By Paul Hubbard, Independent Researcher, Bulawayo

Bulawayo’s Athlone Cemetery is the oldest formal graveyard in the modern city, being established in December 1893 in the vicinity of what was known as White Man’s Camp. There are many significant personalities buried there. Few regularly excite as regular attention as two BaLozi graves buried in an area once reserved for the Anglican Church and later re-designated for Bulawayo’s Chinese population in a small section, bordering Athlone Avenue, now reserved for BaLozi royalty.

The BaLozi people and their royal leaders had several connections to Bulawayo before the 1940s.(For background on the history of the BaLozi people I suggest Bull 1972; Clay 1968; Hogan 2014; Turner 1952). Many came to work on the railways, farms and mines in and near the town and also travelled though on their way to elsewhere in the region. Barotseland was treated as a “labour reserve” by the colonial authorities well into the 1940s (Hogan 2014). Most famously perhaps was the visit of Litunga Lubosi Lewanika in 1902 who stayed in the original Hotel Cecil (Fife Street & 3rd Avenue) on his way home from attending the coronation of the English King Edward VII.

Prince Mbanga Lewanika (1890-1922) was a son of the famous King Lewanika and a brother to Paramount Chief Yeta III. He died of meningitis in Bulawayo’s Memorial Hospital on 18 October 1922. He had been travelling home from Zonnebloom College (at that time, a Training College for ‘Coloured ’students, near Cape Town) where he had been studying but his illness became so severe he could not continue on the train. His funeral was attended by members of the Royal Batorse household as well as at least 50 BaLozi people resident in Bulawayo at the time. Even though he was a baptised Christian, some traditional practices were followed at his funeral including lining the grave and wrapping the coffin in reed mats, supplied by the Native Department. A number of people spoke of the prince at his funeral on 20 October after which the area around the grave was surrounded by a high fence of reed mats as was the custom of the time. This adherence to BaLozi funeral customs explains why the graves are separated from the rest of the cemetery as royalty could not be buried amongst strangers nor commoners. The Rhodesian Native Department, represent by N.D.H. Spicer, knew of and respected these customs and encouraged the Bulawayo Town Council to do the same.

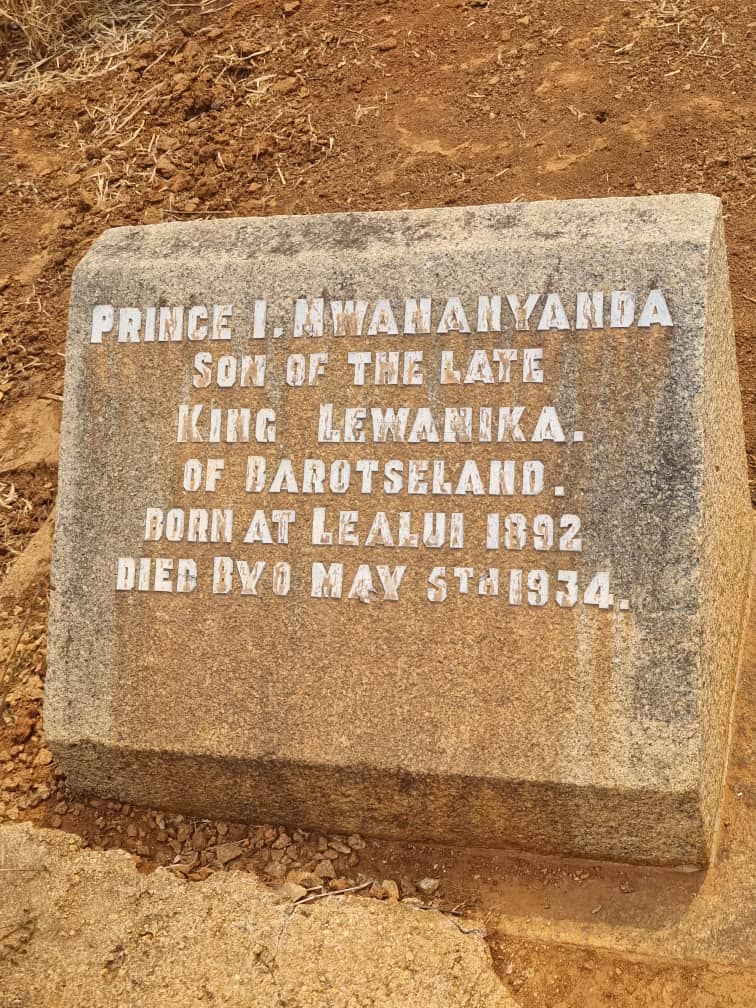

On 5 May 1934, Mbanga’s brother, Prince Imbowa Mwananyanda Lewanika (1892-1934) died and was shortly afterwards buried beside him. He had also passed away in Memorial Hospital, at the age of 42, surrounded by many BaLozi who were resident in Bulawayo at the time. Ill health had forced him to resign as head teacher of the National Barotse school in Mongu, located a few kilometres from Lealui, the BaLozi dry season capital. What he was doing in Bulawayo at the time of his death remains unclear, but I would venture to suggest he was in Bulawayo specifically to receive medical treatment in Memorial Hospital, the best hospital in the Central African region at that time and easily accessible via train from western Zambia. His funeral cortege included many motor vehicles and over 200 mourners who first attended a service at the African Methodist Church in Makokoba followed by a procession to the cemetery.

In an interview in The Chronicle in 1981, John Jamieson and Elizabeth Alfred claimed to be related to Mbanga Lewanika. They said he was the brother to their mother, Tinta Lewanika, a child of the Lozi king. She had been captured during an Ndebele raid in the late 1880s or early 1890s and went on to live with James Jamieson in the Solusi area. They married in 1929 and she died in 1937 and was buried on Roseburn Farm, near Solusi Mission. The Jamieson family have visited the graves many times according to recent posts on social media; they continue to hold them in reverence.

The graves have been reported to the Zambian Embassy in Harare multiple times. It would be appropriate and just to see the fence restored around the area and annual maintenance done on and around the graves. The responsibility could be shared among the Bulawayo City Council with funding from the Barotse Council and/or Zambian Government. There is local precedent for this suggestion as the graves of Zimbabwean casualties in Zambia and Mozambique are cared for in a similar manner in Zambia and Mozambique (e.g. Zimbabwe Independent 06 March 2024; Sunday Mail 19 April 2015). As an aside, I have personally cleared the grass, weeds and litter from the graves multiple times over the 20 years or so since I first saw them and will continue to do so as circumstances allow. It would be wonderful to see more care being given to the cemetery in general.

References

Published Materials

Bull, M.M. 1972. Lewanika’s Achievement. The Journal of African History 13 (3): 463-472.

Clay, G. 1968. Your Friend Lewanika. Litunga of Barotseland 1842-1916. London: Chatto & Windus.

Hogan, J. 2014. ‘What Then Happened To Our Eden?’: The Long History of Lozi Secessionism, 1890–2013. Journal of Southern African Studies 40 (5): 907-924.

Turner, V.W. 1952. The Lozi Peoples of North-Western Rhodesia. London: International African Institute.

Newspapers

The Chronicle, 21 October 1922

The Chronicle, 8 May 1934

The Chronicle, 12 September 1981

The Chronicle, 17 September 1981

The Chronicle, 19 September 1981

Webpages