Bulawayo’s city centre, like other Zimbabwean cities, is undergoing a quiet but profound transformation where established retailers and high-end shops, which once anchored the formal economy are shutting down, resulting in the space they were taking being subdivided and rented to clusters of small informal traders.

In these same spaces where brands like Haddon & Sly, Edgars, Woolworths and Topics once sold regulated, locally supplied high-value goods, shelves are now packed with cheap, often counterfeit products, many of them smuggled into the country and sold at low prices.

The rapid spread of informal shops is not merely a change in the retail landscape; it is a visible symptom of deeper economic distress bedevilling the country. As formal businesses close under the pressure of rising costs, shrinking demand and unfair competition, an underground market sustained by smuggling and illicit financial flows is filling the vacuum, further undermining Bulawayo’s struggling industries and accelerating de-industrialisation and unemployment.

Bulawayo has long been regarded as Zimbabwe’s industrial hub. It was home to textile manufacturers, food processors, metal fabricators and clothing factories.

But industry leaders say the playing field has become dangerously uneven, threatening the survival and vibrancy of the city.

Local manufacturers are competing against counterfeit detergents, clothing, electronics, cosmetics and food products that enter the market at a fraction of the cost of legitimate goods and most of these products are sold in the small shops located around 6th Avenue.

Many of the products are smuggled through porous borders or disguised through trade misinvoicing, allowing importers to evade customs duty VAT and income tax.

Some business premises across Bulawayo are also selling low-cost imports from China, contributing to the surge in illicit trade.

Large formal retailers, burdened by rent, wages and taxes, are losing customers to informal shops selling cheap goods.

The closure of the giant retail clothing company, Edgars Stores Limited branch popular known as ‘Edgars Tredgold’ in 2023 located at the corner of Herbert Chitepo Street and Leopold Takawira Avenue in the city centre, bears testimony of the problems affecting the city. For decades, Edgars Tredgold, was one of the most prestigious shops in the city, but like other law-abiding retailers, it was struggling due to the flooding of cheap imports and rising overheads, culminating in the closure.

Just like the once prestigious Haddon & Sly, opposite the City Hall, the shop has now been partitioned to smaller informal traders spaces symbolising a broader erosion of formal retail, where established businesses are slowly being crowded out by an informal economy sustained by smuggling, cheap products and counterfeits.

Established brands such as OK Zimbabwe have closed outlets and scaled down operations countrywide, unable to compete with the growing network of informal traders.

An investigation reveals that counterfeit goods do not simply “slip” onto the market. They are pushed through by organised networks involving cross-border runners, wholesalers in Musina, corrupt customs officials, dishonest police officers and retailers who knowingly stock fake products.

During busy periods like the just ended festive season, congested shops in Bulawayo’s CBD become hotspots for counterfeit trade.

A small grocery operator, Tariro, who spoke to this reporter as part of this investigation, admitted that many informal traders sell smuggled goods and avoid accountability by paying routine bribes.

“Police from the licensing department from Drillhall collect money every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, usually US$3, US$5 or US$10. Some days it can be US$30,” she said.

National Police Spokesperson Commissioner Paul Nyathi however said they have not received such reports and requested for formally lodged reports to the police so that investigations can be conducted.

“The law is always clear, anyone who engaged in criminal activities whether it’s a police officer, member of the public or anyone for that matter, the law will always take its course without fear or favor,” said Commissioner Nyathi.

Although the small grocery shops owners have customs payment receipts for cash assessment where they pay annual fines for anti-smuggling under Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA), the move is not helping as counterfeit goods continue to flood the market.

“We buy from ‘amakula’, Pakistanis in Musina, South Africa. We use Beitbridge or sometimes the Botswana border (Plumtree Border Post) because it’s cheaper,” Tariro said.

Counterfeit detergents such as toothpaste, body lotions, shampoos and food products dominate informal shelves.

