By Bafana Ndutywa

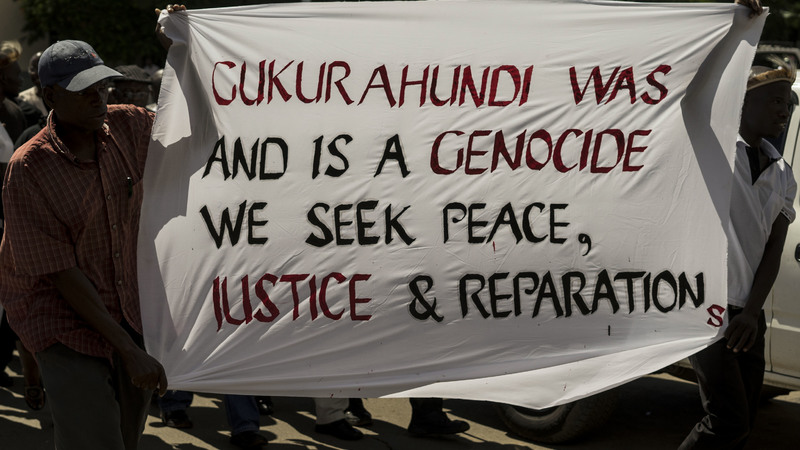

The Zimbabwean government’s cynical attitude towards victims of the Gukurahundi genocide was brought sharply into focus by three media reports last week.

The first one is the report which made headlines throughout the world. As first reported by the UK’s Guardian on 12 May 2022, Zimbabwe harboured and shielded perhaps the most wanted genocidaire from the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, Protais Mpiranya. Unlike his hundreds of thousands of victims, most of whom never received decent burials, Mpiranya was found buried at a cemetery in Harare after dying from natural causes. According to a UN forensic investigation team, his relatives travelled from across the globe to give him a respectable send-off in Harare, where he had lived under a false name – most likely with the blessings of the authorities.

The second story was on the response of the Zimbabwean government, smarting from the avalanche of criticism after the UN team forensically detailed how it recruited and then brought Mpiranya to Harare. Zimbabwe suddenly declared willingness to hand over another notorious genocidaire that it has protected for decades, the former Ethiopian dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam. Mengistu has been living in the country for at least from 1991, enjoying the kind of protection and luxurious existence that Zimbabweans can only dream of. Zimbabwe’s minister of foreign affairs, Frederick Shava, told the Voice of America’s Studio 7 that Harare would surrender Mengistu to Ethiopia if that country made a request. It was noteworthy that the foreign affairs minister allowed Studio 7 an audience, given that they are constantly labelled enemy media and the government normally ignores them unless it wishes to reach an international audience.

The third story was buried within the Newsday of 21 May 2022 and did not make international news. But it was equally significant. According to Newsday, the Mnangagwa administration intends to close the chapter on the Gukurahundi genocide before the general elections next year. Speaking during an induction workshop for commissioners of the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC), Zimbabwe’s speaker of parliament, Jacob Mudenda, implored the commission to bring closure to the Gukurahundi ‘subject’ before next year’s elections.

Mpiranya’s story is sad and frustrating not only with regard to his Tutsi victims, but even more so to Gukurahundi victims across Zimbabwe and beyond. For many of us who went through the horrors of Gukurahundi as children, the story of how Rwanda dealt with the horrors of the genocide against the Tutsi makes us wonder how things could have been if a truly responsible government had emerged from the unity accord of December 1987.

Instead of dealing with the horrors, it caused, allowing victims and survivors in Matebeleland and in parts of the Midlands to find closure, Zimbabwe’s rulers instead found the time and the resources to harbour a man who was at the centre of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. Nothing explains the psychology of our rulers better. During the late 1990s, while much of the world engaged in efforts to help Rwanda deal with the horrors of its past, Zimbabwe’s army was in the trenches in the DRC with men who had committed indescribable crimes. It provided these monsters sanctuary and God knows what else.

