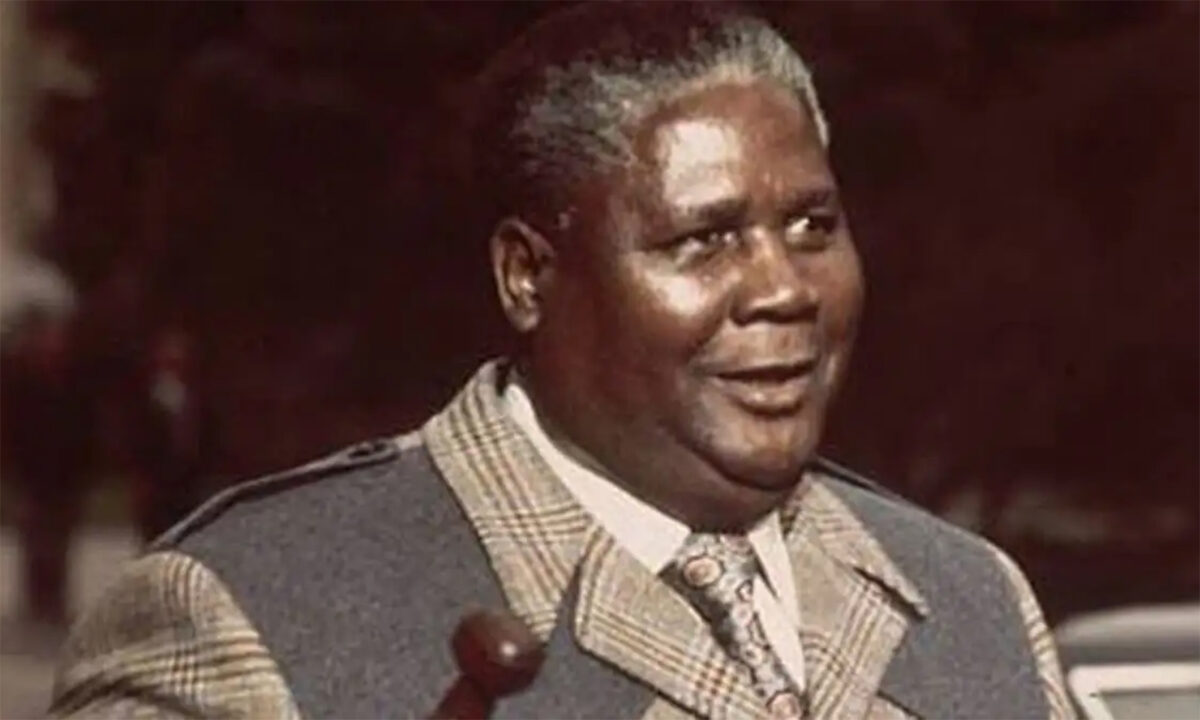

The Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZPRA) was born from the nationalist struggle led by Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) in the 1960s.

Contrary to stories perpetuated at independence that ZAPU lacked the will to fight, and then used as the scapegoat for the real reasons behind the breakaway led by Enos Nkala and Ndabaningi Sithole in 1963, historians have shown that by then, ZAPU had already laid the groundwork for armed resistance.

Numerous biographies and historical accounts by former ZAPU cadres and commanders, as well as by former Rhodesian Front soldiers, have also attested to ZAPU’s immense role in the armed struggle. Sadly, from independence to date, the Zimbabwean establishment has used school textbooks, songs, folklore, state media and many platforms to promote the narrative that ZANU and ZANLA fought the liberation struggle alone, with ZAPU and ZIPRA relegated to footnotes.

It was in 1962 that Nkomo entrusted James Chikerema to launch a clandestine military wing, the “Special Affairs”, which became the foundation of the liberation struggle led by ZAPU. Between 1962 and 64, many weapons were smuggled to the front, mainly from Egypt. Around this period, the first batches of ZAPU recruits were sent for military training to countries like Russia, Ghana, China, Egypt, and Cuba. Some of these cadres – such as Dumiso Dabengwa and Solomon Mujuru, who was at the time known by his nom de guerre, Rex Nhongo – would go on to become prominent figures in the history of the struggle.

This groundwork bore fruit in September 1964, when a ZAPU sabotage unit led by Moffat Hadebe carried out one of the first armed attacks in Rhodesia. In a different country, Hadebe would be a household name with many streets named after him.

This early start and the well-documented role of ZPRA in the military struggle debunks the carefully choreographed narrative that ZANU’s founders broke away from ZAPU because they were the sole “radicals” pushing for war, against Joshua Nkomo’s ‘moderate’ leadership. The reality was that the armed struggle was a central issue to Nkomo and others in his inner circle, as it was to those who formed ZANU, although the two groups followed divergent ideological paths.

ZAPU’s armed wing was revamped and transformed into ZPRA after a turbulent period of internal crisis in which another group of rebels led by Chikerema formed the short-lived FROLIZI. Jason ‘JZ’ Ziyaphapha Moyo, a veteran nationalist, took charge of ZAPU’s external operations following Chikerema’s 1971 defection. JZ then led the reorganisation of the military wing, which was renamed “ZPRA” in 1972. Until then, it had been called the Special Affairs Department, with Chikerema as caretaker leader.

ZPRA’s founding leadership featured commanders of considerable calibre. Perhaps the most prominent was Alfred “Nikita” Mangena, the firebrand military leader who was recognised as one of the most brilliant guerrilla commanders among liberation movements in Africa. Mangena, ZPRA’s first Chief of Staff in the 1970s, assumed command of ZPRA and is credited with building and stabilising a professional fighting machine from the Special Affairs.

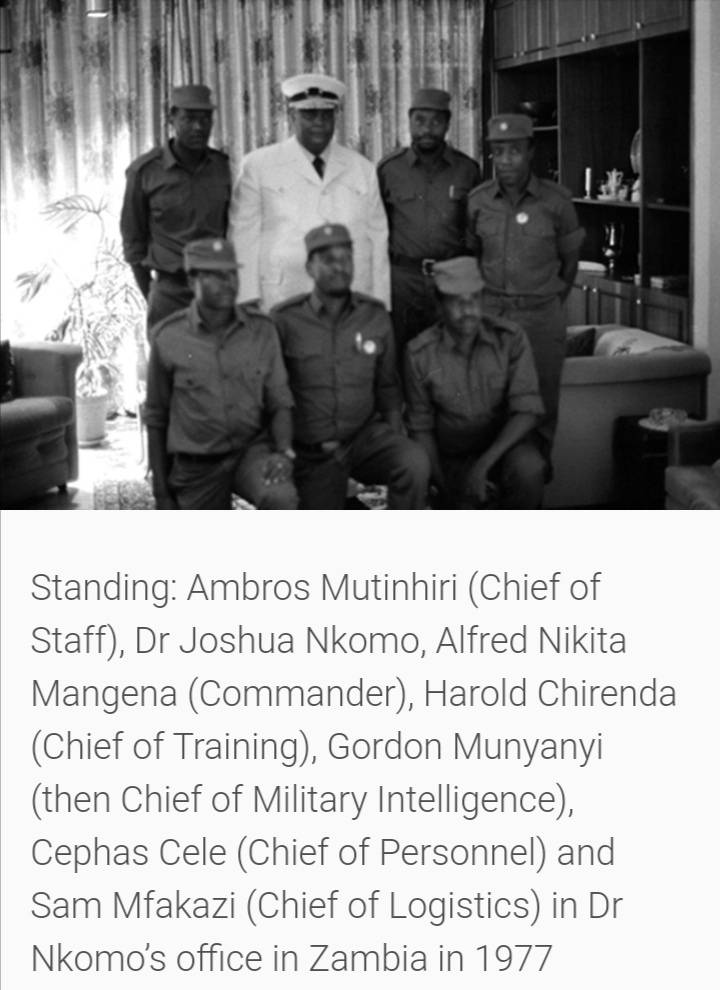

Apart from reshaping the military wing’s structure to ensure more intelligence coordination and smooth reconnaissance and logistical support on the battlefield, Mangena also transformed the organisation to meet the challenges of conventional combat. After his untimely death in 1978, Mangena was succeeded by Lookout Masuku, who led ZPRA into independence and was persecuted by the new ZANU government until his controversial death in 1986. Several luminaries of the Zimbabwean armed forces also held leadership positions in ZPRA. They include Ambrose Mutinhiri, who rose to the rank of Brigadier-General in independent Zimbabwe, Lookout Masuku, Javan Maseko, Swazini Ndlovu, Gordon Munyanyi, Harold Chirenda, Sam Mfakazi, and Cephas Cele.

Unlike many guerrilla movements, ZPRA commanders emphasised discipline across the ranks. To achieve this discipline, a solid organisational structure was therefore required, in which a balance was sought between bureaucracy and the flexible operational efficiency required in guerrilla combat.

ZPRA was therefore organised to resemble a conventional military hierarchy. The commander had organised departments for operations, intelligence and logistics, which mirrored the style favoured by the Soviet army. Under the training of Soviet and Cuban instructors, ZPRA was transformed into a formidable force. Instead of training in ideologies and sloganeering, ZPRA officers received training in conventional capabilities such as conventional infantry manoeuvres, the use of heavy weapons, engineering, sabotage and intelligence gathering.

Some units were also equipped with traditional armoured vehicles and military tanks. The result was a blend of guerrilla and conventional tactics for which ZPRA became distinguished. This was in line with ZAPU’s vision that, whereas guerrilla warfare would weaken the enemy, traditional warfare was needed as the final phase of the struggle, to deliver the final blow and eventual takeover of the country.

The level of training received by ZPRA fighters can be gleaned from the glowing accounts given by the liberation forces they collaborated with in the region, such as the ANC’s MK and SWAPO’s People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). Through such alliances, ZPRA provided transit and safe havens for MK cadres, and many missions were carried out in collaboration. It is common knowledge, for instance, that by the late 1970s, ZPRA had opened a southern front in western Zimbabwe, which became a “corridor” through which MK fighters could slip onto South Africa’s frontiers.

ZPRA’s command culture and discipline became a hallmark of its identity, with Nikita in particular standing out among its commanders as a strict disciplinarian who did not suffer fools. This discipline was anchored on many important aspects of ZPRA’s leadership, among which was ensuring that its combatants were catered for to the best of the leadership’s ability, in terms not only of weaponry but their basic needs such as clothing, food and other logistics. ZPRA’s officers were also highly trained, and many were also very educated, as ZAPU sent military leaders for cadet training and even for academic studies, in preparation for transformation into a professional army in an independent Zimbabwe.

The discipline that was instilled in the force was also replicated in ZPRA units’ relations with the communities where they operated, which were marked by professionalism and respect towards the people.

Despite their superior training and professionalism, ex-ZPRA commanders and soldiers were either purged in numbers from the army very soon after the ZNA was constituted. Those who remained were marginalised and, in some cases, suffered levels of persecution that drove them to desert the army. The result was that ZPRA’s influence in the ZNA became minimised.

Every time I read such articles on Zpra and Zapu, I feel it’s an affirmation that this country was deprived of an opportunity to remain the jewel of Africa that it was before independence.

At independence, a Federal system of governance should have been established. If not Matebeleland and Midlands should have separated from the rest of the country. Then our culture and dignity would have remained intact