Despite decades of investment and expanded access to free treatment, Bulawayo’s health system is grappling with a silent but dangerous crisis with reports that between one percent and five percent of thousands of patients under antiretroviral therapy (ART) and Tuberculosis (TB) medication default.

Quarterly provincial review meetings and clinic audits repeatedly flag this trend, prompting the city’s health leaders to sound the alarm.

In an interview with CITE, Bulawayo’s Provincial Medical Director (PMD), Dr Maphios Siamuchembu said the trend is as baffling as it is dangerous.

“I would estimate between one percent and five percent of our patients, give us this problem. One thing that happens is people feel better and they think, ‘I don’t need to continue this treatment.’ But that’s not the case,” said Dr Siamuchembu.

“Patients think they’re cured” – the PMD’s warning

The PMD said treatment of TB takes a minimum of six months while treatment of HIV is lifelong.

“When you interrupt that, you’re basically culturing resistance and it comes back stronger then we have no arsenal to treat you,” he said.

“You get a patient who is admitted to Thorngrove Hospital, he has drug-resistant TB but then they abscond. They jump over the fence of the hospital, and they disappear.”

He said the health system itself is not blameless as it has limited security at facilities where some patients literally evade care, even though nurses make follow ups to patients’ houses.

“You enter the gate and they ask who’s there. You say, ‘it’s the health workers, we want to find out about your medicines.’ They say ‘wait for me outside, and then they jump the durawall,” he said.

“Some pitch up months later in a worse condition. And you wonder why people do that, because as far as we’re concerned, we’re trying to help them get better, and also to control that they don’t spread TB to other people.”

Dr Siamuchembu said defaulters often give false names, phone numbers and addresses.

“We call their phone numbers they’ve given us and it says this one does not exist. We follow up at the address and we are told, ‘we don’t know this person.’ Then we can’t find them, and we’re worried because this person is not on treatment. As you interrupt treatment, these diseases become worse. It’s a huge problem.”

A hidden threat amid years of progress

The PMD said, “I am not happy with any defaulter.”

“We want to treat everyone whom we can treat, cure them and make sure they don’t spread it. It’s the same thing with HIV, except that with HIV most of the time you have to consent to have sex and to get it. But with TB, you don’t have to do anything but be close to a person with TB. Even if you don’t know, you’ll get it. You see that?” said Dr Siamuchembu.

“We want to cut those numbers down. We want to get rid of TB and HIV, as public health concerns by the year 2030. We only have less than five years to do this. So we want to accelerate that.”

From United Bulawayo Hospitals (UBH) to Mzilikazi, Njube and Nketa, health workers are recording case after case of patients who vanish mid-treatment, often resurfacing only when critically ill or not at all.

In a recent provincial health TB review meeting in the first quarter of 2025 (Q1 2025), health officials admitted bluntly that they have “inadequate knowledge on factors contributing to high Lost To Follow-Up (LTFU) rate” so they must “conduct operational research on factors contributing to high LTFU in the city.”

Defaulting or being “lost to follow-up” (LTFU) in clinical language is not just a statistical headache but a threatening challenge that can undo hard-won progress in containing two of Zimbabwe’s deadliest epidemics – TB and HIV in Bulawayo.

Looking at minutes from quarterly provincial review meetings and clinic audits, here are some of the cases documented ‘when patients disappear.

From numbers to faces

The data from the quarterly provincial review meetings and clinic audits is not abstract. Individual stories illustrate the human cost.

At UBH, 25-year-old woman had been stable on antiretroviral therapy, but stopped coming for reviews after seven months. The staff tried to call her, then checked the address she had given but it drew a blank. Her file now reads: LTFU at seven months.

She is not the only one. In the same cohort, a 46-year-old man dropped out at month eight, and a 40-year-old woman at 22 months. All had given unreachable contacts.

At Nketa Clinic, a TB death audit was described as a “very ill patient… ART defaulter.” In other words, failing to take HIV treatment had left the patient fatally vulnerable when TB struck.

The data reviewed by CITE shows a persistent pattern across Bulawayo’s three administrative districts – Emakhandeni, Nkulumane and the Northern Suburbs, where clinic registers show loss to follow-up.

A glimpse of the data shows these are not isolated cases but are symptomatic of a system where patients slip through cracks.

Together, these records show a clear pattern, patients dropping out of either HIV or TB treatment in different clinics, over the years and across districts.

