By Jeffrey Muvundusi

On any given day in Bulawayo’s bustling central business district, passers-by might encounter an unkempt Mthokozisi Mabuyane walking barefoot and weaving aimlessly through traffic.

Clad in tattered clothes and trailing a pungent odour, Mabuyane often draws the ire of motorists and strikes fear in pedestrians, who scatter at his approach.

The middle-aged man is not merely another troubled figure on the streets. He is part of a ballooning number of mentally-ill individuals in a city grappling with a growing public health crisis and lack of facilities to handle people battling mental disorders.

Originally from Dandanda in Lupane, Matabeleland North Province, Mabuyani once had a home and family.

Today, his presence on the streets tells a deeper story of abandonment, systemic neglect and a society ill-equipped to deal with a bludgeoning mental health crisis.

His mother, Nomthandazo Nyoni, sat on the edge of despair as she lamented the stigma and lack of access to medical facilities for her son.

“It’s never easy being a mother to someone with mental illness, especially in a society where people associate it with witchcraft, avenging spirits or demons,” she said, fighting back tears.

For the past two years, Nyoni has shuttled between hospitals and traditional healers, trying to bring her son back from the edge.

Her main stop has been Ingutsheni Central Hospital, Zimbabwe’s largest psychiatric institution located in Bulawayo, where Mabuyane has received treatment and temporary rehabilitation, but relapses have been frequent and severe.

“He has attempted suicide more times than I can count. He has been violent sometimes, making it hard for us to keep him at home,” Nyoni said.

“I am a single mother and this journey has drained me financially, emotionally and spiritually.”

Mentally-ill flood the streets

Nyoni’s story is harrowing, but not unique. Across Bulawayo, the sight of mentally ill individuals wandering the streets is becoming disturbingly common, a visible symptom of a hidden epidemic.

According to a 2023 Ministry of Health and Child Care report titled: Prevention and management of mental health conditions in Zimbabwe: A case for investment, the majority of mental health patients in the country often present with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, bipolar effective disorder (mania), epilepsy or the psychiatric complications of HIV.

The report said in psychiatric outpatient clinics and private practice, depression, substance dependence and anxiety disorders were frequently diagnosed.

While reliable statistics on drug use and its contribution to the surge in mental health disorders are not available in Zimbabwe, anecdotal evidence suggests a growing crisis.

The Zimbabwe Civil Liberties and Drug Network, said by 2021 drug abuse accounted for 60 percent of psychiatric admissions, with 80 percent of these involving young people aged between 16 and 25.

Drugs and substances that are commonly abused in Zimbabwe are marijuana, crystal meth, cough syrups and illicit alcohol.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says the prevalence of alcohol use disorders and alcohol dependence in Zimbabwe is 6.4 percent and 2.2 percent of the population, respectively.

These rates are significantly higher than the overall rates for the WHO Africa Region, which are between 3.7 percent and 1.3 percent, and this could explain Zimbabwe’s fast growing population of people with mental health disorders.

Investigations by CITE revealed that the rapidly rising number of people suffering from mental disorders is already overwhelming public health institutions in Bulawayo, leaving many without access to care and driving others like Mabuyane into the streets.

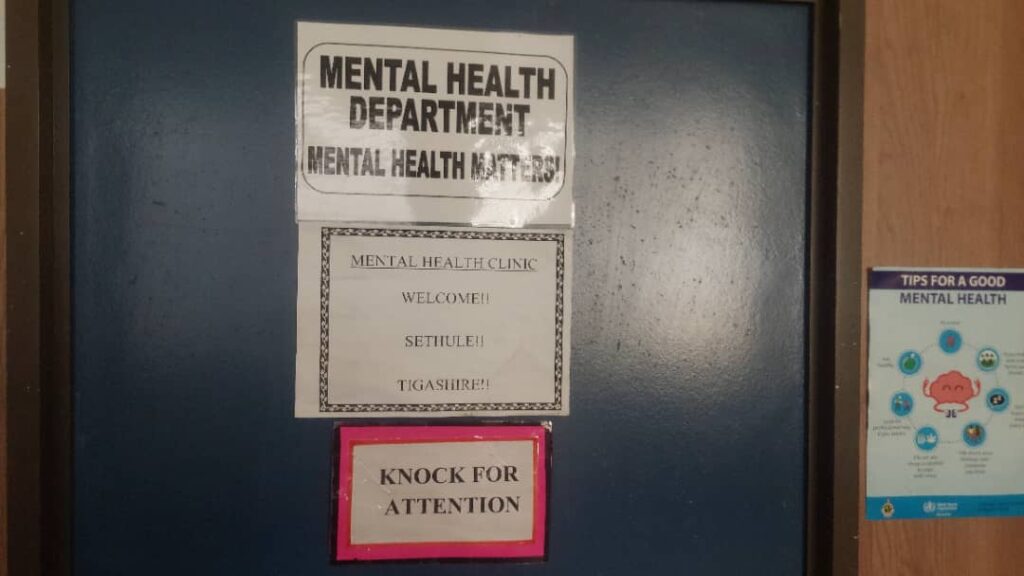

Besides Ingutsheni, in 2021 the government established mental health clinics at the United Bulawayo Hospitals (UBH) and Mpilo Central Hospital, which were coordinated through the provincial mental health office at the Mhlahlandlela Government Complex.

