body that they can take their complaints to in case of arbitrary arrests and abuse by the police.

Many human rights advocates say sex workers cannot wait for the president or the commision to act; they must be their own champions and defenders, and there is work advocacy groups can do to empower sex workers.

Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR), which represents victims of human rights violations, says that it encourages sex workers to pursue legal action against their abusers because legal accountability can force violators to face financial consequences for their actions – and think twice about misbehaving again.

Roselyn Hanzi, director of Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, took to X (formerly Twitter) to encourage sex workers to pursue legal action against their abusers.

“We must normalize hitting perpetrators of human rights violations straight in their pockets,” she wrote in a thread on X. “Why should taxpayers foot the bill for gross human rights violations?”

ZLHR has successfully pursued legal action against the police and the Zimbabwe National Army on behalf of victims of violence in the past, securing monetary awards against individuals for their unlawful conduct.

Hanzi said that when her organization has won such judgments, applications for garnishee orders – which allow a portion of wages to be directly deducted from the offender’s paycheck – have been granted by the courts.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

In Harare this year, one police officer was forced to pay $29,000 in compensation for brutally attacking a protester five years earlier, she said.

“The monetary award is (being) deducted monthly from the salary of the police officer,” Hanzi wrote on X.

And short of pursuing legal action, Ndlovu said, “sex workers must be brave enough to come forward and report these incidents to higher authorities within the police force.”

Until sex workers report crimes to police authorities, he says, their abuse will remain a “hidden crime.” And, he says, it’s next to impossible to prevent a crime authorities do not even know is happening.

Ndlovu says if sex workers are willing to come forward, they should first report the issue to the officer in charge of their local police station. From there, either the officer in charge – or the sex worker if they feel ignored – can escalate it to higher levels of command at the district, provincial and even state levels.

“Obviously, issues of retaliation will always be there,” Ndlovu said. “But they have to choose the better evil” – report and risk retaliation, or remain silent and allow the abuse to continue indefinitely.

Ndlovu says despite what some sex workers may believe, the police have a “robust and strict disciplinary process in place,” which makes it easier for cases, once reported, to be monitored.

This process, he added, also opens avenues for NGOs to track cases, reducing the risk of them being dismissed or swept under the carpet, and offering some protection against potential retaliation.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Changing the narrative

However, sex workers and advocacy groups maintain that all of these solutions won’t change that status quo until Zimbabweans accept sex workers into society – without any stigma or judgment.

A human rights activist, Effie Ncube, says one way to approach that is to give sex workers a platform to tell their stories, including in newspapers, during radio broadcasts and on television. He says sex workers can also create their own platforms through alternative media – like plays, podcasts and music.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

Ncube says both approaches can help humanize sex workers – portraying them as ordinary and relatable individuals with families, aspirations and struggles. As Zimbabweans develop a deeper understanding of sex workers’ lives, they can begin to advocate for fair treatment of them in society.

Stories that also show the impact of abuse, discrimination and violence against sex workers can raise further awareness about the harm caused by societal prejudice and possibly lead to more informed public discussions around the issue, Ncube adds.

Short of changing society, sex workers like Masuku in Victoria Falls, say they can build their own sisterhood to support one another, even if they do sometimes compete for work. And there are organizations that exist to help facilitate this work.

The Centre for Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Research Zimbabwe conducts peer workshops where sex workers meet as equals and discuss the challenges they face – while exploring ways to navigate the profession as safely as possible.

But they also learn skills that might give them other career opportunities. Katswe Sistahood, for example, offers sex workers classes in dressmaking, so they can learn how to sew and design clothing.

For Masuku, these peer workshops are about looking beyond the present. They are geared toward preparing for “how we might eventually move on from this work” and start a new chapter without the looming fear of police abuse “hanging over us,” she said.

Photograph by Aaron Ufumeli/CCIJ

This investigation was produced with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy.