By Nyasha Dube and Priscilla Makondo

Twenty-six-year-old Agneta Ndlovu recounts the traumatic experience of delivering her first child at Mandava Clinic, recalling the ordeal as a ‘living nightmare’ after being denied care due to her inability to pay a bribe.

The unemployed Ndlovu from Fourmiles on the outskirts of Zvishavane town in the Midlands Province was being punished for failing to raise US$5 commonly known as mari yambuya (the midwife’s money) while admitted at the facility.

She said nurses at Mandava Clinic, which is affiliated to Zvishavane Ditrict Hospital, told her that they were only giving priority to those who were able to pay the bribes.

Ndlovu said she was in labour for three days where the midwives watched her writhing in agony and refused to help her for failing to line their pockets.

“I was in labour for three days at Mandava Clinic and when I gave birth, I faced neglect,” she recalled. “On the third day, I gave birth on my own. I called for help, but no one came.

“The biggest challenge is that the midwives demanded (money for drinks). “I couldn’t afford to pay them.

“Others who were at the same ward and had paid were being treated well by the midwives.”

Investigations by CITE revealed that Ndlovu’s ordeal was not an isolated case. Fairness Moyo (36), an expecting mother at the same clinic, said the midwives also demanded a bribe from her.

Moyo said pregnant women were made to pay various amounts for sundries and the money was never properly accounted for.

“Women are being asked to pay extra fees called mari yambuya,” she said. “If you don’t pay, you don’t get monitored. They just ignore you.

“They make you buy things such as cotton wool in big quantities and whatever is left unused is then sold to other patients at inflated prices.”

She claimed that some health care workers, especially those on night duties, sold medication they obtained from other patients through coercion.

Investigations revealed that staff at Mandava Clinic can insist on paymemt for services pregnant women such as Ndlovu and Moyo should be receiving for free from public institutions.

These include fees for changing linen, injections, priorisation in queues for treatment, getting better care and acquiring susbsidised medicines.

Corruption endemic in health sector

In 2017, President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced the scrapping of maternity fees at public hospitals, but the implementation of the policy has been hampered by corruption and government’s failure to adequately fund the health sector.

A Transparency International Zimbabwe 2021 report titled: Corruption in the Public Health Sector in Zimbabwe, said petty forms of corruption such as bribery or facilitation fees revealed structural problems in the health care system.

It said the problems included, but were not limited to over regulation, low salaries, inefficient or lack of rules and regulations, lack of accountability and inadequate services.

“Over the years there has been a general rise in citizens resorting to bribery to acquire services in Zimbabwe,” the report said.

“Findings from this research revealed that the public health sector is no exception.

“Petty corruption in the health sector continues to affect the quality-of-service delivery and the realisation of health targets.

“Seventy percent of the respondents indicated that they had been asked to pay a bribe while accessing health care services at public hospitals.”

For Ndlovu, the experience at Mandava Clinic was the final straw that broke the camel’s back.

“Next time I will opt for a home delivery,” she told CITE. “At least there, I will get undivided attention. In clinics, if you don’t pay, you die.”

Home births are common in rural Zimbabwe due to high health care costs, long distances to clinics and cultural or religious beliefs, leading to high maternal deaths.

According to the Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey 2010/11, the country’s maternal mortality rate is extremely high at 960 deaths per 1 000 live births, translating to about 100 women dying every day of pregnancy-related complications.

This is three times as high as the global average of 287/100 000 and almost double the average for Sub Saharan Africa (500/100 000).

The United Nations Population Fund says while globally there has been a 34 percent decline in the maternal mortality ratio from 1990 to 2008, Zimbabwe has experienced an increase from 283 deaths per 100 000 births in 1994 to 960 deaths in 2010/11.

A 2007 Zimbabwe Maternal and Perinatal Mortality Study established that the risk of a maternal and or a neonatal death is increased by delivering outside a health institution.

Homebirths are common and risky

Home birthing is especially rampant in rural areas recording 42 percent compared to 14 percent in urban areas, with high costs cited as one of the biggest factors for pregnant women choosing to give birth away from health facilities.

Included in the costs are the bribes and informal payments that drive women like Ndlovu away from health facilities to give birth under risky conditions in their homes.

A senior official at the Zvishavane District Hospital, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said corruption by midwives was being fueled by lack of medicines and other sundries at the health facilities.

The official said the government’s waiver of maternity fees was not accompanied by requisite funding to health institutions.

“This issue of bribes disguised as mari ya mbuya is prevalent,” the official said. “The government says maternal health is free, but institutions have no supplies, not even something as basic as gloves.

“So midwives ask women to bring their own. When they don’t, they ask for payments.

“Public hospitals fail because the gap between policy and funding is too wide. Nothing is really free.”

He said at times health facilities were overwhelmed by the number of patients seeking treatment at the government-run facility, opening the door for corrupt health workers to take advantage of the chaos.

“At one point we had 38 women in a maternity ward in a single day,” the official said. “How do you feed them, what sundries do you use when there is nothing?

“It’s useless to say maternal care is free if the (Health and Child Care) ministry doesn’t provide resources.”

Understaffing fuels corruption

Mandava Clinic is severely understaffed, investigations revealed. The clinic usually operates with a team of three nurses, who are scheduled for 12-hour shifts.

It is the only government-run clinic in the mining town and services areas such as Mandava, Highlands and Platinum Park. Zvishavane Town has a population of nearly 60 000 with 52 percent of them being women, according to the 2022 census.

About 19 193 of the women in that area are of childbearing age.

Patience Nkomo, the sister-in-charge at Mandava Clinic, said the facility was understaffed and faced shortages of medicine.