I first learnt of Zimbabwe harbouring Mengistu in the late 1990s. It was after I read a story in which Zimbabwean security personnel guarding the former dictator’s home in Harare were said to have repelled an attempt by an Ethiopian crack team to either kill or apprehend the fiend. After the three disturbing reports from last week, I revisited stories from the 1990s quoting the US Embassy in Harare as having admitted that it facilitated Mengistu’s flight from Addis to Zimbabwe. The excuse was that it was important to get a ‘safe haven’ for the genocidal dictator so that Ethiopia could find peace. That no institution, including Zimbabwe’s parliament, tried to make our leaders account for Mengistu’s presence in this country underlines the incapacitation that bedevils our institutions.

Mudenda’s insensitive comments were ill-timed coming in a week when Zimbabwe was under international scrutiny for harbouring one of the world’s most wanted mass murderers and actively thwarting efforts to find and apprehend him. The speaker of our parliament reminded survivors of the Gukurahundi genocide what seems to have always been government’s position — that they are merely pawns in his party’s game of retaining power at all costs.

Rwanda has taught the world, particularly Africa, that it is possible to help survivors, their communities and an entire nation to deal with the indescribable nightmare of a genocide. But to do so, communities, survivors and victims’ families themselves must be central to processes set up to deal with their horrors. Whatever criticism can be made about Rwanda’s gacaca courts, the philosophy behind them was that healing could only be achieved when communities actively participated in processes meant to facilitate transition through dialogue and administering of justice. Further – and this can never be overemphasised – those responsible must be held to account for their actions. It is for this reason that Rwanda has relentlessly pursued the perpetrators of the genocide against the Tutsi.

But another important lesson from Rwanda is that in order to deal with the aftermath of a genocide, a country needs international assistance especially from the United Nations, which has the experience as well as the capacity to deal with crimes of that nature and degree. Local mechanisms, such as South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, can be effective frameworks for helping a country deal with a painful past, but they can only work if there is an enabling political environment. Local efforts also require international cooperation, not only in the form of much needed technical assistance, but also pressure on state bureaucrats and leaders who may have been involved in the crimes and may therefore thwart any serious processes in order to protect themselves.

In Zimbabwe, the state under the government of former president Robert Mugabe and now under Emmerson Mnangagwa has been the biggest obstacle to Matebeleland communities’ attempts to deal with the Gukurahundi genocide. Not content with refusing to acknowledge their role in the genocide, Mugabe and Mnangagwa’s governments effectively criminalised any efforts to resolve the Gukurahundi.

For Mugabe, the people of Matebeleland had to let bygones be bygones. Gukurahundi was, after all, just a fleeting ‘moment of madness’, people needed to move on. Matebeleland needed to embrace the unity between Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo by abandoning any hope of justice or closure for Gukurahundi.

But the current regime has been worse in this regard. After decades of being criminalised even for mentioning the word Gukurahundi, Mnangagwa’s regime made people believe that his government was ushering in a new era – the ‘new dispensation’ as it called it. Henceforth, or so it was said, communities and individuals who experienced the genocide would be free to express themselves and to ask for assistance from the state. Communities across the length and breadth of Matebeleland held their collective breath thinking that finally, they will be able to find the closure they have craved and cherished for decades.

Among their demands – and this needs to be emphasised – communities wanted to get assistance to exhume and rebury their dead with dignity. They wanted to get much-needed documents such as national IDs and birth certificates for those who have so far failed to do so as a result of the genocide. They also wanted those who perpetrated the genocide to be held to account. Some also wanted reparations, which could take many different forms depending on the demands of individuals and communities, while for others closure could not be found at all unless they received assistance to find the remains of their loved ones and to know how they met their fate. Above all, they have demanded an official acknowledgment of the role of Zimbabwe’s military and other security services, followed by an unequivocal apology.

