By Linda Mujuru

On a busy Monday morning in central Harare, dozens of young people lined a narrow corridor inside Boka Islip House on the seventh floor outside room 702.

All of them were clutching copies of their identification documents and job applications.

They were all chasing the same promise: employment in retail shops as merchandisers and shop assistants.

Many of them had responded to job advertisements circulating widely on WhatsApp groups, promising immediate placement in supermarkets and other retail outlets.

But what appeared to be a rare opportunity in a country battling high youth unemployment soon revealed troubling signs of a coordinated scheme exploiting job seekers.

This journalist went undercover to investigate and uncovered stories of deceit and exploitation at an industrial scale.

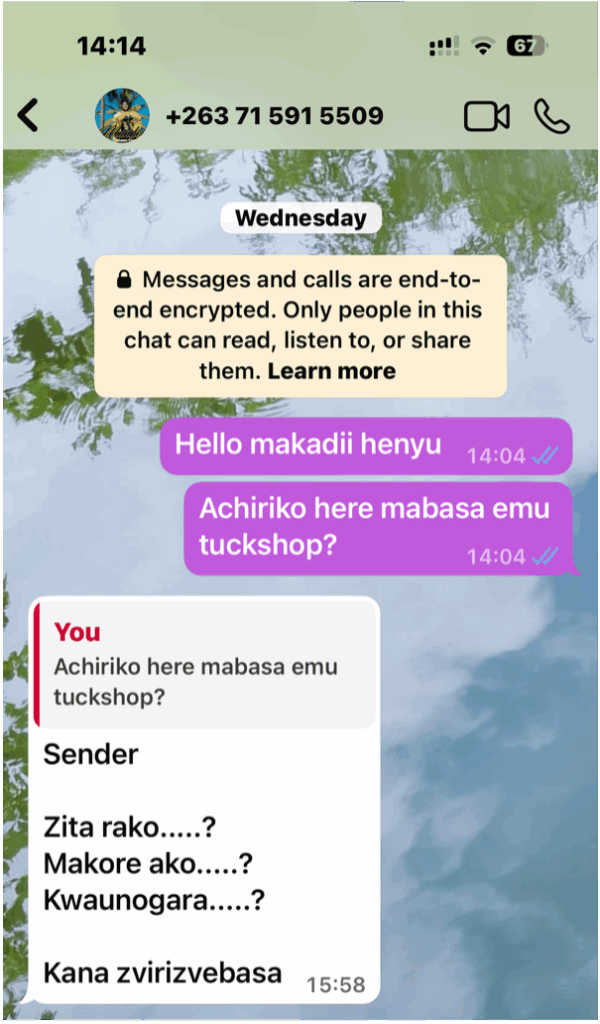

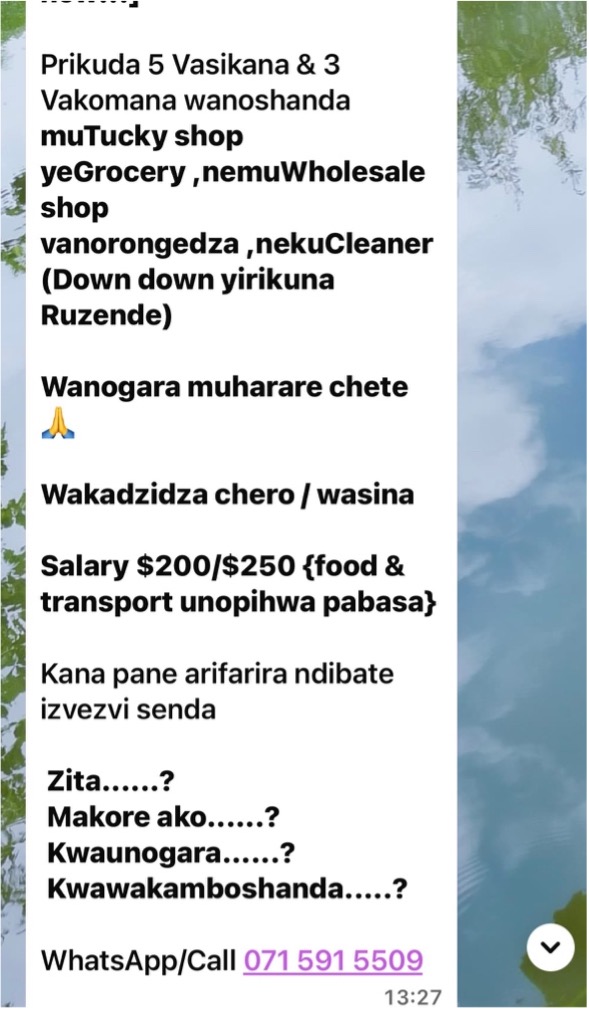

The particular job advertisement was posted in a WhatsApp group dedicated to sharing online novels; the platform occasionally carries advertisements outside its core focus.

It promised vacancies for shop merchandisers and retail assistants in several Harare supermarkets.

Applicants were instructed to submit their names, address and contact details before being invited for interviews.

Within minutes of expressing interest, this reporter received a message confirming an interview appointment at Boka Islip House, a commercial building located in Harare’s central business district.

The instructions were brief: bring identification documents and arrive by 8.30am.

On arrival at the seventh floor, the reporter found a long queue of mostly young men and women, many of whom appeared to be recent school leavers or graduates.

Some had travelled from surrounding high-density suburbs, while others said they came from as far as Chitungwiza and Norton.