The broader epidemiological picture

According to the 2025 HIV Estimates Report for Bulawayo Metropolitan, as of 2024, an estimated 76 608 people were living with HIV in the province.

This represents a decrease from 79 711 recorded in the 2020 Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (ZIMPHIA), after calibration for more accurate population estimates.

Although this signals a cautiously optimistic outlook for Bulawayo, health officials continue to address challenges such as treatment defaulting and follow-up gaps that threaten to undermine these achievements.

Data from Mpilo Hospital (Jan–Aug 2025)

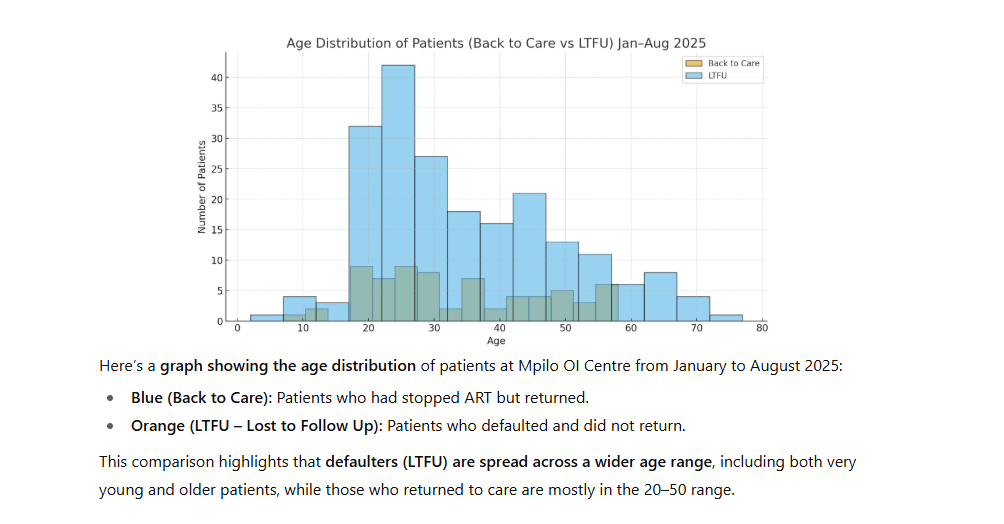

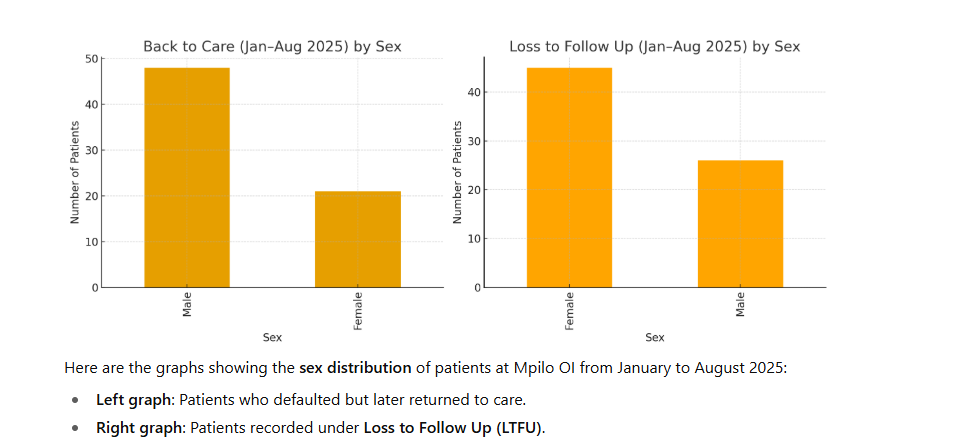

A fresh analysis of Mpilo Hospital’s outpatient infectious disease register for the first eight months of 2025 highlights a troubling divide in adherence to ART.

The data reveals stark differences between patients who briefly abandon treatment and those who disappear entirely from the system.

