By Busani Bafana

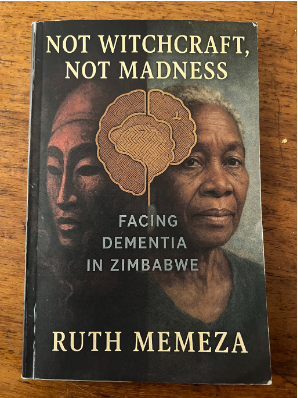

Ruth Memeza is a social entrepreneur, motivational speaker and author. CITEZw sat down with Ruth to unpack her book, Not Witchcraft, Not Madness: Facing Dementia in Zimbabwe.

What drew you to study dementia that is the focus of your book?

My journey into dementia was not academic at first. It was deeply personal. I encountered dementia through lived experience, through caregiving, through watching families struggle silently, confused, ashamed, and unsupported. I realised quickly that dementia was misunderstood, mislabelled and mishandled, often at great cost to dignity and relationships. I wrote this book because I could no longer accept silence, stigma, or suffering being normalised.

What has been your personal experience with dementia?

I have lived it from many angles, caregiver, observer, trainer, advocate. I have seen tenderness and cruelty, devotion and abandonment. I have seen how love alone is not enough without knowledge, support, and policy. Those experiences shaped every page of this book.

“Not Witchcraft, Not Madness” – what does that mean?

In Zimbabwe, unexplained changes in behaviour, memory loss, confusion, or aggression are often interpreted through spiritual or moral lenses. People are accused of witchcraft. Others are labelled mad. The title is a direct challenge to those narratives. Dementia is neither witchcraft nor madness. It is a medical condition-but also a social, cultural, and human issue. Naming it correctly is the first step toward dignity.

Coming to the second part of the title, what does “Facing Dementia in Zimbabwe” look like?

Facing dementia in Zimbabwe means navigating a fragile health system, limited diagnosis, cultural stigma, and overwhelming family responsibility- mostly carried by women. It often means late diagnosis, denial, fear, spiritual confusion, and care without guidance. Yet it also means resilience, family closeness, and community care when it works well.

Currently, Zimbabwe does not have a comprehensive, stand-alone dementia strategy. Dementia is often hidden within general mental health or ageing discussions, leaving major gaps in care and policy.

What are the early signs of dementia?

Early signs of dementia are often subtle and may be mistaken for normal ageing or stress. However, when these changes begin to interfere with everyday life, they deserve attention.

You have memory loss affecting daily life. This goes beyond occasionally forgetting names or appointments. A person may repeatedly ask the same questions, forget recent conversations, misplace items in unusual places, or struggle to remember important events. The key difference is that reminders no longer help.

There is also confusion with time or place. Someone may lose track of dates, seasons, or the passage of time. They might become disoriented in familiar environments, forget how they got somewhere, or struggle to find their way home.

You have people facing difficulty in making decisions. Tasks that once felt simple, managing money, planning meals, following instructions, or making choices, can become overwhelming. Judgment may be affected, leading to poor or unsafe decisions.

Another sign of dementia is personality or behaviour change. Dementia can affect mood and behaviour. A person may become unusually irritable, anxious, suspicious, withdrawn, or emotionally flat. These changes are often distressing for families, especially when they seem “out of character.”

People also withdraw from social activities. Because of confusion, embarrassment, or difficulty following conversations, individuals may pull away from friends, family gatherings, church, or community activities they once enjoyed.Early recognition allows families to seek support, rule out reversible causes, and plan with dignity rather than reacting in crisis.

How do spiritual and cultural beliefs shape dementia experiences?

Beliefs can either harm or help. When distorted by fear, they fuel stigma. When guided by Ubuntu, respect for elders, and compassion, they create community-based care. The challenge is correcting misinformation while honouring culture.

Dementia is not witchcraft, punishment, or madness. Challenging harmful beliefs helps protect vulnerable people from neglect, abuse, and shame.

Can dementia risk be reduced?

Yes. While dementia cannot always be prevented, research shows that risk can be reduced or delayed by addressing lifestyle and health factors, especially when started early or maintained across adulthood.

There is a need to manage blood pressure and diabetes. Good control of conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol protects brain health by reducing damage to blood vessels that supply the brain.

Staying socially engaged. Regular interaction with others, family, friends, faith groups, or community activities, helps keep the brain active and reduces isolation, which is a known risk factor.

Besides, physical activity is also important. Regular movement such as walking, gardening, dancing, or household chores improves blood flow to the brain and supports overall cognitive health. In addition, mental stimulation helps reduce the risk of dementia. Activities that challenge the brain, reading, learning new skills, puzzles, storytelling, or even meaningful conversations, help build cognitive reserve.

Eating a healthy diet has been found to reduce the risk of dementia.Diets rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, fish, and healthy fats support brain function. Reducing excessive sugar, salt, and processed foods is also beneficial.

What practical advice would you give to families living with dementia?

Living with dementia is challenging, but families do not have to face it alone. Practical steps can make daily life more manageable and preserve dignity for everyone involved. For instance, people should seek help early. Do not wait until there is a crisis. Early medical advice, community support, and information can reduce fear and help families plan realistically.

I would also add that we should learn about dementia. Understanding that dementia is an illness, not stubbornness or bad behaviour, helps families respond with patience rather than frustration.

I would advise sharing caregiving responsibilities.Caregiving should not fall on one person alone. Sharing tasks reduces burnout and allows caregivers to rest and remain emotionally present. Besides, families should maintain routines for their loved ones living with dementia. Predictable daily routines provide comfort, reduce anxiety, and help the person with dementia feel safe and oriented.

It is also important to protect the dignity of people living with dementia. Families must speak respectfully, involve the person in decisions where possible, and avoid talking about them as if they are not present. Dignity remains even when memory fades.

You mention that dementia is a human rights and gender issue, why?

Because dementia strips people of autonomy if systems are not in place to protect them.

And because caregiving overwhelmingly falls on women, daughters, wives, daughters-in-law – often without pay, recognition, or support. Ignoring dementia means ignoring women’s labour, elder rights and care justice.

Not Witchcraft, Not Madness: Facing Dementia in Zimbabwe published by Wing Up Publishing, ISBN 978-1-77928-629-1 is available at Dingani Bookshop, Bulawayo and Airport Bookshop, Harare.