As Bulawayo continues to grapple with severe water shortages, the local authority has once again proposed recycling water from the long-abandoned Khami Dam, a plan that has sparked renewed resistance and criticism from residents and civic groups.

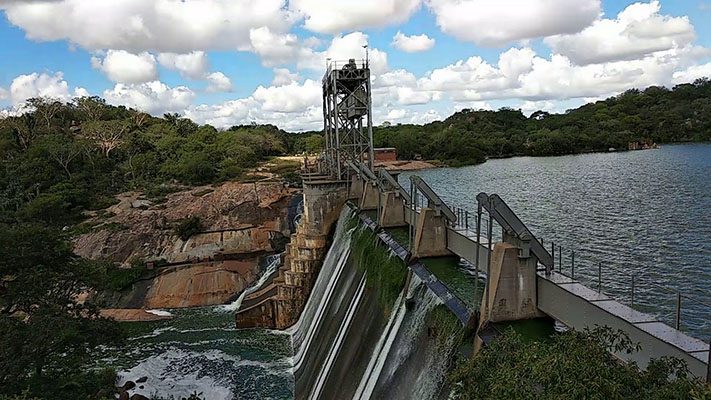

Built in 1928 and decommissioned in 1988 due to contamination, Khami Dam’s stagnant waters have since turned green and thick with algae and sewage discharge. Despite assurances of safety from city officials, residents remain deeply skeptical.

“There is an old, standing position of the residents that they do not want Khami Dam water,” said Winos Dube, chairperson of the Bulawayo Residents Association (BURA).

“According to past debates, Khami Dam is one of the most contaminated water sources in Bulawayo, and people are mentally embedded with the belief that it’s unsafe.”

Dube warned that the city council must engage widely with residents before proceeding, stressing that community trust must be earned through transparency and information-sharing.

“Convincing people will not be easy. People will not like this idea. There might even be issues of classism because this water will mostly serve residents from the high-density suburbs,” he said.

“They may argue that their concerns are not considered compared to those in low-density areas who may not be affected by Khami water at all.”

Khumbulani Maphosa, Coordinator of Voices for Water, a civic group promoting water rights, said the resistance stems from issues of trust and dignity, not just health concerns.

“The whole debate about the use of Khami Dam water in Bulawayo has centred on sentimental issues,” Maphosa told CITEZW.

“There is a lack of trust in the system’s ability to recycle water adequately, especially when we sometimes have problems with our ordinary dam water.”

He added that residents’ resistance is rooted in emotional and historical fears rather than proven scientific evidence.

“There is also the issue of the pride of the people, they have set their own standards that they will not drink water from the toilet, even if it’s recycled,” he said.

“It has not been an argument backed by empirical evidence of the local authority’s inability to recycle water. But these reasons are critical, because we’ve been colonised and made to think in terms of global standards.”

“If proper development and service delivery are to be achieved, they must respond to the sentimental issues of the people, how they value certain things. That indigenous knowledge system of attachment to a service is critical.”

Maphosa emphasised that acceptability among residents will be key to the success of any water recycling plan.

“The concept of acceptability is critical in water service delivery,” he said.

“The water can be recycled to the highest standards, but if people don’t accept it because it’s from sewer water, then there’s a serious problem.”

He suggested that the council could consider mixing recycled Khami water with cleaner water from other dams to build public confidence.

“If they recycle, they shouldn’t provide it as is, but mix it with other water sources. That could build some confidence among residents.”

However, Maphosa also said the move signals failure by both government and council to find lasting solutions to Bulawayo’s chronic water crisis.

Water rights campaigner Donald Khumalo echoed these concerns, urging the council to prioritise transparency and independent testing to rebuild public trust.

“A lot of things need to be considered when talking about Khami water. The council needs to be as transparent as possible to win the trust of the people,” Khumalo said.

“They must engage people extensively because trust in the quality of Khami Dam water is very low. People have been resisting that water for years, and convincing them otherwise may be difficult.”

He stressed the importance of allowing residents and stakeholders to conduct their own tests to validate the city’s findings.

“The council needs to engage experts to conduct tests transparently, with robust quality control. Transparency is what’s important,” he said.

“The truth is we really need water in Bulawayo, but people also need to be assured of their safety.”

According to the latest Bulawayo City Council minutes, Town Clerk Christopher Dube acknowledged residents’ concerns, emphasising the need for community engagement and education on water safety.

Meanwhile, Engineer Sikhumbuzo Ncube, the city’s Director of Water and Sanitation, assured that tests show Khami water is clean and safe for recycling and potential use.

The Joint Portfolio Committee on Local Government and Sustainable Development Goals has given the council until the end of the year to consider tapping into Khami Dam as an alternative water source.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today

Leave a comment