These modest demands are important to reconsider in the context of Mudenda’s insensitivity. The NPRC could deliver some if not all of the expectations of Gukurahundi victims, if it operated independently and if victims of Gukurahundi had some power in the selection of at least some of the commissioners. Mudenda’s patronising talk towards NPRC commissioners is testament to the ruling party’s attitude that the commission should answer to the demands of the government, and not to the concerned communities. It is more concerning that Mudenda’s lack of empathy cannot be regarded as an unfortunate slip. Barely a year ago, the NPRC’s self-appointed spokesman, Obert Gutu dismissed the Gukurahundi genocide as ‘a small, tiny fraction’ of the NPRC’s mandate. It says a lot about the NPRC and Zimbabwe’s attitude towards the genocide that a man like Gutu could even sit on the commission.

Since the new administration came to power, the NPRC has not been able to articulate any clear programme for dealing with Gukurahundi. Instead, the government has shifted between ordering the NPRC to deal with the genocide, and declaring chiefs to be the institutions to perform same role. Effectively, as Mudenda’s remarks also revealed, the NPRC can deal with the Gukurahundi but only in the manner and at the pace which satisfies the ruling government and the president.

The role of chiefs is even more frustrating. Through its endless pronouncements, the government has decreed that communities cannot do anything about Gukurahundi without permission from their local chief. Indeed, many civic activists have noted that most chiefs in Matebeleland are the obstacles to any serious attempts to deal with Gukurahundi. While it has to be said that some chiefs have bravely assisted their subjects, many more are not forthcoming because of fear of an overarching state. This is because just like the NPRC, our chiefs are also servants of our rulers. Often, they act as if they are extensions of the executive in their jurisdictions. Through resources such as stipends, vehicles, recommendations to various boards of state companies and dangling the hope of some being seconded to the senate, the government has effectively emasculated many chiefs. Without any resources outside those extended to them through the executive’s benevolence, the chiefs understand too well that anything that goes against the ruling government’s wishes may threaten their own survival.

The government has also dangled the hope of resolving Gukurahundi to desperate communities, while at the same time indicating through its rhetoric that there has been no change from Mugabe’s approach. We only have to examine the language that the president himself has employed against his opponents in the recent past, including against so-called Mthwakazi separatists. The term Mthwakazi, which carries deeper meaning than politics for Ndebele citizens of Zimbabwe, has also been effectively criminalised.

Just a couple of months ago, President Mnangagwa was in the news threatening the Mthwakazi Republican Party (MRP) and its president Mqondisi Moyo for what he called MRP attempts to divide Zimbabwe into small states. Two issues stand out from the president’s utterances at the rally in the town of Chitungwiza. The first one is his chilling threat that Moyo ‘will have shorter days to live’ on this earth, if he continued to call for a separate state. This threat needs to be contextualised within the vocabulary that many of Zimbabwe’s leaders used against Ndebele victims of the Gukurahundi in the 1980s. In March last year, a video circulated on social media networks of the president warning rural Zimbabweans that they should clean their homes and rid themselves of ‘mapete’ (which is Shona for cockroaches). He went further to threaten that village inspectors would be deployed to go around homesteads and search for ‘mapete’. Anyone familiar with the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda – of which the president and his administration surely are – knows well how this imagery was used by Hutu supremacists like Mpiranya to describe their victims.

The second issue is the failure to recognise that calls for a separate state, and indeed ethnicisation of politics in Matebeleland is a response to the continuation of Gukurahundi in the form of the marginalisation of the region and its people post the genocide. So much can be said about this.

At any rate, any process that refuses to meet survivors’ and victims’ families’ demands concerning the Gukurahundi genocide threatens not just Matebeleland but also Zimbabwe’s interests as a whole. Saying the Gukurahundi genocide was a moment of madness is not enough and does not adequately deal with a tragic and sad period of Zimbabwe’s history.

*Ndutywa is a developmental worker.