Across Zimbabwe, early pregnancies continue to derail girls’ futures despite years of policy reform. Now, a community-driven campaign is redefining how villages protect their daughters.

*Sithulisile Dube (19), from Filabusi in Matabeleland South, did not write her Ordinary Level (O’ Level) examinations three years ago. She became pregnant at the beginning of the year and dropped out of school.

Although Zimbabwe’s laws have been relaxed to allow teenage mothers back in school, she has not returned.

“I know I could be living a better life if I had finished school and had progressed even to university but the stigma is a lot for a teenage mother,” she said. “I could not bear the pain of being ill-treated by other students at school and decided to stay at home. I could not even go to church because I was afraid that people would say I brought shame to my Catholic family.”

Her story mirrors that of countless other girls who, despite growing awareness about teenage pregnancy, find themselves leaving school and trading the dream of an education for the realities of early motherhood.

Sithulisile said, on reflection, she got pregnant because of a lack of knowledge on preventing pregnancy.

“I became sexually active at a young age, at 15,” she said. “I was impregnated by a 19-year-old. I did not know about safe sex and was sleeping without condoms.”

Another teenage mother, Roselyn Moyo (17) also from Filabusi said when she weans off her baby this year, she hopes to return to school next year. Roselyn is not afraid of any stigma attached to teenage motherhood because she said will continue with her studies in a school in another province.

“I will leave my child with my mother and will go to Tsholotsho in Matabeleland North to stay with relatives,” she said. It is important that I finish my schooling, get my O’Levels and try to go to college. I was not a bad student at all.”

O’Levels are the first public examination that any Zimbabwean child sits for and the certificate is the basis of all qualifications in the country. For many girls in Zimbabwe, pregnancy does not just interrupt school, it ends the dream of sitting for final exams, shutting them out of the formal job market and the promise of economic independence.

