Twenty-six girls dropped out of school due to pregnancy and early marriage in the last quarter of the year in Bulawayo, exposing the persistent social and structural barriers undermining efforts to keep children, particularly girls, in schools.

This emerged from a School Dropout Analysis presented by Bulawayo National AIDS Council (NAC) Programmes Officer, Douglas Moyo during a Bulawayo Programmes Update to the media, where he warned that continued prevention efforts were critical if the city was to break the cycle linking school dropout, teenage pregnancy, poverty and HIV vulnerability.

Moyo revealed that in the third quarter of 2025, a total of 96 learners dropped out of school, with 89 from secondary schools and seven from primary schools.

While the figures show a positive downward trend across three consecutive quarters, he cautioned that the reasons behind the dropouts remained troubling and largely preventable.

“We are seeing a positive trend in that there has been a continuous decline in dropouts across the three quarters,” Moyo said.

“The high figures we recorded in the first quarter were largely attributed to risky behaviour during the December school break of the previous year.”

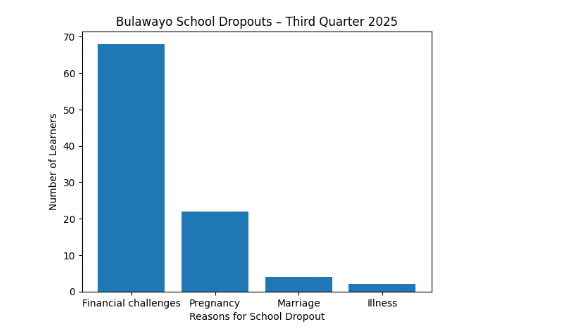

According to NAC data, 68 learners dropped out due to financial challenges, 22 girls left school because of pregnancy, four girls dropped out after getting married, while two learners dropped out due to illness.

“Whose children are we talking about that are dropping out of school due to pregnancy? Whose children are we talking about? When we have men in this room, when we have men in our homes, when we have uncles in our homes, but we have children dropping out due to pregnancy. But if you look at the reasons why these children dropped out of school, none of them would justify a child dropping out of school,” Moyo said.

He described the 68 cases linked to financial hardship as particularly painful, especially in a context where families are extended and can pull resources.

“If we are a society that is supportive to each other, should a child drop out of school because of fees?” he asked.

“Especially at primary level, how much are the fees? It’s about US$100 per term. It’s a sad situation.”

Moyo said the figures raised serious questions about sustainability, especially for children previously supported by donor-funded programmes.

“Yes, one can argue that some of these children were supported by donors and the donors have stopped,” he said. “But going forward, what are we saying about sustaining our children in school?”

While 22 girls dropping out due to pregnancy may appear low on paper, Moyo warned that the number does not reflect the true scale of teenage pregnancy in Bulawayo.

“I am saying this figure is low because this is data from the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education,” said the NAC official.

“If you go to the Ministry of Health and look at clinic statistics for pregnancies in the 10 to 24 age group, you will get very high figures.”

He explained that schools are not medically equipped to identify pregnancies and often only capture cases where girls remain in school while pregnant.

“Remember, policy now allows a child to continue schooling while pregnant, go and deliver, and come back,” Moyo said.

“So these are the few who remain visible within the school system.”

However, stigma and shame continue to push many girls out of school quietly.

“There are challenges, the shame, the stigmatisation,” he said.

“Parents end up removing children from the locality, from the school, because of stigma. So we still have a challenge there.”

Moyo challenged men to take responsibility for teenage pregnancies, describing them as a societal failure rather than a girls’ issue.

“I have challenged the men in our dialogues,” he said.

“Whose children are we talking about that are dropping out due to pregnancy? When we have men in this room, men in our homes, uncles in our homes yet children are dropping out.”

He warned that early disengagement from education at ages 10 to 19 had long-term implications.

“At that age, they are already not taking up services,” he said. “What happens when they graduate into adulthood? What is going to happen then?”

To address these vulnerabilities, NAC has rolled out several targeted prevention programmes across Bulawayo.

The Sista2Sista programme, implemented in four districts, has 40 active mentors and has reached 1 804 mentees, achieving 90.2 percent of its target. About 10 percent were referred for HIV testing services, with a 6.8 percent positivity rate.

Meanwhile, the Brotha2Brotha programme, implemented in three districts, reached 1 265 young men, 84 percent coverage, with 24 percent referred for HIV testing and zero percent positivity recorded.

“This shows that when young men are engaged consistently, outcomes can improve,” Moyo said.

In Bulawayo South, a modified DREAMS programme is supporting adolescent girls and young women, with 5 874 girls completing at least five primary combination prevention sessions, while 152 girls received school fee subsidies.

“This is a modified DREAMS because a full DREAMS package is very expensive,” Moyo explained. “It covers fees, uniforms, stationery, everything. It’s heavy, but it is very necessary in keeping children in school.”

The Peer-Led Programme, implemented in three districts, has 26 active mentors, reached 77 percent of its target, recorded a 12 percent HIV positivity rate, and achieved 100 percent linkage to care for positive cases.

Despite these interventions, Moyo said challenges persist among youth in tertiary institutions, where disrupted academic calendars and industrial attachments often break continuity in prevention programmes.

“We need to go beyond just giving information,” he said. “But continuity is a challenge when students are constantly moving between college and attachment.”

As Bulawayo records declining dropout figures, Moyo stressed that prevention efforts must not slow down.

“These statistics are speaking to us,” he said. “Our children are under our care. If they are dropping out, then as a society, we are failing them.”

Leave a comment