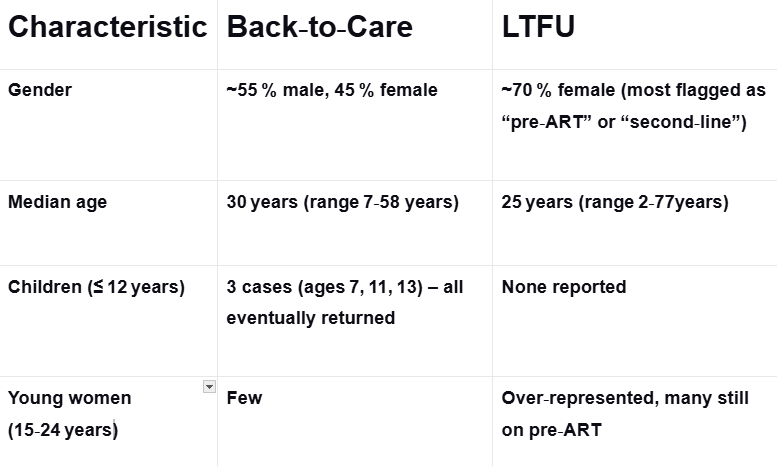

According to the hospital records, 73 individuals who missed appointments eventually returned to care, classified as “Back‑to‑Care.”

In contrast, 378 patients are listed as LTFU, having had no contact with the clinic for six months or more. For every patient who re-engages, more than five slip through the cracks.

The demographic profile shows a predominantly youthful cohort in their twenties, which may mean many are juggling school, work and family responsibilities alongside the demands of daily medication.

Gaps for back-to-care patients ranged from under a month to nearly four years, though 40 percent of returns occurred within six months of the missed visit.

LTFU gaps, by definition, exceed six months, a sizeable proportion extends beyond a year and a few cases stretch past three years, indicating chronic disengagement.

Short interruptions were far more likely to be resolved, while prolonged absences sharply reduced the likelihood of re-engagement, particularly for patients on second‑line or more complex regimens.

Most patients returning to care were still on first-line ART or were simply “taking pills elsewhere.”

Among those lost to follow-up, a significant number had already escalated to second- or third-line therapy, suggesting that even patients on more complex treatment plans are disengaging.

Several back-to-care records explicitly note temporary relocations to South Africa, Namibia, or other clinics elsewhere.

Mentions of “self-transfer” and taking “pills elsewhere” recur in both patient groups, underscoring a fragmented landscape in which patients drift between public and private providers.

Children appeared only among the back to care returnees, suggesting that caregivers eventually bring them back to care after, possibly after neglect, periods of lack of awareness or guardian change.

Young women dominate the LTFU pool, reflecting socioeconomic pressures, including transport costs, childcare duties and the need to earn a living, which pull them away from consistent clinic visits.

This Mpilo data paints a complex picture, reflecting that short-term treatment gaps can often be corrected, but prolonged disengagement remains a persistent challenge, especially among vulnerable populations.

The data also shows improved data systems, patient tracking and targeted support for high-risk groups will be crucial in reducing ART default and improving long-term health outcomes in Bulawayo.

Why patients default

In interviews as to why people default, one community elder in Old Lobengula, Giyani Moyo said, the major challenge was stigma.

“It’s because of stigmatisation at the point of collection of treatment tablets. It’s how staff say ‘abe TB wozani nga, abe HIV yanini le (TB patients come here, HIV patients go there,’” Moyo said.

“At clinics it’s prevalent, worse clinics have neighbours and friends also attending.”

A medical doctor said denial is another major reason why some patients default on treatment, as they struggle to accept their diagnosis.

The doctor, who requested anonymity, said his own brother was diagnosed with HIV in 2022 but defaulted on medication due to denial.

“In 2023, my brother left for South Africa, where his condition worsened. We later received a phone call from his friends informing us he was seriously ill. Since I am the doctor in the family, my relatives asked me to go and talk some sense into him,” he said.

However, when he arrived, his brother refused to resume treatment, insisting he only had isihlabo (pneumonia).

“Seeing how serious his condition had become, I arranged for omalayitsha (cross-border transporters) to bring him back home by force,” he explained.

The brother is now back on ART and picking up.

Economic hardships and Pill Burden

Charmaine Dube, who has worked extensively in HIV programming with various stakeholders in the district, said economic hardship and social realities are driving many patients off treatment.

“We have seen a lot of ART patients defaulting on their medication. Some of the reasons they are raising are pill burden, where someone just gets tired of taking the tablet every single day,” she explained.

“Other reasons are poverty, where people are struggling to make ends meet and to put food on the table. At times, a person will prefer not to take the tablet than to take it on an empty stomach.”

Dube said the withdrawal of USAID funding has also exposed serious gaps in Zimbabwe’s HIV response, particularly in urban districts disrupting service delivery and worsened structural barriers already facing people living with HIV.