Teenage pregnancy in Zimbabwe: A growing problem

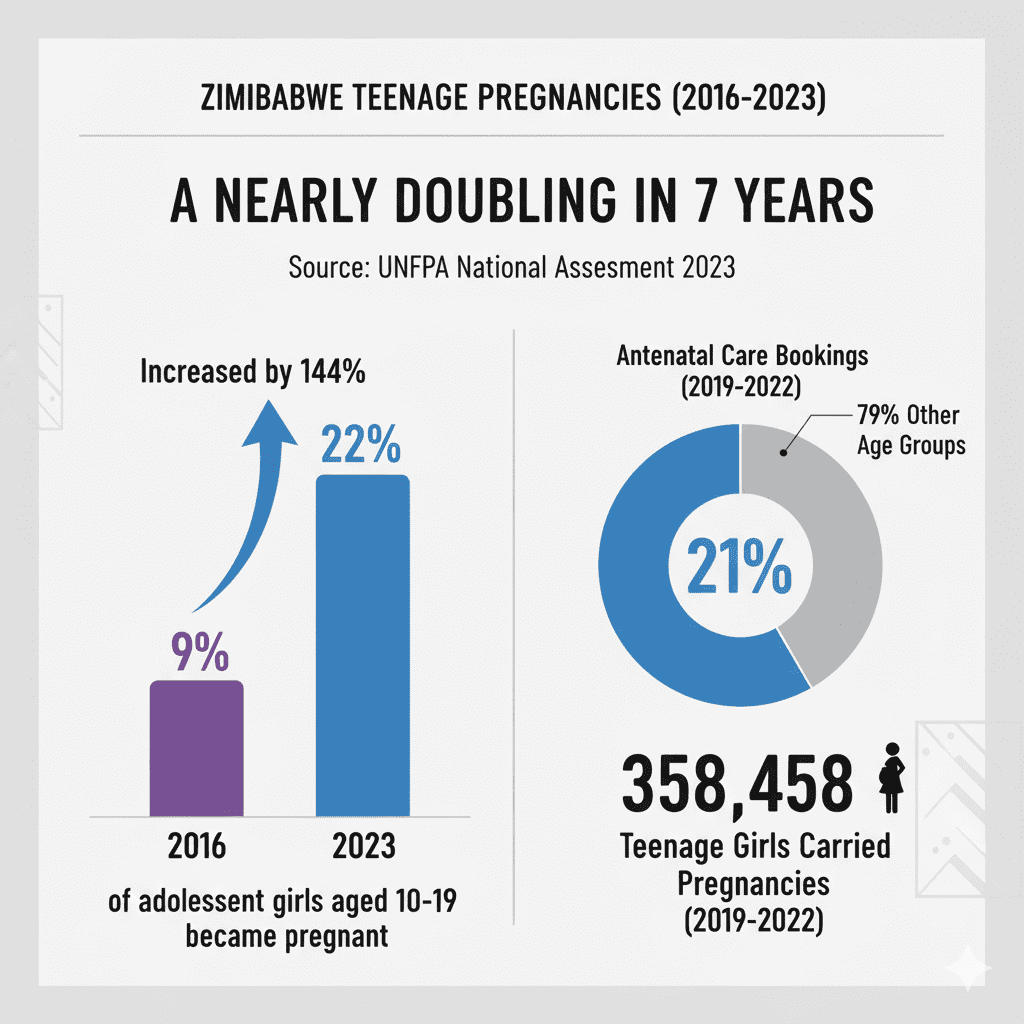

Data from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) paints a worrying picture as teenage pregnancies in Zimbabwe have nearly doubled in just seven years, rising from nine percent in 2016 to 22 percent by 2023.

In that same period, one in five expectant mothers seeking antenatal care was a teenager, which means that more than 358 000, girls aged 10 to 19, carried pregnancies between 2019 and 2022.

Bulawayo North MP, Minenhle Gumede, described these statistics as “disturbing and problematic” in that at 10 years of age, adolescents were clearly not in a position to make serious decisions about their bodies.

“17-year-old teens would rather be writing O’Level exams than giving birth at such a young and vulnerable age,” she said. “This is even compounded by the social arrangements they grow up in where decisions over resources, including women’s sexuality, are communally made at family level.”

Gumede said this meant “lots” of teenage girls were dropping out of school, missing their chances of pursuing professional and trade qualifications.

“As women of tomorrow, the teenage girls will have to rely on their partners to support the families they raise,” she said. “If they have no partner, they will have to struggle, trying to eke out a living in the streets and other informal spaces. Teenage pregnancies reproduce poverty.”

Since teenage pregnancies specifically affect teenage girls, rather than boys, they are central to the perpetuation of gender inequalities.

Zimbabwe has unsuccessfully adopted multiple solutions from government and civil society toward this problem, including education reforms that lower university entry requirements for girls, and the amendment of criminal laws set clear stipulations for child sex abuse.

Education policy and law reforms fall short

The aim for lowering university entry requirements for women was to counter gender disparities caused by domestic chores, while the passing of the 2024 Criminal Laws Amendment Bill classifies anyone under 18 as a child, therefore tightening protection against sexual abuse.

Sanelisiwe Sibanda, who heads the Media and Languages Department at Lupane State University (LSU), described the policy as a progressive step that enables girls to access university education with lower entry points, recognising their effort to succeed under challenging conditions.

“This was meant to make sure girls do not remain behind as far as the social capital of education provides opportunities in life,” she said.

The goal is to encourage girls to stay at school and make sure they get to university. The long term goal was that, cumulatively, there will be a large population of university-trained women who will inspire teenage girls to the value of higher education.

However, this has been unsuccessful.

“Probably the reason is that teenage pregnancy is not merely a personal choice, it reflects intersecting economic, educational, cultural and health‑service dynamics,” said Sibanda.

Lowering university entry points does little to address the root causes of early pregnancies and child marriages, since such measures only benefit girls who manage to complete secondary school.

For many others, pregnancy occurs long before they reach that level, cutting their education short. She added that in some cases, families marry off their daughters early to avoid school fees, a practice that undermines ongoing efforts to keep girls in school and delay early marriage.

Gaps in sex education and cultural taboos deepen teenage pregnancy crisis

Without comprehensive sexual education that empowers young people to make informed decisions about their health, bodies, and future; poor enforcement of child protection laws and cultural taboos continue to leave many adolescents misinformed or uninformed about sexuality and the repercussions of teenage pregnancy.