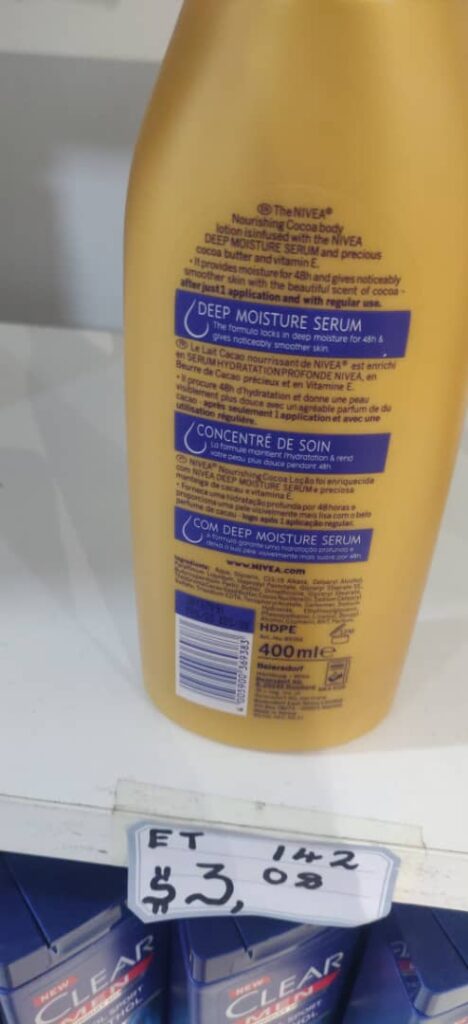

A fake body lotion such as Nivea Q10 can sell for as little as US$3 from Chinese-owned shops and local outlets downtown around Fife Street, as well as 5th and 6th Avenue. Formal shops and pharmacies sell the same product for US$10. Shampoos like Head & Shoulders are sold for as little as US$2, prices that legitimate retailers cannot match without operating at a loss.

The pricing gap has devastating implications for local industry. When consumers shift to cheaper counterfeits, factories lose orders, production slows, legit businesses suffer and jobs disappear.

Branding differences are often subtle.

“For example, toothpaste such as Colgate, the original is written ‘Colgate’ on the left and ‘maximum’ and other details on the right side; the fake one is vice versa,” Tariro says.

CITE observed the 100ml of Colgate being sold for a US$1 in small shops and US$2.50 being sold at a pharmacy.

“We have products such as Gentle Magic, baked beans (Koo beans), Colgate, body lotions. Many customers can’t recognise that it’s fake unless they have a picture to compare.

“People don’t know how to spot fake products, it’s only when they react or something (when they know that the product is not genuine). Most of the gentle magic products being sold here at the market place and other small shops are fake, ‘vanhu vonaita kukwatuka face (some people’s faces are literally peeling off because of fake products’,” she said.

For consumers, spotting fake products has become increasingly difficult.

A consumer, Nozibelo Mathonsi who had an experience of fake products after buying gentle magic soap and nivea roll on at a small shop located at Herbet Chitepo and 6th Avenue (where there was former Tilus supermarket )said spotting counterfeit goods is nearly impossible for untrained buyers.

Mathosi also learnt the hard way on counterfeit goods after buying sauvage Dior perfume from a runner.

“The truth is it’s hard to spot fake products with a naked eye, plus you won’t be trained to know how to identify them. I will give an example of beauty products we use; the people imitating those products make sure they copy everything to the dot, from packaging to the words written,” she said.

Mathonsi said only the tiniest details, such as sealing, may expose a counterfeit item.

“But also for someone who wants to make money, they can perfect their skill in that department, so what will be left now is for us to learn the hard way because others are so mean that even the pricing will be the same as the original products. But in cases where you see that this is too affordable, you should see that there is a problem. Why is it too affordable? Where are they stocking from for it to be too cheap?” she said.

She said in some instances, consumers only react after buying a product.

“We learn the hard way in the sense that if it’s a product you are using on your face, your face is going to react and when you trace back you will notice that you started reacting after using the product, then you will know it’s a fake product. That is it with your body lotion, body washes, face products.”

Mathonsi said other fake products that trouble consumers include gadgets such as mobile phones.

“It’s really hard to tell because you can buy a fake iPhone or Samsung thinking it’s a proper thing because it looks proper. With phones, others will tell you that you can spot a fake phone through weight check,” she said.

She added that nowadays it is even hard to differentiate original sneakers from fake ones.

“Unless you are that person who is obsessed with checking authenticity, you won’t know. Nowadays even fake sneakers have a QR code scan. You scan your sneaker, it takes you to the Adidas or Nike shop. I don’t know how they do it but it’s now there, so spotting fake products is tricky it needs people who study those things,” said Mathonsi.