“We saw some facilities that were offering express services closing down and people being referred back to public facilities, where there are longer queues. Most of the people are self-employed and prefer to rather go hustle than spend a whole day queuing for their medication. That has resulted in many defaulting,” she explained.

Read how – Bulawayo alone saw 53 HIV-related programmes shrink to just seven skeletal services after US funding cuts: https://cite.org.zw/67m-gap-threatens-zimbabwes-hiv-prevention-efforts/

Health system constraints, mobility and documentation gaps

Staff shortages in public facilities have also made the situation worse.

“The other reasons are the procedural delays people face. There are fewer nurses, so it takes much longer for a person to be attended to. Those frustrations are causing people to default on their medication,” Dube said.

On the other hand, medical staff suggest a mix of economic, social and psychological drivers behind the defaulting trend.

Sister in charge of the Opportunistic Infections (OI) clinic at Mpilo Hospital Centre of Excellence, Bongani Khumalo, says the centre currently serves 10 836 patients on ART.

“The most common reasons patients give for defaulting are people who go to South Africa in search of work and fail to get medications due to lack of legal documents, some give details that are not true, their phones are unavailable or it’s a wrong number,” he said.

“Adolescents struggle with adherence despite counselling, pill fatigue, lack of disclosure to partners, especially in new relationships, and mental health issues. Others tell you they had no transport fare.”

From his observations, the crisis has a youthful face and also cited how stigma remains a persistent factor.

“Some youth or teenagers have been taking ART for their whole life since birth and are now fatigued,” Khumalo said.

Stigma and discrimination

Meanwhile, some patients avoid clinics because they fear being recognised by neighbours, said Moyo, the community leader.

Others conceal their status from partners and families, leading to hidden struggles with adherence.

This was corroborated by National AIDS Council (NAC) provincial manager, Sinatra Nyathi, who said stigma and discrimination continue as a problem.

“We do have the stigma index report, which talks about where we are in terms of stigma and according to the current report, we are not going down in terms of stigma, but actually going up,” she said.

A 2022 report, the Zimbabwe People Living with HIV Stigma Index 2.0, revealed that despite major progress in HIV treatment access, stigma and discrimination remain widespread.

The study, which was cross-sectional and conducted in all Zimbabwe’s 10 provinces with 1 400 participants found that the most common forms of discrimination faced by people living with HIV (PLHIV) include:

- Exclusion from social gatherings

- Gossip

- Verbal abuse

- Physical abuse

Stigma was reported across multiple spaces, including families, health institutions and communities.

At the same time, the report indicated Zimbabwe has made remarkable strides in treatment, with close to 100 percent of respondents reporting access to HIV care services, noting strong resilience among PLHIV, which is vital for their physical and psychological well-being.

“Looking into the future, HIV programming in Zimbabwe should prioritise creating an enabling environment to reduce stigma and discrimination against PLHIV to sustain and enhance their health outcomes and quality of life,” the report concluded.

Danger of defaulting

The NAC provincial manager said there was a huge danger of defaulting.

“You need to understand that HIV attaches itself to your T-helper cells in order to infect you. If that attachment doesn’t happen, infection cannot occur. That’s why studies have shown that some people with certain cell deformities are resistant to HIV, it simply cannot attach. This is also how ARVs work,” Nyathi said

“Different ARVs target different stages of the HIV life cycle. Some prevent attachment, like in PEP, which is given soon after possible exposure to stop the virus from entering the cells. Others target multiplication inside the cell, preventing the virus from bursting out and spreading. These drugs are specialised to fight HIV. That’s why we use a combination of three drugs -to block HIV at multiple points.

“If you stop treatment, you give the virus a chance to multiply quickly and attack more cells. That’s when it becomes dangerous. Many people stop treatment, feel fine for a while, then return when it’s too late. The virus will have multiplied, invaded more cells, and often mutated. HIV mutates very fast, and once it changes, the drugs you were taking may no longer be effective.

“That is why adherence is critical. Staying on treatment keeps the virus suppressed and gives you a much better chance of living a healthy life.”