According to Roselyn, information about her choices when pregnant came from her peers, “I was also afraid of having an abortion and dying.” she said.

Executive Director of the Sexual Rights Centre (SRC), Mojalifa Mokoele Ndlovu, said the current sexual education offered in schools remains inadequate, as it largely focuses on abstinence-only approaches that fail to address the realities of adolescent sexuality.

“To effectively tackle this crisis, we need an inclusive, and age-appropriate Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) that covers sexual health, rights, and relationships. Educators must be properly trained and equipped to deliver lessons in a sensitive, non-judgmental manner,” he said.

He added that access to reliable information and services must be prioritised, alongside active community engagement.

“Parents, guardians, and community leaders should be involved in CSE discussions. Policy support is also essential. We need stronger laws and policies that uphold CSE and adolescent health, while protecting both girls and boys from abuse and sexual violations,” Ndlovu said.

Ndlovu noted SRC was “deeply concerned” about the rising teenage pregnancy rates in Zimbabwe, which was why it runs programmes aimed at addressing this and other issues affecting Adolescent Girls and Young Women (AGYW).

“In partnership with Plan International, we have a programme called My Body, My Future! and part of its activities has been to push for CSE, which we believe is crucial in empowering young people with accurate information to make informed decisions about their bodies, health, and futures,” he said.

My Body, My Future promotes sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) among young people in Bulawayo and Kwekwe through art and media. It focuses on empowering girls and marginalised youth, including those with disabilities, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer or Questioning (LGBTIQ+) communities and young people in vulnerable situations to make informed choices about their bodies and futures.

According to Adrian Rendani Moyo, Ward 2 Councillor in Bulawayo, a major limitation to approaches to solving teenage pregnancy is the absence of honest conversation or intergenerational dialogue with young people.

“Young people need to be assisted to play the lead role in solution finding,” he said. I would like to believe children are being taught to a sufficient level, however, the teaching should be in sync or harmony with what they are taught at home.”

With awareness campaigns failing to penetrate cultural barriers where sexuality is considered taboo, Dr Vusumuzi Sibanda, a legal practitioner, recommends integrating sexual education into schools, making contraception accessible and normalising sex talks.

“Talking freely about sex teaches abstinence but should abstinence fail, protection has to be used and where children are already sexually active even when young, introduce them to family planning,” said the legal expert.

“Chiefs and all community leaders must openly talk about sex, provide education and the necessary preventive amenities. Allow sex talk and sex education should not be a taboo. There must be adequate sex education to children, in particular girl children as young as 12.

Despite the provision of local sexual health and maternal services—including antenatal care, HIV testing, counseling and postnatal support—by the Bulawayo City Council, social stigma and financial constraints hinder access.

Attitudes at Clinics Create Invisible Barriers for Teenagers

At first glance, access to contraceptives for young people in Zimbabwe appears straightforward as clinics do not require parental consent. But in reality, it is not that simple.

According to Bulawayo’s Provincial Medical Director, Dr Maphios Siamuchembu, the policy exists, yet many teenagers still stay away. The reason, several girls say, is the attitude of some nurses, a quiet but powerful barrier that keeps them from the help they need.

“Some nurses give you a bad vibe. Their attitude is just off, they look at you like, ‘so you’re having sex now?’ The way they talk or ask what you want makes you feel judged, like you’re promiscuous or planning to spend the whole night having sex. Sometimes it’s easier to just go to a pharmacy,” Patricia Dube from Gwabalanda.

“There are also long queues at the clinic and everyone can see you waiting, so it’s better to just go to a pharmacy and deal with it fast. Yes, some staff there can also have an attitude, but at least it’s quick, these are cash transactions, you pay, get what you need and leave. Pills cost about US$1 for three or four packs, depending on where you go.”

Across communities, leaders are grappling with how to bridge these gaps. In Gwanda North, Chief Mathema of Enqameni believes the problem starts with knowledge.

Too many families, he said, do not understand the laws meant to protect their children. “Laws are made but never taught to the community,” he explained. “People must learn them in schools, not only when trouble comes.”

