Despite a slight rise in tolerance towards homosexuality in deeply conservative Zimbabwe, much like in many other African countries, advocates for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI) rights continue to face significant backlash.

Over the years, the number of organisations pushing for LGBTQI recognition has steadily grown. From the pioneering Gays and Lesbians Association of Zimbabwe (GALZ), established in 1990, the landscape has expanded to include others such as the Centre for Sexual Health & HIV/AIDS Research (CeSHHAR), Youth Gate Zimbabwe, My Age Zimbabwe, Zim Sunflower, Intersex Community of Zimbabwe, Trans Research Education Advocacy and Training Zimbabwe, and the Sexual Rights Centre. Yet, despite this expansion, many of these organisations struggle to gain traction publicly or on social media, where their posts often receive minimal engagement.

This sentiment analysis of replies to social media posts by four accounts – namely GALZ, The Feminist, UNDP HIV and Health, and the United States Embassy in Zimbabwe – illustrates the contrasting forces of tolerance and resistance that shape Zimbabwe’s LGBTQI discourse.

The language used in the reactions documented illustrates how homophobia circulates within African digital spaces, reinforcing a discourse that frames LGBTQI people as threats requiring containment. They also reveal how online platforms function as spaces where physical violence and intimidation against queer organisations are normalised and even justified.

The analysis also shows a consistent pattern, which is that while Zimbabwe’s LGBTQI organisations and allies maintain a visible and growing presence on social media platforms like X, public responses overwhelmingly reveal cultural resistance and entrenched homophobia. Positive engagement tends to come from within the LGBTQI community or aligned activists, whereas broader Zimbabwean audiences often respond with hostility or not at all.

Backlash and Limited Support for GALZ

On 13 January 2025, GALZ posted: “We’re Back and Ready to Serve You! #backtowork #NewYear2025 #galz.”

Despite a reach of 5,199 and engagement of 16, the most visible reply was negative. Ghetto (@Ghetto_YutZim) retorted: “Hey, get away with your chit chat,” signifying open rejection of GALZ’s work.

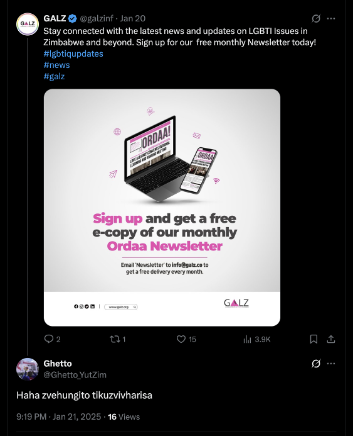

A similar pattern emerged with the 20 January 2025 tweet urging people to sign up for a newsletter: “Stay connected with the latest news and updates on LGBTI Issues in Zimbabwe and beyond…” The post drew both positive and negative responses. “Awesome stuff,” wrote GayProphet (@verygayp), a user whose identity signals affiliation with LGBTQI advocacy. Meanwhile, Ghetto (@Ghetto_YutZim) responded: “Haha zvehungito tikuzvivharisa (we will ensure that we shut down that which has to do with homosexuality).” The use of “zvehungito”, a derogatory Shona term targeting the LGBTQI community, highlights how deeply rooted homophobic sentiments remain among many ordinary citizens.

Screenshots of replies by @Ghetto_YutZim to GALZ posts on X.

Even on Valentine’s Day, when GALZ posted a simple celebratory message, the two supporting replies again appeared to come from advocacy-aligned users rather than general members of the public. Similarly, on 21 February’s National Youth Day and on #IDAHOBIT2025, GALZ continued to receive positive reinforcement almost exclusively from GayProphet @verygayp, reinforcing a pattern: approval tended to come from within the movement, while rejection or silence dominated broader engagement.

In response to GALZ’s 31 May 2023 tweet expressing solidarity with Ugandan LGBTQI communities affected by the Anti-Homosexuality Act, the backlash on X illustrates how appeals to Pan-African identity are often mobilised to delegitimise queer rights advocacy.

For instance, a Ugandan user, Matua Job Richard (@job_matua), questioned GALZ’s involvement, framing LGBTQI rights as “anti-African” and driven by “usual suspects,” a phrase commonly used to imply Western interference. This response, along with 33 similar replies predominantly from Ugandan users, demonstrates a recurring narrative that positions LGBTQI activism as foreign to African cultural values. One particularly hostile reply: “I thought it was [the] Zimbabwe government kumbe (or) these inhumans who aren’t normal,” highlights how opponents combine nationalism, moral panic, and dehumanisation to justify rejecting transnational LGBTQI solidarity efforts.

Some of the other comments on the post include:

- “You even want to also issue statement? What is really behind this LGBTQIA agenda? A pan-Africanist like myself is not taking it as face value. No. Something extremely anti-African is being promoted by the usual suspects.”

- “Sodom and Gomora were destroyed because of such unhuman acts, Why can’t you be normal and respect natural order that (sic) doing the acts that even dogs don’t do. Africa can’t not be destroyed by the acts of people who had lost moral and brains, we STAND WITH Uganda”

- “So funny these Confused ABC people 😂😏”

- “Dogs are better than this nonsense!”

- “Lgbtiq wateva u call urself pliz kindly leave our beautiful nation and go to the west where u r accepted. Isu muZim hatikudii….”

Screenshots of reactions to the GALZ post on X on 31 May 2023.