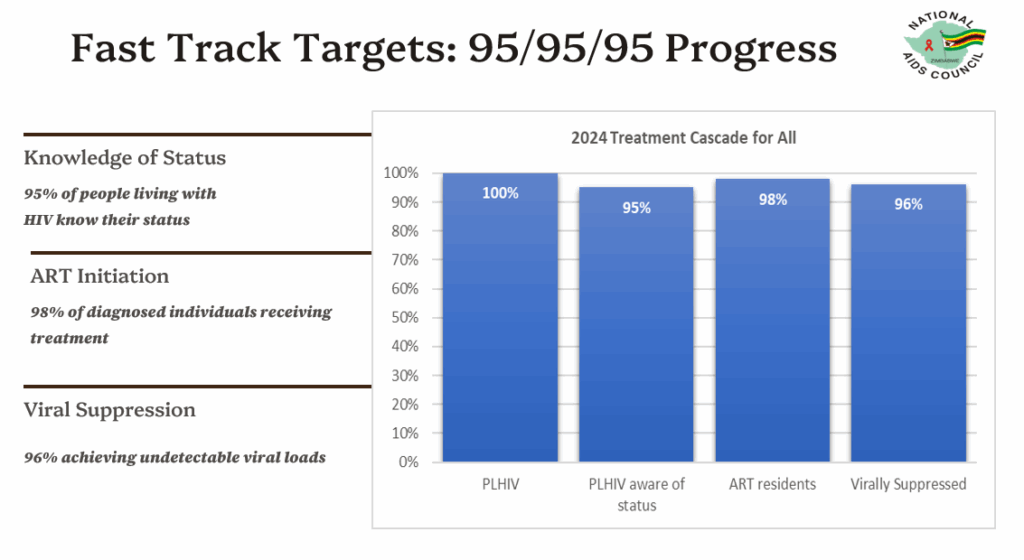

According to the 2025 HIV Estimates Report for Bulawayo Metropolitan province, looking at the treatment progress, 95 percent of people living with HIV know their status, 98 percent of those who know their status have been initiated on ART.

Among those on ART, 96 percent have a suppressed viral load.

Viral suppression remains a challenge, largely due to poor adherence, according to Mpilo Hospital’s Centre of Excellence medical director, Dr Nkazimulo Tshuma.

Dr Tshuma said starting a patient on ART does not automatically mean their viral load will be suppressed.

“We can give one medication, but it is now up to the patient whether they take it properly or not.”

She pointed to several factors that contribute to inconsistent medication intake.

“There are issues drug to drug interactions some people have different books when they come to us they don’t tell us they have other conditions and we wont know they are on other medications so ARVs can also interrupt with other medications that they are taking causing them not to suppress the HIV properly, that is one of the reason why people are not suppressing their load,” Dr Tshuma explained.

However, Dr Tshuma stressed that the main reason remains poor adherence.

“People are not taking medicine properly because of many other factors. We know generally we are all undergoing challenges here and there, some people when they go through challenges, tend to stop taking medicines,” she said.

Dr Tshuma said while health facilities are performing well in terms of ART supply and record-keeping, achieving viral suppression requires more than providing medication.

“So medicines are being supplied, interestingly, those people come for their reviews, monthly or every six months or they collect but keep them at home. In terms of us supplying ART record wise we would have done very well but come to viral suppression, sometimes we are not doing so well,” she said.

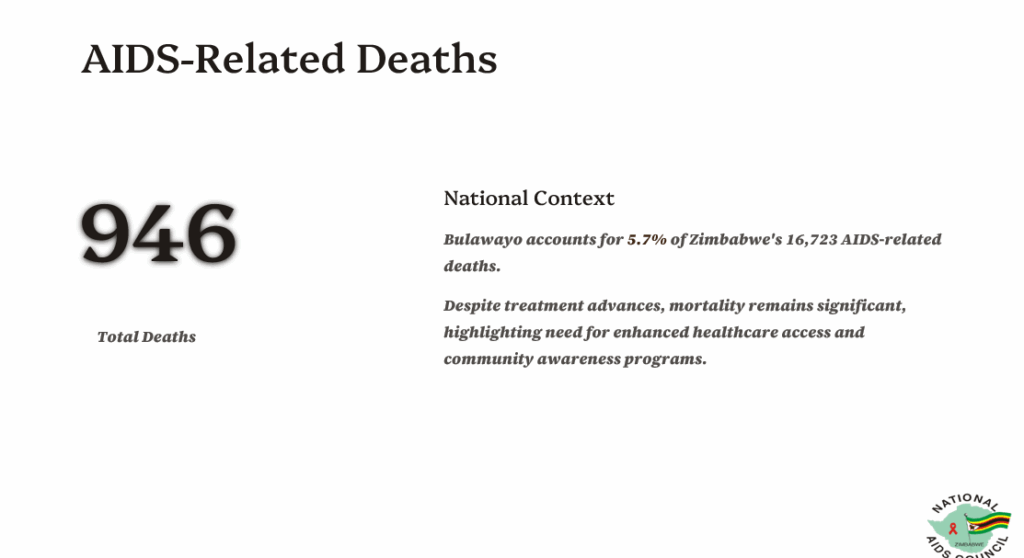

The 2025 HIV Estimates Report for Bulawayo Metropolitan Province shows that the city continues to bear a significant portion of the national burden of AIDS-related deaths.

