By Mandlenkosi Mpofu, Zenzele Ndebele and Bhekizulu Tshuma

Marry Ndlovu’s memoir is titled quite fittingly considering what she goes on to deliver. But we chose it as the first book we will review for this magazine because we think in very specific ways, it is a work that says ‘Yithi Laba’ (Yes, We are the Ones Who Fought and Shed Blood for this Country).

It is an account of joy and tears, and of love and anger (or if you like hatred/hate) all intertwined such that too many emotions are evoked at the same time.

The narrative is so rich and complex that in this review, we could only pick a few themes. But more importantly, it is an account that tells the sad fate of the ZAPU and ZPRA cadres who fought gallantly for Zimbabwe to be free.

When independence was delivered, they were not only banished to the margins of the new state, but were hunted down, hounded and humiliated. Then they had to watch those triumphantly claiming the prize going on to systematically destroy the state and the country, and to eventually wreck the futures of many generations in whose name sacrifices were made.

Zimbabwe’s liberation struggles have been recounted numerous times, in historical accounts that mainly privilege the role of ZANU and its military wing ZANLA.

In these accounts, it is mainly the heroic acts of ZANU/ZANLA leaders such as Herbert Chitepo and Josiah Tongogara that are extolled.

On the side of ZAPU, it is fair to say there is begrudging acknowledgement of the role played by Nkomo, which mainly becomes important because after all he signed that Unity Accord.

Outside that, as a nation, we have been subjected to very little about the acts, heroic or otherwise, of those who were in ZAPU/ZPRA, to the point that there are history books that declare acknowledgement for ZPRA’s ‘minimal’ contribution.

This lack of balance has seen one side of our liberation struggle told into films, folklore and examinations for various levels in our children’s schooling.

However, it is not only in its departure from the mainstream, ZANU and ZANLA-centric narration of the liberation struggle that Mary Ndlovu’s beautifully written memoir is so important.

More importantly, this memoir explains to us, in vivid ways, what the leaders and then the masses, expected as the fruits of their independence. It then goes on to describe that independence for us, from the beginning in 1980 and the early years, and then onto its teens and early adulthood.

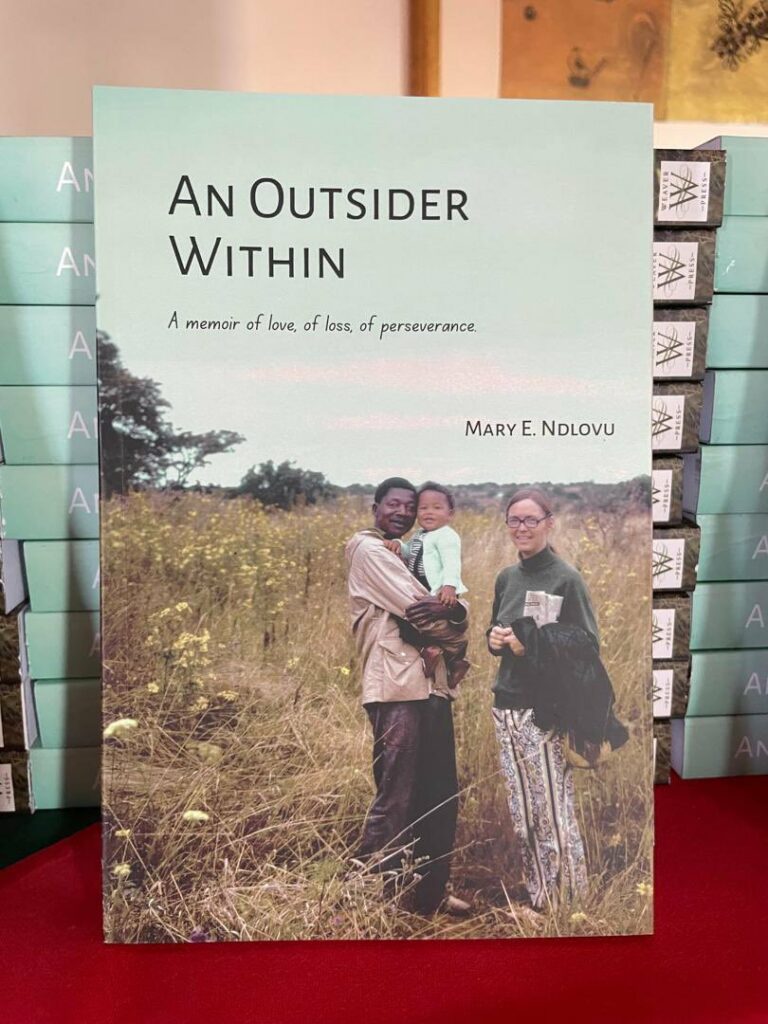

It is a beautiful memoir because it is a story of love, between Mary and her beloved Edward Ndlovu, whom we can say this book is about.

Edward can best be described as one of the engines of the ZAPU machinery in the liberation struggle.

Mary describes how this giant, in physical stature, intellect and contribution to our independence worked tirelessly with his colleagues in Lusaka to deliver independence.

Where ZAPU/ZPRA roles are explored through individual heroes, we are used to reading about more prominent leaders such as Nkomo, Jason Moyo and George Silundika.

Mary’s book shows how behind these household names were lesser-known individuals without whose contribution not much would have been achieved.

However, we found this story to be one also filled with sadness because it gives us glimpses of what could have been, of the Zimbabwe we could have had instead of the shell we are called upon to give patriotic praise to.

After returning home at independence, Mary and her family had to live through fear and anxiety in the 1980s, where ZAPU and everything it represented became an enemy bigger than even the white colonial enemy that had led to the armed struggle in the first place.

In this, Mary manages to use the memoir to voice the experiences of everyone who endured the Gukurahundi atrocities.

The story ends in the 2000s, when Zimbabwe, now the entire nation, faced the calamitous crisis of a collapsed economy and a belligerent, reckless political elite that we are still going through.

Through the experiences of her own family – her husband and her children and her husband’s extended family in Gwanda and in Bulawayo, we read the lives of everyone in Matabeleland and maybe Zimbabwe as a whole, whom independence disappointed.

The story is rightly incomplete. It ends with Mary finally leaving Zimbabwe and returning to Canada, her native country.

She had met her beloved Edward in a chance encounter in Lusaka in the mid-1960s. They had married and started their family there while the fight for independence was raging, knowing that when Zimbabwe was delivered, they would go ‘home’ and build a future for themselves and their children.

It was those children who left first.