Further north, Chief Mbuso Dakamela of Nkayi wrestles with another challenge – where to draw the line between young love and abuse.

“When a 19-year-old and a 17-year-old are involved, the law is not clear,” he said. “Are these pregnancies the result of exploitation, or simply teenagers being teenagers?”

For Dakamela, the solution lies in understanding, not just arrest. “We must explain why sleeping with young girls is harmful,” he said. “A 17-year-old still has a future, she should be in school, planning her life.”

He believes that preventing early pregnancies takes more than laws. It takes stronger sex education, active youth programmes, and families that can meet their children’s needs.

“If children are busy, learning, and cared for,” he said, “they are less likely to make choices that cost them their future.”

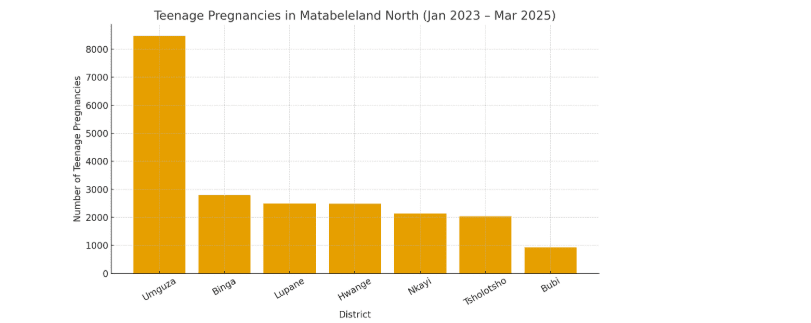

At district level, Umguza recorded the highest number with 8 468 cases, followed by Binga (2 798), Lupane (2 489), Hwange (2,487), Nkayi (2 132), Tsholotsho (2 041), and Bubi (929).

“We Were Poor, and I Was Forced”

Poverty continues to drive early pregnancies in Zimbabwe, forcing many girls into transactional relationships or early marriages.

Data from the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) revealed that more than 30,000 teenagers were married in 2024 in Beitbridge alone, a town in Matabeleland South province.

“Most girls also feel pressure to get nice things that those from well-off families have,” said Dr Sibanda, who is an advocate of minority rights. “There is, then, a need for sex education and easy, free access to family planning, recognising that children are sexually active as early as 12.”

For Zibusiso Ndlovu, now 21, the consequences of poverty were deeply personal. She became pregnant at 14.

“It was pressure from my family,” she said. “We were poor, and I was forced to sleep with a young man who seemed like he could help. But the economic situation was hard for everyone.”

Dr Sibanda said recent education reforms now allow teenage mothers to return to school, a significant change from the past when they were expelled for becoming pregnant.

“In the past, they were seen as bad influences,” he said. “Now, policy allows them back in class, giving girls a second chance and nearly equalising opportunities between boys and girls.”

However, social and economic barriers still make it difficult for many young mothers to continue schooling.

“It depends on whether you have a supportive family or someone to care for your baby,” said Sithulisile, a young mother. “In my situation, that was impossible. We’re a poor family, and everyone is struggling to make ends meet.”

Dr Khanyile Mlotshwa, a cultural studies scholar, said economic hardship and cultural expectations continue to worsen the problem. “In some communities, families prioritise bride price or immediate survival needs over keeping girls in school,” he said. “This pushes many into early unions or risky relationships.”

Parents Say the Ban on Corporal Punishment Has Weakened Discipline

Some parents believe that modern laws protecting children from corporal punishment have eroded parental authority, contributing to rising teenage pregnancies.

Mana Menelisi Thebe, said the loss of respect among young people is fueling the problem.

“Our children no longer follow household rules,” he said. “Parents are afraid to discipline their children because it’s now called child abuse. It’s unfortunate for girls because they are pregnant at an early stage.”

Thebe lives in Dlomoland, Inyathi, Matabeleland North and he blames the ban on corporal punishment, high school dropout rates, and idleness among youth for the trend.

Corporal punishment was outlawed in 2017 through a High Court ruling that declared article 60(2) (c) of the Educational Act unconstitutional. Before 2017, the use of corporal punishment in Zimbabwean schools was allowed.

