Lwazi Ndebele says she decided to join the great trek to South Africa after her village located along Zimbabwe’s border with Botswana experienced two years of successive droughts and putting food on the table became a daily struggle for her family.

Ndebele left Empandeni in Matabeleland South’s Mangwe district in 2018 for South Africa’s major economic hub, Johannesburg, where she found a job at a restaurant just before Covid-19 struck two years later.

“I have not been back home since that time,” Ndebele said. ”Two years after I arrived in Johannesburg there was Covid-19 and the borders were closed.

“I have not been able to find a steady job since then to raise enough money to be able to return home.”

Returning home is an option that she is not willing to consider for now because parched Empandeni village offers very little opportunities for young people like her.

Mangwe is bordered to the north by Bulilima district, to the south by South Africa, to the east by Gwanda district, and to the west by Hwange district.

The district is primarily rural, with agriculture being the mainstay of the local economy and the area has a history of recurrent droughts that have significantly affected agriculture and livelihoods, particularly during the 1990s and early 2000s, with notable drought years including 1992, 1994, 2002, 2008, 2016, 2019 and 2024.

These droughts coincide with the district’s semi-arid climate, characterised by average annual rainfall ranging from 400 to 600 mm, rendering any form of subsistence farming unviable.

Empandeni village is about 52 kilometres from Plumtree, a transit town with very little economic activity to offer employment opportunities for young people from the surrounding villages like Ndebele, which makes neighbouring South Africa and Botswana the only viable options for the army of job seekers.

An investigation by CITE with support from the Information for Development Trust (IDT), a non-profit organisation supporting investigative journalism in Zimbabwe and southern Africa, revealed a growing trend of environmental refugees originating from Matabeleland South, which is largely ignored in the country’s migration crisis discourse.

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) records for 2024 showed that 52 percent of the people who left Zimbabwe were coming from Matabeleland South.

https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/flow-monitoring-report-iom-zimbabwe-september-2024

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), an environmental refugee is a person who has been forced to flee their home and community due to changes in the environment, such as frequent droughts.

1,2 billion to be displaced

A global think tank, the Institute for Economics and Peace, predicts that 1.2 billion people could be displaced around the world by 2050 due to climate change and natural disasters.

Although there are no statistics on the number of Zimbabweans that have been forced to migrate to other countries due to the now frequent droughts and other adverse weather conditions caused by climate change, millions of Zimbabweans have been forced to move to different countries because of hardships.

South Africa’s 2022 population census showed that there were now 1.012 million Zimbabweans living in the neighbouring country, which translated to 45 percent of the immigrant population in that country.

A significant number of Zimbabweans living in South Africa are undocumented, which means that a huge proportion of immigrants from this country were not counted during the census.

Thousands others live in countries such as Botswana, Namibia and Zambia as well as overseas.

According to the Zimbabwe Statistics Agency (ZimStat) 2022 Population and Housing Census preliminary results, Matabeleland South, with a population of 760 345, had by far the highest number of households with people that migrated to other countries at 32.6 percent of the national figure.

Matabeleland North followed at a distant 24.2 percent, Masvingo (22.7) percent) and Bulawayo (21.7 percent.).

ZimStat established that although the migration started as far back as the time of the country’s independence, the figures have been on a steady increase since the 1990s when droughts became more frequent.

Unemployment is the biggest push for Zimbabweans to leave the country with the census preliminary report noting that 84 percent of the people that left the country were looking for jobs.

South Africa was the major destination with 85 percent of the Zimbabwean migrants being based there followed by Botswana (five percent) and the United Kingdom (three percent).

Why people are leaving

Over the years the government has been accused of not taking the root causes of people of Matabeleland leaving the country in big numbers seriously with former president Robert Mugabe in 1996 dismissing it as just a culture in the region.

In 2015, Mugabe sparked outrage when he said Kalanga people, a dominant ethnic group in Matabeleland South, were criminals who lived off by carrying out violent robberies in South Africa.

Dr Khanyile Mlotshwa, a Zimbabwean-born academic at South Africa’s University of KwaZulu Natal, said the environment was the biggest push behind the high levels of migration from Matabeleland even before independence.

Mlotshwa does research in social and political philosophy, epistemology and ethics.

He is currently involved in a project titled The constructions of black citizenships in post-apartheid South African print media vis-à-vis migration and urbanisation

Mlotshwa said initially migration in Zimbabwe was enforced physically by the colonial government that removed black people from their fertile ancestral lands to unproductive farming areas.

As a result men from Matabeleland South migrated to South Africa in droves to work on gold mines in the Witwatersrand for them to be able to continue providing for their families.