“We are really understaffed, sometimes three nurses for a 12-hour shift with many patients,” Nkomo said.

“Supplies are a big problem. Women can’t afford the fees, so they come very late, sometimes only during delivery. That increases home births.”

However, Nkomo denied allegations that nurses were in the habit of demanding bribes from patients.

Peter Hove, an official from the Zvishavane Residents Association, blamed lack of adequate facilities for the plight of expecting mothers and lack of medication.

“It’s a sad situation,” Hove told CITE. “A few institutions are servicing a large population.

“There is a shortage of staff, medication, and equipment.

“We call on the government to take health issues seriously and allocate more funds. Health care is a right, not a privilege.”

Tapiwa Maurayi, the Zvishavane district medical officer (DMO), said pregnant women only paid a nominal fee US$40 and those who were not able to pay are not turned away.

“Expecting mothers are required to pay US$40,” Maurayi said. “Those who can pay, pay, but those who cannot afford still get the services.

“We just encourage the women to pay as this money covers all the supplies needed for a safe delivery.

“The $40 covers everything, including ultra sound scan and all the supplies needed.”

The DMO was the district had not received any complaints about the alleged demands for bribes by health care workers at any of the facilities.

“Corruption is not allowed, and we have not received any official complaint from the women,” Maurayi added.

“Those ordered to pay bribes should just say no and report to us rather that perpetuating corruption.

“If we receive a complaint we will act. We have zero tolerance to corruption.”

A macrocosm of a national crisis

The crisis at Mandava is a microcosm of a long running crisis in Zimbabwe’s health delivery system, which has been brewing for over two decades.

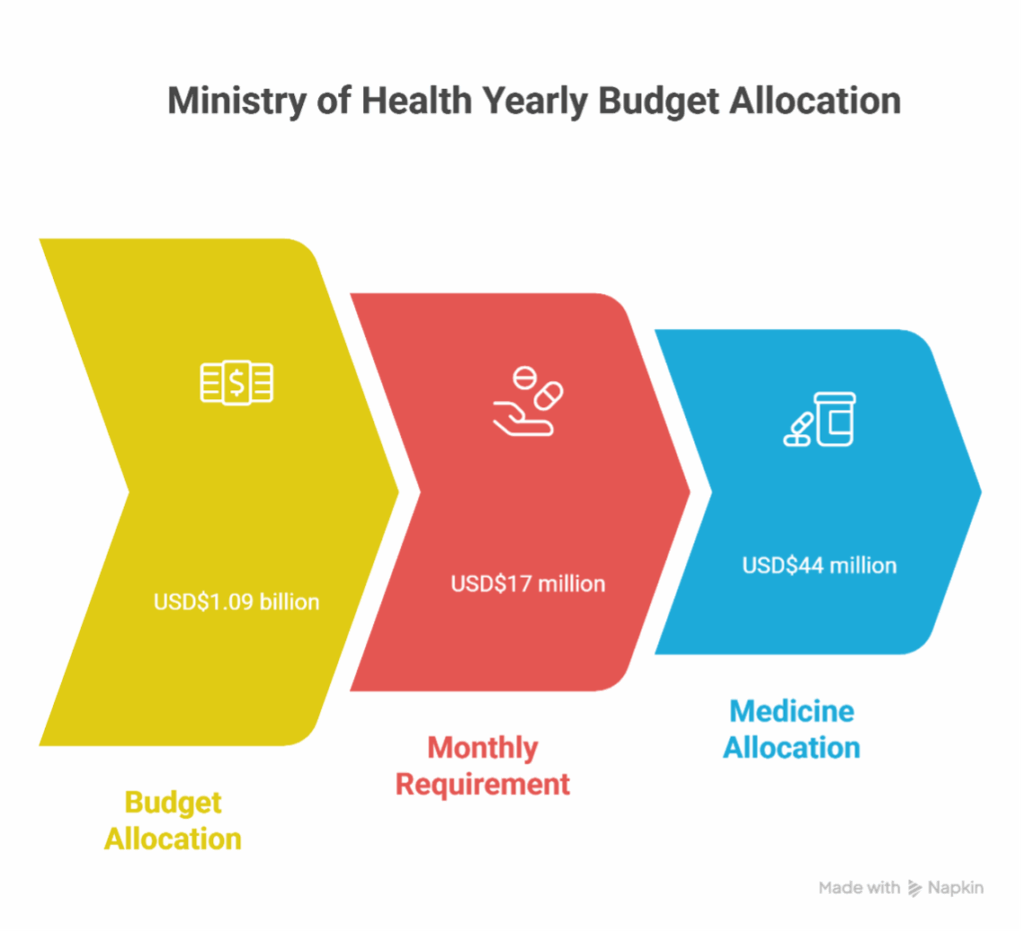

Mnangagwa’s government has been accused of consistently allocating the Health and Child Care ministry inadequate money in the national budget.

In 2025, the ministry was allocated ZiG 28.8 billion (US$ $1.09 billion at the time).

Yet in March, the ministry admitted it needs US$ $17 million every month for medicine alone, a total of US$ $204 million annually.

Only US$ $44 million was allocated for medicines for the entire year.

Zimbabwe has consistently fallen short of the African targets set in the Abuja Declaration, which requires countries to allocate at least 15 percent of their national budget to health.

With the depreciation of the ZiG currency and the withdrawal of external funders like USAID, the crisis is set to deepen.

Kuyalamula uSomandla. Lokhu kuhlazimulisa umzimba. Yimpilo bani le esiphilwa ezweni kodwa?