Desperate job seekers

Despite the steady movement of applicants into interview rooms, the queue barely shortened. During the hour the reporter observed the scene, close to 30 individuals were interviewed, while others continued to trickle in.

“We are just trying our luck,” said Norman Jati, a 23-year-old job seeker who was waiting for his turn in the interview.

Jati said he had responded to the WhatsApp advert after months of searching for employment.

“I am just trying my luck,” he said. “To be honest, I don’t know if this is genuine or not, but there are very few opportunities out there, so you end up taking chances.”

However, this is not his first time responding to such vacancies. Jati said he had previously encountered similar arrangements where job seekers were placed in retail shops under the guise of attachment or training, but never received payment.

“They work with grocery wholesalers and tuckshops,” he said. “They send people for attachment, saying it’s training, but it is really free labour.

“After some weeks, they just tell you the placement is over and you never get employed,” he added.

Zimbabwe’s prolonged economic challenges and high unemployment rates have created fertile ground for such schemes.

According to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency’s 2025 Labour Force Survey, nearly half of young people aged between 15 and 35 are not in education, employment, or training, leaving many desperate for opportunities.

While applicants waited for interviews, an unexpected development unfolded. Three police officers arrived at the offices and entered the premises where they interacted casually with the organisers.

During the encounter, the reporter overheard one officer telling the organisers to “hurry up and give us money so that we can go.”

The officers remained inside briefly before leaving, while interviews continued uninterrupted.

When the reporter’s turn came, she was ushered into a small office where three female interviewers conducted a brief assessment.

Questions focused largely on experience, and the interviewers were quick to point out that training was a prerequisite.

Paying to get a job

The reporter was informed that successful candidates were required to undergo training for a US$25 fee.

After completing the training, candidates would be placed at supermarkets for a two-week unpaid attachment.

The organisers described the attachment as a pathway to permanent employment but provided no written contracts, employer details, or guarantees of placement.

Payment instructions were informal, with candidates encouraged to pay immediately to secure their training slots.

For many applicants, the US$25 training fee represents a significant financial sacrifice.

Several individuals interviewed outside the building said they had borrowed money from relatives or used savings meant for transport and food.

Angela Mapokotera (34) has been looking for a job for the past four months since she gave birth.

“I was told to bring money to get a job and I was pinning my hope on it,” she said.

“I have a husband, he works but the money is not enough and I needed to get employed so that I can take care of my family.”

Mapokotera said many of these job adverts usually ask for various fees ranging from US$10 to as high as US$40.

Ruth Gwese, a 28-year-old mother of one, has gone through the attachment process and described it is a scheme to provide free labour to supermarkets and other retailers.

“It’s a scam,” Gwese said. “I was placed on attachment for three months, working for free, using my own transportation money, but after the three months of working, I was told that was the end.

“I realised that some of these job scammers work in cohorts with small shop owners to provide them free labour.

“It’s a win-win situation for them because the agent gets the agent fee and the shop owner gets free labour for three months, after that they get other new people.”

Jati said he will keep on trying, and one day he will be lucky

“You just hope that maybe this one will work out,” he said. “There are no jobs out there. I will keep on trying my luck.”

Charging job seekers is unlawful

Innocent Rice, organising secretary for the Progressive Domestic and Allied Workers Union, said the recruitment agents and employers were violating the law.

“It’s unlawful to charge jobseekers a fee, its unlawful,” Rice told CITE.

“In terms of the Labour Act, there is no provision that says people on attachment, training or internship are not entitled to a salary.

“The fact that there is a service to an employer, you become an employee, whether on an internship, training, or you are an employee,” he said.

“By not giving any salary, the employer is violating the rights of an employee,” added Rice.

The Labour Act [Chapter 28:01] regulates employment practices and emphasises protection against unfair labour practices, including exploitation and misleading recruitment processes.

Additionally, the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act [Chapter 9:23] criminalises fraud and misrepresentation.

According to law, individuals who knowingly mislead job seekers into paying fees for non-existent employment opportunities may be liable for prosecution.

The Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare has previously warned against employment agencies and individuals demanding upfront payment for jobs, noting that legitimate employers typically cover recruitment and training costs.

Criminals preying on job seekers

Other scammers misrepresent to victims that they are recruiting on behalf of non-governmental organisations and parastatals. The victims are made to pay for the non-existent jobs.

In January, the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) said it had noted a proliferation of fraudulent online advertisements claiming offer recruitment and training opportunities for rangers.

ZimParks said it does not charge fees for recruitment or training processes and advised anyone who encounters such scams to report them immediately to the relevant authorities.

“Members of the public are urged to exercise extreme caution and due diligence before enrolling in, or making any payments towards such alleged recruitment or training programmes,” the organisation said in a statement.

Some of the job scams have turned tragic, especially for women who have been gang raped by unknown people.

In June last year, police issued a warning to job seekers to be wary of people offering employment using social media platforms after a Chitungwiza woman was gang raped.

The 30 year-old woman was allegedly contacted by an unknown woman through WhatsApp and was offered a job as shopkeeper in Domboshava.

Desperate to land the job, the woman followed the instructions and went to Mungate Business Centre where she was told to wait for some people to pick her up at a bus stop.

A few minutes later she was approached by two men who claimed to have been sent by her new employer. Instead of taking her to her new job, the men took her to Borrowdale where they robbed her of her belongings and took turns to rape her.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today