Colonial laws such as the Land Apportionment Act of 1930 discouraged many indigenous people, including those in Matabeleland South, from engaging in agriculture production and forced them into the wage labour market, including migrating to South Africa.

July Moyo, who was the Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare at the time of the investigation, acknowledged the link between migration and climate change, which he said had become a major subject of debate on international platforms.

“We have had international conferences discussing this issue,” said Moyo, who was moved to the Energy and Power Development portfolio this month.

“Actually, last of (2023), I attended conferences in Greece and Geneva where we were talking about the relationship between climate change and migration.”

Zimbabwe chaired the second Conference of Parties (COP) in 1996 and the minister said at the time the issues were not being taken seriously.

“If you see how water is rising in the seas and some of the islands are now sinking, displacing a number of people who end up migrating, then you notice that indeed climate change can induce migration,” Moyo added.

Academics, Janna Frischen, Isabel Meza, Daniel Rupp, Katharina Wietler and Michael Hagenlocher in their book titled DroughT Risk to Agricultural Systems in Zimbabwe: A Spatial Analysis of Hazard, Exposure and Vulnerability published in 2020 say Zimbabwe is one of the countries that are seeing an increase in the frequency of droughts as a result of climate change.

The droughts have led to acute water shortages, declining yields, and periods of food insecurity at a time the economy has been on a downward spiral.

Droughts now more frequent

Since independence Zimbabwe has witnessed droughts during the 1991/1992, 1994/1995, 2002/2003, 2015/2016, 2018/2019 and 2023/2024 agriculture seasons with Matabeleland being the hardest hit region

Various publications such as IOM, Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and ZimStat gleaned as part of this investigation noted that migrant flows have become a major coping strategy for many people in Matabeleland South in response to climatic shocks.

In its Zimbabwe 2022 Population and Housing Census Report, ZimStat said:

“Matabeleland South Province had the largest proportion: 33 percent, of households that experienced loss of members through emigration.”

Matabeleland North and Masvingo provinces experienced losses of 24.2 percent and 22.7 percent respectively.

https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/Demography/Census/2022_PHC_Report_27012023_Final.pdf

According to the ZimStat 2022 census report and IOM situational reports published throughout 2024, most Zimbabweans are leaving the country in pursuit of elusive economic opportunities at home.

The Matabeleland South Report of the Zimbabwe Livelihoods Assessment Committee (ZimLAC) 2024 Rural Livelihoods Assessment said unemployment was the major challenge facing the youth in the province at 79.4 percent followed by substance abuse (67.6 percent).

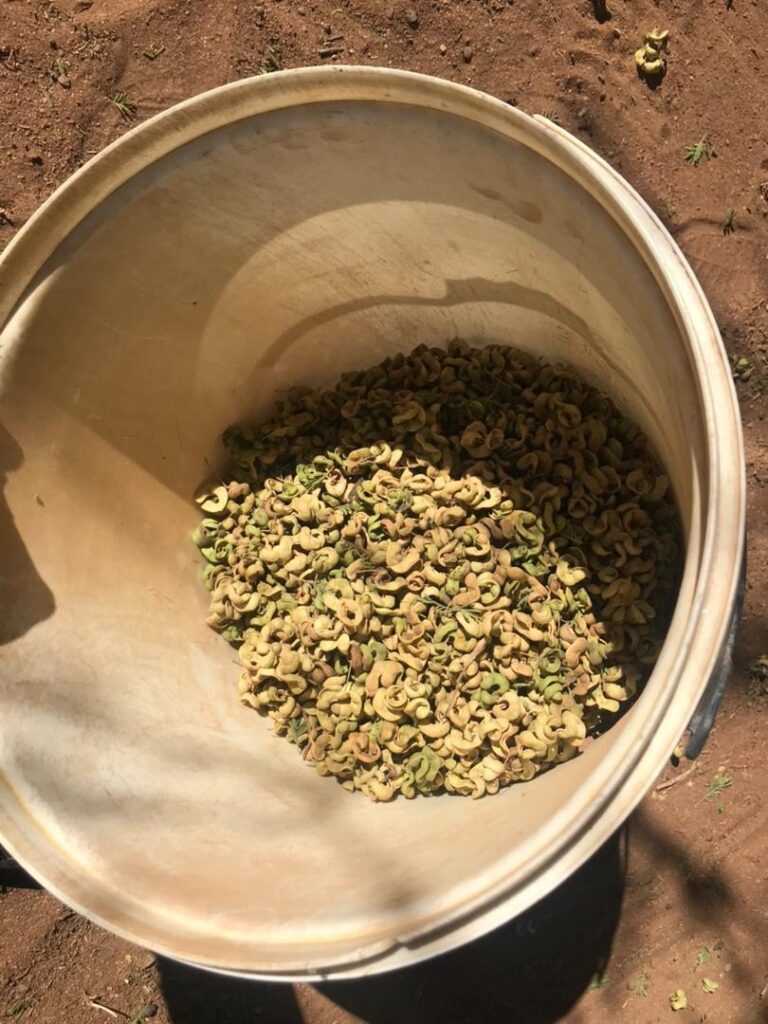

It also noted agriculture has become unviable because of changes in climate with about 60.1 percent of households not owning cattle and 25 percent without goats.