The centres, however, have made little impact with investigations showing that they were less active on the rehabilitation part as they largely handled acute cases before referring patients to Ingutsheni.

Ingutsheni overwhelmed

A visit to Ingutsheni during the investigation showed the depth of the problem, with infrastructure crying for maintenance while also overwhelmed by the number of patients.

The wards, both for males and females, were overcrowded. Patients ranged from teenagers to people in their 70s, with the majority aged between 20 and 40.

Dr Nemache Mawere, the Ingutsheni chief medical officer, painted a gloomy picture of the situation at the institution, saying the crisis was being exacerbated by the rising number of mental health patients whose conditions were linked to substance abuse.

The 708-bed facility accommodates over 600 patients across 14 wards, while its outpatient department handles about 2 400 cases every month.

Ingutsheni staff also takes care of Mlondolozi Prison, which houses around 400 patients with virtually no specialist psychiatric coverage.

“The demand for mental health services is really going up in Bulawayo,” Mawere said.

“Up to 70 percent of patients currently admitted to both the male and female psychiatric wards are battling substance-related mental health issues.

“As of August 11, there were about 605 patients at the hospital.

“For example, the Khumalo Ward has 160 patients, yet it is designed to hold only 98. It’s extremely overcrowded.

“The female ward is also overflowing, with 56 patients instead of the intended 46.”

In response to the escalating crisis, Ingutsheni has since introduced a mental health care programme (MHCP) aimed at decentralising mental health care across the city of nearly 700 000 people.

Mawere believes this is a model that could help Zimbabwe to manage the mental health crisis and solve the overcrowding at the few health institutions in the country.

“I would love to have that programme cascaded to all institutions so that people all over the country are aware of how to manage mental health problems, not just refer them to Ingutsheni and other central facilities,” he said.

“Everybody should be able to manage minor mental health problems in their own offices and in different locations around the country.”

Ingutsheni Hospital is also grappling with a severe shortage of psychiatrists, with only two doctors responsible for more than 650 inpatients and thousands of outpatients each month, underscoring the lack of prioritisation of mental health in the city.

Mpilo situation dire

At the Mpilo Hospital mental health clinic the situation is worse. The small, two-roomed facility located on the building’s ground floor is poorly equipped and lacks even basic tools such as a computer for data capture.

Investigations showed that the clinic handles no fewer than 50 patients a month, highlighting the increase in demand for mental health services.

The same pattern was observed across the Bulawayo City Council’s 20 clinics, which also refer mental health cases to Ingutsheni due to limited capacity.

This is despite the fact that Ingutsheni, originally designed to cater for long-term psychiatric patients, has been forced to also act as a rehabilitation centre due to decades of neglect and underinvestment in the country’s mental health care.

Council’s health department includes a gender, safety and health section, but mental health is still not prioritised.

The department’s wellness policy mainly targets council employees and does not sufficiently address broader public mental health needs. Council also does not have a specific budget to support mental health facilities.

The inadequate public mental health facilities has seen the mushrooming of private rehabilitation centres, especially for drug addicts but many of these centres are either under-resourced or unaffordable to most residents.

One such facility in the city is Mandipa Hope Rehabilitation Centre, which has a capacity for just 15 patients.

Carol Mashingaidze Tapfumaneyi, the Mandipa Hope Rehabilitation Centre director, said they offered holistic and professional care to individuals struggling with substance abuse and mental health disorders.

Their services include residential and outpatient treatment, detox supervision, trauma counselling, family therapy, relapse prevention, and aftercare support.

Mandipa Hope Rehabilitation Centre has no institutional backing and relies on resources from its founders and fees from clients, which means that a huge segment of the community cannot afford its services.

“Most people cannot afford rehabilitation as the costs are beyond many families’ reach,” Tapfumaneyi told CITE. “We strive to offer flexible payment plans and subsidised care where possible, but financial barriers remain significant.”

Sixty percent of the centre’s psychiatric patient admissions are for individuals aged between 16 and 25, who are battling substance abuse.

The centre, which has operations in Harare, Bulawayo, and Mutare receives nearly 8 000 calls for assistance each year, but can only assist a mere five percent of those in desperate need of help.

A grim picture

Another rehabilitation organisation, Active Youth Zimbabwe (AYZ), operating from a rented house in Nketa 7 high-density suburb, painted a grim picture of lack of mental health facilities in Bulawayo.

A tour of the house housing the centre showed that it was overwhelmed with 20 patients living on the premises while eight visit for rehabilitation from their homes every day. The patients had no structured treatment plans for professional supervision.