According to the report, approximately 946 people living with HIV in Bulawayo died from AIDS-related causes in 2024.

The city’s figures represent 5.7 percent of Zimbabwe’s total 16 723 AIDS-related deaths recorded nationwide during the same period.

Adherence push

Ward 26 Councillor Mpumelelo Moyo, interviewed at a mobile clinic in Emganwini, warned that men who default on HIV and TB treatment are putting their own lives and the wellbeing of their families at risk.

“Men default because naturally they are risk takers, but where they take risk is a danger to their lives,” Moyo said.

“They should be continuously educated on the importance of taking medication. For TB, one must take pills until the course is completed, and for HIV, pills are taken for life. Men must realise it’s their health that is at risk, and stopping treatment could leave their families vulnerable.”

The councillor highlighted his role in encouraging adherence.

“It is my responsibility as a councillor to encourage men wherever I go to take pills continuously, not to default and be there for their families,” he said.

The PMD, Dr Siamuchembu also warned on how defaulting is a “big problem” particularly for TB.

“If I am on treatment and default, I develop TB resistance, which I can give to you. The person infected doesn’t have to do anything but just has to be close to me to get TB. We then end up spreading a drug-resistant TB, which we can’t afford. This is a problem for the country because we will not be able to contain it,” he said.

Emerging solutions

As a response, hospital staff at Mpilo said they are updating record keeping systems and the rollout of an electronic health-record (EHR) platform is expected to improve tracking across facilities, flag duplicate prescriptions and support patient retention for those who move between clinics.

Health authorities said they were also pushing differentiated service delivery (DSD) models to reduce barriers but this has been affected by the foreign aid funding cuts.

Under this model, families were allowed to send one member to collect ART for everyone.

In some rural areas, patients linked to Community ART Refill Groups (CARGS) took turns collecting for each other.

In cross-border communities, the malayitsha system evolved where these informal transporters ferry both goods and medical records between Zimbabwe and South Africa, collecting ART on behalf of patients working in the diaspora.

“The malayitsha is also taught how to maintain those drugs, make sure they are packaged well. It’s very safe,” Nyathi said.

NAC Programmes Officer, Douglas Moyo, said the fact that omalayitsha were organising themselves and taking turns to collect medication shows real commitment.

“They have sustained that arrangement for a long time. If you want to see the success of the omalayitsha system, go to Tsholotsho rural clinics. Most of their clients are actually in Botswana and South Africa, not in the villages. It’s a very successful model, though not well documented and it’s proving to be very effective in rural areas, even in places like Plumtree.”

Despite these innovations, staff acknowledge gaps and funding challenges.

Follow-up systems often fail once patients give false addresses and mental health services remain thinly stretched, leaving many untreated for depression and substance abuse, both linked to defaulting.

Khumalo said the OI clinic tries to cushion patients with support groups, peer counselling, telehealth, free lab services and even cervical cancer screening.

“To keep patients on ART we must provide individualised care, address client concerns, and monitor progress,” said the sister in charge.

Dube, a health advocate, concurred community engagement and support groups are critical in keeping patients on track.

“There should be strategies like community support groups, where people are encouraged and empowered to take up their health more seriously,” Dube explained.

“Traditional methods where people have been grouped in groups of 10 or 20, maybe it’s an ART or TB support group where those recipients of care, share experiences of what they are facing and how they are tackling challenges and encourage each other to continue taking up health education also work.”

Dube also highlighted the importance of addressing nutritional challenges that often affect adherence.

“We have also opted that people don’t focus on the most expensive food but the basics like umfushwa, which is more accessible,” she said, adding that “growing gardens at the back of their homes so they get something to eat as much as they are facing economic challenges,” helps people stay on treatment without compromising their health.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today

This is very informative. It’s good to know how much work is being put into HIV care, treatment and prevention. Salute to all the health workers and the journalist who wrote this article. Despite the challenges people face, different institutions and health workers are doing their best. People need to be sensitized about the implications of defaulting.