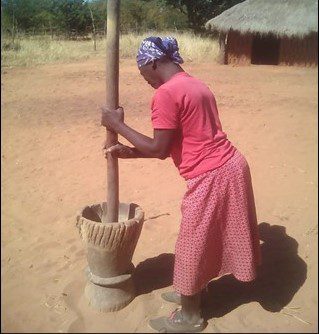

“I am the first to wake up in the morning ahead of all household members and am the last to sleep in the evening because I have to fetch water, firewood, cook, bath children, tidy the yard and a whole lot of other household chores,” says Belitha Mumpande, from Binga in Matabeleland North.

Mumpande is a 65-year-old woman and second wife to Petro Munenge. Belitha has been in this marriage for 34 years. She is the ever-toiling, untiring and hard-working woman in her household as she is expected to carry out all her household duties without any disgruntlement.

For her, doing these duties is part of what she perceives as impressing her husband. She has no thoughts of having any of these duties redistributed to any of her household members, let alone her quasi-king husband. In other words, for her it is not a ‘life burden’ at all but a ‘life assignment’.

Olga Mtetwa an Administrative Officer in the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, Community, Small and Medium Enterprises Development confirmed that women in Binga are in a socio-economic development quandary given their burdens which are deeply rooted in unpaid care work.

She alluded to the women’s ‘24-hour diary’, a tool that is used by the Ministry to analyse how women spend their time in households. A tool that also brings out how women toil all round the clock at household level in such a way that deprives them of time to meaningfully participate in development activities.

“Belitha’s situation is not unique to her and reflects that society does not recognise work done by women at household level as real work, as such, but a close analysis of time diaries of Binga women also shows that 75% of women in Binga have no time to rest or spare for developmental activities,” said Mtetwa.

“If ever they get an opportunity to be involved in development activities, their participation is barely significant.”

Mtetwa explains further: “Limited participation of women in developmental activities and leadership structures is deeply rooted in unpaid care work. In the case of Binga, only 4% of councillors are women, whilst 6% are village heads with no women being chiefs.”

More so, for Belitha, it is a quasi-right, natural and God-set phenomenon for women to carry out household duties which span from fetching water to serving food to her husband and children.

She even perceives it as a taboo, for her to even think or suggest delegating the household duties she calls “women’s ‘work’. She owns the duties so that without them she believes she would be an incomplete woman.

She does not perceive unpaid care work as a barrier to her meaningful participation in developmental activities.

“Oh! It is unheard of to see my husband fetching water or cooking while I am around, certainly society would suspect that I may have used juju on him,” Said Belitha.

“My in-laws and kinsman would not smile at such a thing nor condone it.”

Belitha is a God-fearing Christian whose perception of care work is informed by the biblical call for women to be submissive to their husbands.

Therefore, she perceives care work as part of being submissive and loyal to her husband. During our interview, she indicates that even the women’s association at her church emphasises upholding traits of submissiveness and loyalty.

“The Bible itself clearly tells us in Ephesians 5: 22 that wives should submit to their husbands in the same way they do to the Lord,” said Belitha with confidence and surety.

“I can therefore not hesitate to do everything to show my submissiveness and loyalty to my husband. One way of showing this submissiveness is through serving my husband diligently through care work at household level”.

She reiterated that she has no thoughts or intentions of changing the current set-up which she has lived with for 34 years.

When asked, her husband Petro, echoed the same sentiments with regards to care work duties carried out by women. Petro rather perceives the work of women at household level as repayment for lobola or dowry.

Petro’s perception is one among a myriad of factors that perpetuate the existence of unfair distribution of household caregiving responsibilities.

“When we marry these women, we pay lobola, therefore whatever they then do at household level is mere repayment of the cattle, goats and money paid to in-laws as dowry,” said Munenge.

“Thinking or suggesting redistribution of care work done by women is un-African and a daring act,” emphasised Petro.

The District head for Women Affairs in Binga, Richard Mudimba had a different view of this. He perceives care work as a perpetuated retrogressive setback to women’s participation in development.

“As long as we leave mammoth household chores to women only, their participation in developmental and decision-making processes will remain deplorable.”

“Men are unwilling to change this set up because it benefits them and rural women are on the other hand caught in between openly revolting against this,” said Mudimba.

“As a ministry, we are doing all we can to mainstream gender and raise awareness to rural women with regards to their burden of household chores.”

Mudimba also highlighted that if care work can be redistributed and reduced at a household level, then it may go a long way in creating opportunities for women to partake in economic activities especially in Binga district where male dominance prevails.

Pastor Jumpule Kabanga of Assemblies of God in Binga also echoed the need for redistribution of household chores to allow women to partake in key developmental activities. He, however, emphasised the rationalisation of the redistribution to balance the biblical dictates and women’s rights.