The law specifically bars teachers from beating schoolchildren in whatever circumstances.

In April 2019, the Constitutional Court ruled that no male juvenile convicted of any offence could be sentenced to receive corporal punishment.

But Prince McLeod Isolengwe Tshawe, the royal leader of the Xhosa community in Zimbabwe, is concerned about the high levels of unemployment in the country.

“In the Xhosa culture, children under 18 should still be in school, not getting married or engaging in relationships,” he said. “If the government created opportunities for the youth, it would reduce these pregnancies.”

From the Midlands Province, Chief Mafala Matshazi of Zvishavane attributed the rise in teenage pregnancies to exposure to social media and changing lifestyles.

“Children now watch things we never saw growing up and rush to imitate them,” he said. “Many live away from their parents, staying with relatives while parents work in cities or abroad. That lack of supervision has consequences.”

In Nkayi, 73-year-old Olivia Moyo lamented what she sees as the erosion of traditional values.

“Children are now uncontrollable,” she said. “In our time, girls waited for boys to make the first move and even then, physical contact was not allowed. Now you see young people hugging and kissing in public without shame. Those teachings we had are gone.”

#NotInMyVillage: A Homegrown Movement Redefining How Zimbabwe Confronts Early Pregnancy

For years, Zimbabwe has tried to curb teenage pregnancies by widening educational access – lowering university entry points for girls and encouraging young mothers to return to school. Yet, classrooms remain half-empty, and many girls never make it back.

Now, a new kind of response is taking shape, one that starts in the villages themselves.

Launched by the National AIDS Council (NAC) and UNFPA, the #NotInMyVillage Campaign empowers young people, aged 10 to 24, to become peer champions against child marriage and teenage pregnancy.

The #NotInMyVillage initiative takes a unique approach by engaging traditional leaders, who are custodians of culture in rural communities, and key opinion figures as champions for positive change. The campaign acknowledges the vital role these individuals play in shaping community norms and values, and it aims to harness their influence to create a supportive environment for adolescent girls.

“We want communities to take the lead in protecting their own children,” said Bekezela Mudzindiko, NAC District AIDS Coordinator. “Our goal is to help adolescents realise their full potential.”

Since its debut in 2023, the campaign has expanded to Bulawayo, where it now carries a local twist—“Not in My Constituency, Not in My Ward,” and “Not in My Household.” Backed by councillors and MPs, the city has embraced the effort as a rallying cry for change.