About 92 percent of the communities indicated that pastures were often inadequate and of poor quality.

https://www.fnc.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Matabeleland-South-RLA-2024-Report.pdf

Andile Nkomo (19) from Empandeni in Mangwe District said most of her peers from the village left for South Africa and Botswana soon after finishing school because frequent droughts made survival difficult.

“This was another very difficult year because of the drought,” Nkomo told CITE.

“It does not matter how much effort you put into tilling the land, you reap nothing.

“A lot of people are moving to other countries because of the drought.

“From my family everyone has crossed to Botswana or South Africa even those that don’t have passports.”

Sakhile Tshuma from Madabe village near Plumtree, but is based in Johannesburg, said she is forced to send groceries back home every month because her family has no other source of food due to frequent droughts.

“They have not harvested anything meaningful for the past three seasons and they have lost a lot of livestock due to droughts,” Tshuma said.

“I have to make sure I send food home every month for my children and siblings.

“The situation is now different from when we were growing up where my father would sell his cattle to raise money for school fees and food was mainly from subsistence farming.”

Child headed families

Makhadi Moyo, councillor for Ward 16 in Bulilima, said droughts were to blame for the high number of young people leaving her area to countries such as Botswana and South Africa where there were better standards of living.

“We have a lot of child-headed families because the parents or guardians have moved to other countries to raise money for food,” Moyo said.

“Food shortages are our biggest challenge and the government has been very slow in providing food aid to hungry families.”

Winani Ncube, a traditional leader from Village 23 also in Bulilima’s Ward 23, said hunger was taking a toll on his subjects.

Ncube said the cycle of poverty drove many people into desperation, which forced young people to migrate to other countries in numbers.

“I settled here in 1986 coming from Ndolwane (in Plumtree),” he said.

“I then became the village head and I know the struggles that people are facing.

“It’s tough because people are starving. We even sell the feed for our livestock to raise money or exchange it for food.”

Reena Ghelani, the UN assistant secretary general and climate crisis coordinator, early this year said Zimbabwe and other southern African countries were seeing the “massive impact of the climate crisis.”

Ghelani said there was a need for urgent investment in communities to help them adapt to climate change.

Migration as coping mechanism

IOM Zimbabwe spokesperson Fadzai Nyamande-Pangeti said people often turn to migration as a coping mechanism when their livelihoods are threatened.

“Currently, we lack precise data on the number of migrants who have relocated due to climate-induced phenomena like droughts,” Nyamande Pangeti said.

“The International Organisation for Migration is conducting a study to gain a clearer understanding of mobility patterns and trends related to drought.

“People often turn to migration as a coping mechanism when their livelihood is affected by shocks.

“In the case of drought, its effects on households and households’ incomes are likely to lead people to move from an area of extreme stress to one which they deem habitable and with favourable opportunities.”

She said other climate related challenges include heavy rains that cause flooding and significant damage to the environment.

In the last few years, Zimbabwe has been hit by a number of cyclones with Cyclone Idai of 2020 being the most devastating as it killed 634 people and displaced thousands others.

IOM said decreasing rainfall was forcing entire families in Zimbabwe’s rural areas to migrate to urban areas or neighbouring countries.

“As livelihoods in rural areas decline due to decreasing rainfall, families are more likely to migrate,” Nyamande-Pangeti said.

“However, in most cases, men are the ones who are moving, leaving women and children behind.

“This trend leaves women to manage the day-to-day impacts of climate change, such as reduced crop yields and water shortages, while also taking on the responsibilities of running the household in the absence of the men.”

UNHCR says climate change increases the risks of extreme weather events – like storms, floods, wildfires, heatwaves and droughts – making them more unpredictable, frequent and intense.

The agency added that at the same time, rising sea levels, droughts and drastic changes in rainfall pattern as a result of warmer temperatures can destroy crops and kill livestock, threatening livelihoods and exacerbating food insecurity- all which can force people to migrate.