Romeo Matshazi, the AYZ director, said their clients included children as young as 10, who were addicted to drugs and other substances, showing the depth of the crisis.

Like Mandipa Hope Rehabilitation Centre, AYZ is underfunded and cannot cope with growing demand.

“So we have been relying on collaboration with the corporate sector to help us fight the scourge,” Matshazi said.

“Based on enquiries that we receive as an organisation, it shows that there is a seriously high demand for mental health services.

“At least 65 percent of the cases we are dealing with on a monthly basis are drug abuse based.

“But the age group we are dealing with mostly is those between 16 and 38 and per day on average we get between five and 10 inquiries.”

Investigations also revealed that most of the private rehabilitation centres do not meet the stringent requirements of the Health Professions Authority (HPA).

These include hiring qualified psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists and other licensed professionals costs that are often out of reach for smaller organisations.

As a result, some centres rely on external service providers, adding to operational complexity and expenses.

Another growing problem is a high relapse rate among patients with mental disorders, which in the long run stretches the already overwhelmed facilities when they resume treatment.

Psychiatrists said the large number of patients, who relapse, was largely attributed to the absence of proper rehabilitation facilities, easy access to drugs within communities and mounting socio-economic pressures.

Doctors, nurses also affected

Meanwhile, UBH chief medical officer William Busumani recently revealed that even some nurses and doctors were battling mental illness due to substance abuse.

“I want to inform you that we have our doctors and nurses who are admitted at Ingutsheni Hospital because of the drug scourge,” said Busumani during a drug and substance abuse resource mobilisation luncheon held at UBH early August.

“We have noted that these professionals become addicted to drugs while still at college before becoming professionals.”

Last year, President Emmerson Mnangagwa launched the Multi-Sectoral Drug and Substance Abuse Plan (2024- 2030) in response to the growing problem of drugs and substance abuse in Zimbabwe.

The plan was meant to strengthen enforcement of anti-drug laws and disrupt drug supply chains while also providing for prevention, treatment and rehabilitation services. Cabinet also gave its nod to the Drug and Substance Agency Bill that seeks to establish a specialised anti-drug agency.

Police have also launched several operations targeting drug barons and users, netting in hundreds of people, but the interventions have done little to stop the scourge.

Provinces are mobilising funds to help intensify programmes to tackle the crisis, including building rehabilitation centres for addicts and treatment centres for those with mental health disorders.

Bulawayo is seeking to raise US$280 000 under the same initiative. Police say the rising cases of mental health disorders are driving suicide cases in Bulawayo, particularly among young men.

Paying heavy price for neglect

The government admits that mental health is neglected in Zimbabwe and that this could be coming at a huge cost to the economy.

Dealing with mental health conditions cost the economy an estimated US$163.6 million in 2021, which was equivalent to 0.6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare said in the document titled; Prevention and Management of Mental Health Conditions in Zimbabwe: The Case for Investment.

Only five percent of this annual cost was actual expenditure on mental health services.

The remaining 95 percent was attributed to money lost to reduced workforce productivity due to premature death, disability, and poor performance at work.

It was also noted that many patients remained in psychiatric institutions far longer than necessary due to a lack of family support, which added worsened the financial burden on the state.

Community-based mental health services are scarce, and access to follow-up care or medication is limited or non-existent. These gaps often lead to relapse or re-admission, creating a vicious cycle that undermines recovery.

Mental health receives only 0.42 percent of Zimbabwe’s total annual health budget, which is equivalent to just US$0.13 per capita annually.

At the time the ministry predicted that by scaling up mental health services and interventions, Zimbabwe could save more than 11,000 lives and gain over 500000 healthy life years over the next two decades through reduced incidence, severity, and duration of mental illness.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today

Cite there should have been a full article on your facebook page now a days you are just typing a paragraph or two and one cannot view the full article like it used to be what is happening??

Surely the Chief Medical Officer for Ingutsheni should seek assistance from the World Health Organisation and other International NGOs like Rotary and Lions Club and Ministry of Health to come on board and there is no excuse whatsoever for the appalling state of the Hospital where a local couple offered to assist with the plumbing works

The Churches in the city the Ngos both local and international

Health organisations both local and international ngos could play a role

Then the airwaves, Radio Television stations and media could play an important role to encourage the residents of the city to refrain from substance abuse not sure if there is a helpline where residents can use if them or members of the family are involved in substance abuse

There is a Doctors without Borders an international NGO based in South Africa that possibly could assist as they deal with such issues as well

Very sad that no one doing anything

The councillor/ward that this institution falls under could be raising this concern at Council meetings but personally feel it needs the Members of Parliament and a collective group also to assist with this issue including the Bulawayo Progressive Residents Association most of the time they are dealing with issues about Water that is fine but other issues that are affecting the city need to be highlighted and brought to the forefront