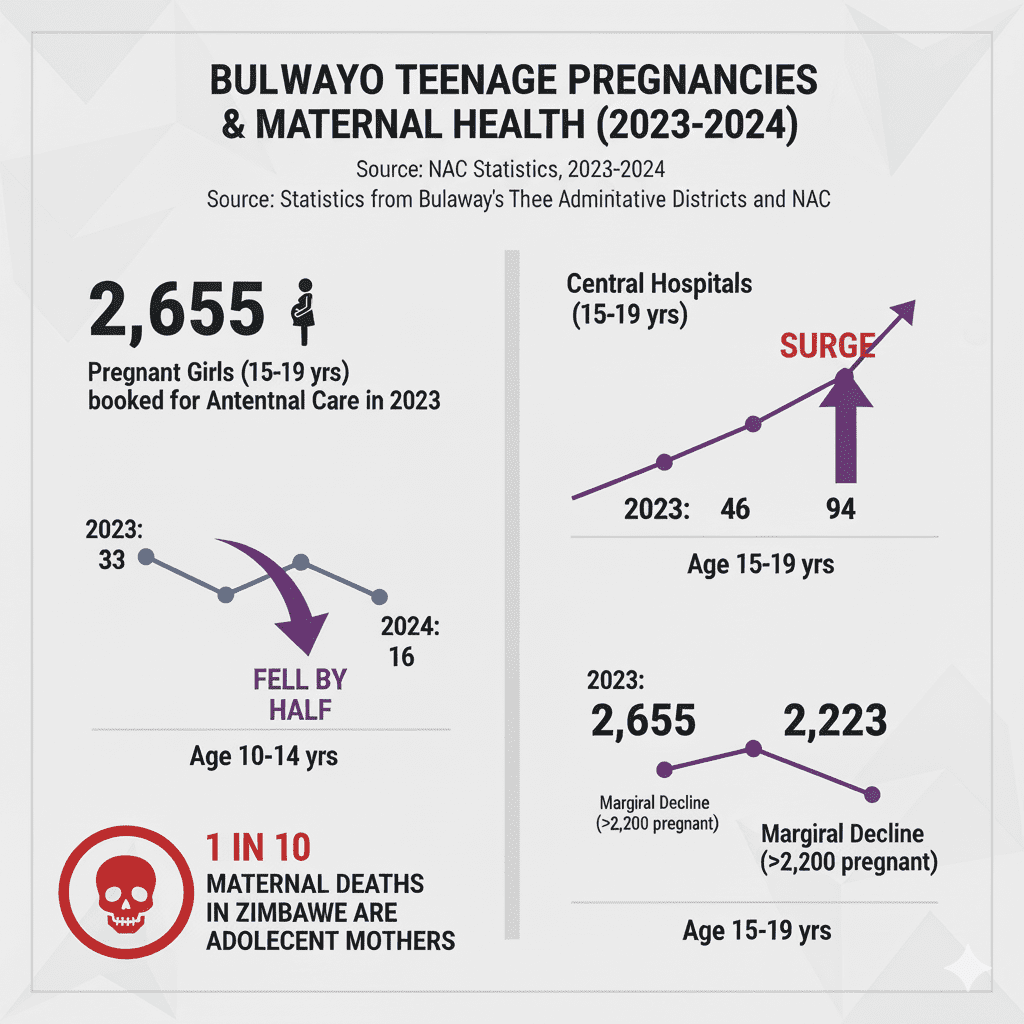

And the results, while modest, are beginning to show. Data shared by NAC’s Bulawayo provincial manager, Sinatra Nyathi revealed that teenage pregnancies among 10 to 14-year-olds in Bulawayo dropped by half – from 33 in 2023 to 16 in 2024. Among 15 to 19-year-olds, numbers fell slightly from 2655 to 2223.

Still, the picture remains mixed. Nyathi said at Central Hospitals, antenatal bookings among older teenagers nearly doubled over the same period – from 46 to 94.

“It’s progress, but we can’t celebrate yet,” said Nyathi.

“16 children barely into adolescence became pregnant this year, that’s heartbreaking. And with more than 2 000 teenage pregnancies in one province, the challenge is still enormous.”

Nyathi added that one in ten maternal deaths in Zimbabwe occurs among adolescent mothers, a statistic that underscores how urgent the fight remains.

The #NotInMyVillageCampaign was officially launched in Mashonaland Central on 26 August 2024, by the health ministry in collaboration with local leaders. That local ownership has since defined the campaign’s expansion to Bulawayo, where community leaders, councillors and MPs who once were worlds apart, now sit together in meetings.

“It was encouraging to have councillors and MPs in the same room,” said NAC District Officer, Bekezela Mudzindiko. “They even pledged to organise meetings in their wards.”

“Traditional leaders are the custodians of culture in their areas,” said NAC Programmes Officer, Douglas Moyo. “If everyone participates, marrying off children will be a thing of the past.”

Chief Mayenga Fuyane of Maphisa believes this work must go beyond policy.

“Let’s go back to basics,” he said. “A child didn’t belong to one household but to the community and when a child misbehaved, they were corrected by everyone.”

The campaign’s strength lies in that very principle – shared responsibility. Through regular feedback sessions and training for local leaders, NAC teams are helping communities take ownership of the initiative.

“Flexibility and ongoing dialogue have kept the momentum,” said Mudzindiko. “When communities feel heard, they protect their own future.

*Not her real name.

Editor’s note: This story is part of our effort to bring a Solutions Lens to investigative reporting on gender bias, particularly in reproductive health. Guided by four pillars—the response to the problem, the evidence for that response, its limitations, and the insights that can be replicated—we aim to show not just the problems, but how people are responding and building resilience in the face of challenges.

This story has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems, http://solutionsjournalism.org

Leave a comment