Backlash is not limited to regional political commentary but extends to direct hostility against local LGBTQI organisations. In June 2024, for example, GALZ suffered acts of vandalism and intimidation at its Harare office, as protesters defaced the organisation’s walls with slurs. “A group of individuals claiming to represent various Christian churches descended on our Harare centre, chanting slogans against homosexuality. They proceeded to vandalise the property, painting hateful graffiti on the walls,” it reported.

Homophobic graffiti sprayed on the wall outside the Harare offices of the Gays Lesbians Association of Zimbabwe (GALZ) by protesters in June 2024. Photo credit: @galzinf/X.

A job posting shared by GALZ on 25 June 2025 also attracted a mix of responses. WeGweru @Tinashe054 mocked the vacancy, asking: “Can non ngitos (homosexuals) apply?” while another user simply asked, “Is it remote?”

On 18 July 2025, a post about the launch of eMonitor Zimbabwe, a platform meant to track hate speech, received a positive response from LGBTQI supporters, but engagement remained low despite the initiative’s national relevance.

However, not all responses to LGBTQI issues reflect hostility; counter-narratives also emerge within digital spaces. In February 2024, the pro-LGBTQI account @verygayp challenged the Zimbabwean government’s criticism of LGBTQI-related scholarships, emphasising that GALZ is a legally registered institution and asserting that being gay is not criminalised in Zimbabwe. The reply reframes LGBTQI support as a legitimate response to socioeconomic marginalisation, attributing economic hardship to political misgovernance rather than sexual identity. This intervention demonstrates how activists strategically use legal frameworks and socio-economic arguments to contest state-driven stigmatisation.

Similarly, GALZ’s November 10 Facebook post documenting its engagement with national health institutions elicited positive reactions, suggesting pockets of growing tolerance. The post highlighted collaborative efforts with the Global Fund, the Ministry of Health, and the National AIDS Council, particularly around integrating Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics (SOGIESC) awareness into public health processes. The supportive comments, such as “GALZ Thumbs” and “Excellent Work”, indicate an emerging appreciation for community-led health initiatives and reflect a gradual shift in perception toward acknowledging LGBTQI organisations as legitimate stakeholders in national health governance.

GALZ’s 9 October 2025 pride-related Facebook post elicited predominantly positive responses, including expressions of regret about missing past events and aspirations for greater freedom of celebration. These engagements illustrate a counter-discourse that actively challenges claims that LGBTQI identities are Western imports. Nevertheless, dissent remains present, as evidenced by one user dismissing the post as “gay pride nonsense.” This mixture of acceptance and rejection reflects the contested nature of LGBTQI visibility in Zimbabwe’s social media landscape.

Across GALZ’s posts, one unmistakable trend is that while the organisation consistently communicates professionally and positively, reactions from the wider public remain either hostile or conspicuously absent.

Supportive comments on GALZ 9 October 2025 post on Facebook.

Strong Hostility towards UNDP’s Advocacy

UNDP HIV and Health @UNDPHIVHealth posted on 25 June 2025: “In Zimbabwe, #LGBTI+ communities face online hate and disinformation…” The tweet received 10 replies—all negative. Responses ranged from dismissive to aggressively hostile.

- “Please, take your evil, filthy doctrine to Ohio, not Harare.”

- “We have no LGBTQ community please.”

- “You are even committing crime by advocating such evil activity…”

- “I’ve never seen a gay person… So I come to conclusion that this LGBT is taught.”

- “We should… do what Arabs do to these less beings. Stone them.”

This concentrated hostility reflects the intense rejection that LGBTQI issues face when framed within international or institutional advocacy.

Reactions to broader international advocacy, however, also reveal subtle shifts in public sentiment. A 16 May 2024 UNDP X post emphasising global equality for LGBTQI people received an emoji response from a Zimbabwe-based account, suggesting tacit endorsement rather than overt hostility.

Massive Backlash against the U.S. Embassy

The United States Embassy in Zimbabwe’s Pride Month post on 1 June 2023 drew over 1,200 replies, with the overwhelming majority of them being negative. Comments included:

- “We will never celebrate people that confuse nature.”

- “This satanic agenda isn’t for Zimbabwe.”

- “Never allow westerners to dilute our African values…”

- “This is disrespect… Why is this embassy disrespecting our country?”

The scale and intensity of the criticism highlight the deep connection many Zimbabweans draw between homosexuality, cultural authenticity, and geopolitical resistance.

Mixed Reactions to Advocate’s LGBTQI Content

On 31 March 2025, feminist activist Tinatswe Mhaka (@tinathefeminist) posted: “Created a timeline on the history of homosexuality in Zimbabwe…”

The post attracted four replies, ranging from supportive: “So glad someone did the research for me!!” to downright dismissive, such as: “Of all the things you can write about or research about, izvi ndozvawaona zvakakosha? Nxa (this is what you found most important? Nonsense).”

The diversity of reactions reflected both curiosity and discomfort around discussions of sexuality, history, and identity.

Overall, the analysis reveals a digital environment in Zimbabwe where expanding LGBTQI visibility meets entrenched hostility, cultural defensiveness, and occasional, but still marginal, pockets of support.

While queer organisations have strengthened their presence and diversified their roles from health advocacy to rights-based mobilisation, public engagement remains largely polarised, with opposition fuelled by nationalism, moral panic, and the belief that LGBTQI identities are “unAfrican.” However, queer rights advocates like Dr. Stella Nyanzi argue the opposite: that homophobia, rather than homosexuality, is the imported concept, often reinforced through colonial-era laws and contemporary political rhetoric designed to consolidate power.

This article was produced with mentorship from the African Academy for Open Source Investigations (AAOSI) as part of an initiative by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and Code for Africa (CfA). Visit https://disinfo.africa for more information.