Another consumer, Chantelle Manyika, recalled buying toothpaste that tasted like ashes and detergents that were too watery to work effectively at a shop located along 6th avenue.

“They may as well seem identical, but there will be something amiss with the product. For example, toothpaste, if you haven’t noticed, it has different sizes. At some point I bought 140ml; upon opening the toothpaste, it tasted like ashes, yet it was very cheap.

“You have detergents such as Domestos; the fake one is too liquid while the original one lasts longer. It doesn’t function to the spot,” said Manyika.

She added that for facial products, fake versions tend to have an awful smell compared to originals.

“Overall, it’s hard to differentiate a fake product; your face would only react, peel off or have pimples. These products are made to almost perfect,” she said.

These products are getting into the country through smuggling networks who exploit weak border controls and corruption

A cross-border transporter, who requested anonymity said smugglers exploit loopholes at the Zimbabwe–South Africa border.

“When it comes to exiting entry points, on the South African side we just declare the goods, they don’t normally search. For vehicles ferrying ‘hot’ goods, when we get to the middle of the bridge approaching the Zimbabwean side, we pay some money to security agents and remove all the goods and use the route under the bridge. Every checkpoint we pass, we pay something to security agents,” he said.

He said some transporters use “inyamazana” people who smuggle goods through the bush from the South African side to the Zimbabwean side of the border. The goods are then loaded into vehicles after being smuggled.

He added that alcohol counterfeiters refill expensive bottles with cheap alcohol.

“It’s hard to tell fake products, but when it comes to alcohol, each region has its certain percentage, so what happens is these people take expensive bottles, put cheap or fake alcohol and put their labels,” he said.

He said counterfeit dealers rebrand expired products.

“Expired goods are not thrown away, they repackage them and we bring them to Zimbabwe,” he said.

Beyond health and safety risks, the counterfeit trade fuels illicit financial flows, including smuggling, trade misinvoicing, tax evasion and corruption.

According to Zimbabwe’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment estimates that Zimbabwe loses about US$1.23 billion annually from predicate offences such as smuggling and tax evasion.

The FIU 2024 annual report identified six major sources fueling illicit money circulation: smuggling (US$920 million), illegal trade in gold and precious stones (US$880 million), entrenched corruption (US$730 million), fraudulent activities (US$500 million), tax evasion (US$300 million), and drug trafficking (US$170 million).

Presenting the 2026 National Budget, Finance Minister Professor Mthuli Ncube said the Government remains committed to strengthening policies that combat money laundering, terrorism financing and related financial crimes.

He said the Financial Intelligence Unit and the Ministry had completed Zimbabwe’s third National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, which found that crimes such as smuggling, tax evasion and illegal dealings in minerals and drugs are occurring with increased frequency.

Zimbabwe has since adopted a new Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Financing of Terrorism Strategy (2025–2029) to guide regulatory and law enforcement bodies.

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) notes that Africa is highly vulnerable to counterfeit products, estimating that 30–60 percent of globally traded goods are fake.

Counterfeit goods have a disastrous impact.

Speaking during the Annual Consumer Conference at the Zimbabwe International Trade Fair in November last year, Steven Kamu Kama, representing COMESA CEO Willard Mwemba, said that counterfeit medicines contribute to 100 000 direct deaths and 500 000 deaths from treatment failures.

“Now, medicine is a serious problem . If you look at what is happening, it kills directly… about 100 000 people in Africa, but also indirectly, it kills about 500 000 people simply because they are taking the wrong medicine.

“So, you take the wrong medicine, it fails to treat malaria, it fails to treat the other problem you have, and you end up dying just because you took wrong medicine. Counterfeit is contributing to that problem.”

“One hundred percent of total electronics trade in counterfeit products causes economic and social hazard and health risks. Counterfeit electronics contribute to 2.9 million tonnes of generated waste,” said Kama.

In Zimbabwe, while authorities have not published national death toll specifically attributed to counterfeit products such as alcohol, the media has however published stories of people dying after consuming fake alcohol, for instance in 2019 three people died after binging fake Jameson Irish Whiskey.

Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC) Chief Executive Officer, Christopher Mugaga said manufacturing is the most affected industry by counterfeit goods as they are cheap, substandard and due to poverty levels in the country, these goods will be more affordable.

“It kills process to industrial recovery,” he said

He warned that counterfeits are accelerating de-industrialisation cities like Bulawayo, killing jobs and discouraging investment.

“When industry is competing with such products, no company will think of manufacturing blankets when there are blankets smuggled from South Africa, it also kills employment,” he said.

Mugaga said counterfeit products are also facilitating the urban decay in Bulawayo as economic activity is low, “ thus why when you get to Bulawayo, the buildings are from Mbuya Nehanda era because there is no business.”

He added that while corruption is real and happening, porous borders are also facilitating the entry of counterfeit products .

“We possible have seven official points of entry but if you look at unofficial points, they can even reach 30, so all that is facilitating the proliferation of counterfeit products . Besides corruption by border agents, goods come through porous entry point, so there is a need for attention and invest in technology to monitor the perimeters”.

Mugaga said the solution lies in having policies which promote formal production.

“The measures currently (in place), especially, on taxation and banking front are anti- manufacturing,” he said.

Industry and Commerce Minister Mangaliso Ndlovu said his Ministry conducted research whose findings will be presented to Cabinet, highlighting the extent of the problem.

“We had a huge problem that we needed to address. We are happy that we have made some progress, but a lot needs to be done on smuggling as well as counterfeit products,” he said.

Ndlovu said the Ministry is recommending strengthened institutional capacity at ports of entry.

“That includes drone surveillance that is there in some areas and other areas we might not want to make public, but we realise that there is need for institutional strengthening and capacitation just to make sure we are a step ahead of those who want to smuggle things,” he said.

In September 2025, Minister Ndlovu was quoted in the media as saying, “Since April 2025, a total of 54 443 businesses were inspected nationwide. From those inspections, 86 962 non-compliant products have been removed from circulation, 6 823 compliance notices issued and 5 656 prosecutions finalised.”

Consumer Protection Commission (CPC) Director for Research and Public Affairs, Kudakwashe Mudereri, said counterfeiters target high-demand goods such as popular food brands, clothes, electronics, alcohol and personal care products.

He warned that fake products pose serious risks, including unsafe ingredients, allergic reactions, food poisoning, ineffective medicines and fire hazards from poor-quality electronics.

Mudereri said many shoppers rely on price as the main deciding factor when buying, making them vulnerable to fake and unsafe bargains. He urged consumers to watch out for poor packaging, unusually low prices, missing expiry dates, inconsistent colours, broken seals and electronics without warranties.

“If something feels ‘off,’ consumers should avoid the product,” he said.

“Consumers should remember that counterfeit trade is not just a consumer issue. It affects public health, national revenue and fair competition in the economy.

Programs and Campaigns Manager at Accountability Lab Zimbabwe, Beloved Chiweshe said the key enabler in the counterfeit goods is the absence of robust Beneficial Ownership Transparency (BOT) meaning authorities cannot identify the real individuals or entities behind companies involved in importing, distributing or selling counterfeit goods.

He said in Zimbabwe, this opacity enables traders in counterfeit food, beverages, cosmetics and medicines to integrate their proceeds into the economy without clear ownership records, reducing traceability if financial flows for tax, customs and law-enforcement purposes.

“A recent Financial Intelligence Unit(FIU) risk assessment found that corporate structures in Zimbabwe are exploited to conceal beneficial owners and facilitate money laundering, corruption and smuggling, generating an estimated US$1.23 billion annually in proceeds from predicate offences like smuggling and tax evasion,” he said.

Chiweshe said formal regulatory standards exist for food, pharmaceuticals and other consumer goods, but enforcement is inconsistent.

“For example, MCAZ and police periodically intercept smuggled pharmaceuticals, such as counterfeit rabies vaccines, but the pathways through which they enter remain unclear, often facilitated by porous borders and high consumer demand for cheaper alternatives,” he said.

He added that there is a need for Civil Society to support consumer education campaigns on risks of counterfeit products and how to identify them.

“A multi-stakeholder strategy is essential: Government institutions should enhance market surveillance and interagency cooperation, including targeted inspections with Standard Association of Zimbabwe (SAZ), Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ), and Consumer Protection Commission (CPC). The Private sector should invest in product traceability technologies (e.g QR verification codes supported by platforms like Buy CCZ verified initiative to help consumers and regulators authenticate products,” said Chiweshe.

Efforts to get a comment from the Head of Corporate Affairs for ZIMRA, Francis Chimhanda, did not yield any results after numerous efforts to contact him; he was not picking up his calls or responding to messages sent to him.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today