For many young Zimbabweans, securing a place at university is a dream. But for students with disabilities, that dream often comes wrapped in layers of obstacles from a shortage of lecturers able to meet their needs to the absence of adequate learning materials in accessible formats.

Although some advocates acknowledge improvements in the enrolment of persons with disabilities (PWDs) at tertiary institutions, many stress that progress has been slow and uneven.

They warn that without deliberate policy action, thousands of capable students will remain locked out of higher education opportunities.

In 2022, the Deaf Zimbabwe Trust reported that statistically, less than three percent of PWDs had access to higher education.

The organisation noted that access to tertiary education is directly linked to access at lower levels, highlighting the need for a robust, inclusive education policy.

A situational analysis by the United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNPRPD) in 2022 painted a similar picture, finding that the absence of comprehensive inclusive education policies has resulted in high levels of inaccessibility for learners with disabilities.

The report emphasised that the lack of coordination between the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) and the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education hinders knowledge sharing and continuity of support for PWDs transitioning through the education system.

“Special schools are still the main education institutions for children with disabilities, those who are fortunate or have resourceful parents. The generally low quality of the public education system makes it difficult to envisage how and when inclusive education could become a reality. The lack of linkages between MoPSE and the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, and the absence of a platform for knowledge sharing, is a key challenge,” the report stated.

CITE spoke to disability rights advocates who outlined several gaps in the tertiary education sector that must be addressed to effectively implement inclusive education.

Disability Development Consultant, Tsepang Nare, said one of the major challenges in tertiary institutions is the shortage of lecturers who can deliver lessons in sign language.

“Lecturers and teachers at tertiary institutions are not capacitated to deliver lessons in sign language. English is often prioritised as a spoken and written language, but sign language, an expressive language using gestures, facial expressions, and incorporating deaf culture, is not recognised as part of the requirements for enrolment at tertiary institutions. That becomes a major barrier,” he said.

Nare added that partially deaf students who manage to pass English still face challenges, as most institutions do not provide sign language interpreters.

“In many cases, students must hire their own interpreters on top of paying tuition fees. Learning materials are also predominantly in written text, which is different from sign language and more difficult for deaf students to comprehend,” he said.

He commended organisations that have partnered with tertiary institutions and the government to improve access for PWDs, but said more needs to be done.

“There is a need for awareness and sensitivity among lecturers and students on issues of sign language. Disability studies as a module is not yet compulsory, and there are no mandatory refresher courses for lecturers,” Nare noted.

Robert Malunda, founder and director of Gateway to Elation, an organisation that supports visually impaired people, applauded government and institutional efforts to increase enrolment of PWDs. He cited initiatives such as the University of Zimbabwe’s Vice-Chancellor’s Scholarship for persons with disabilities and government tuition assistance for blind students.

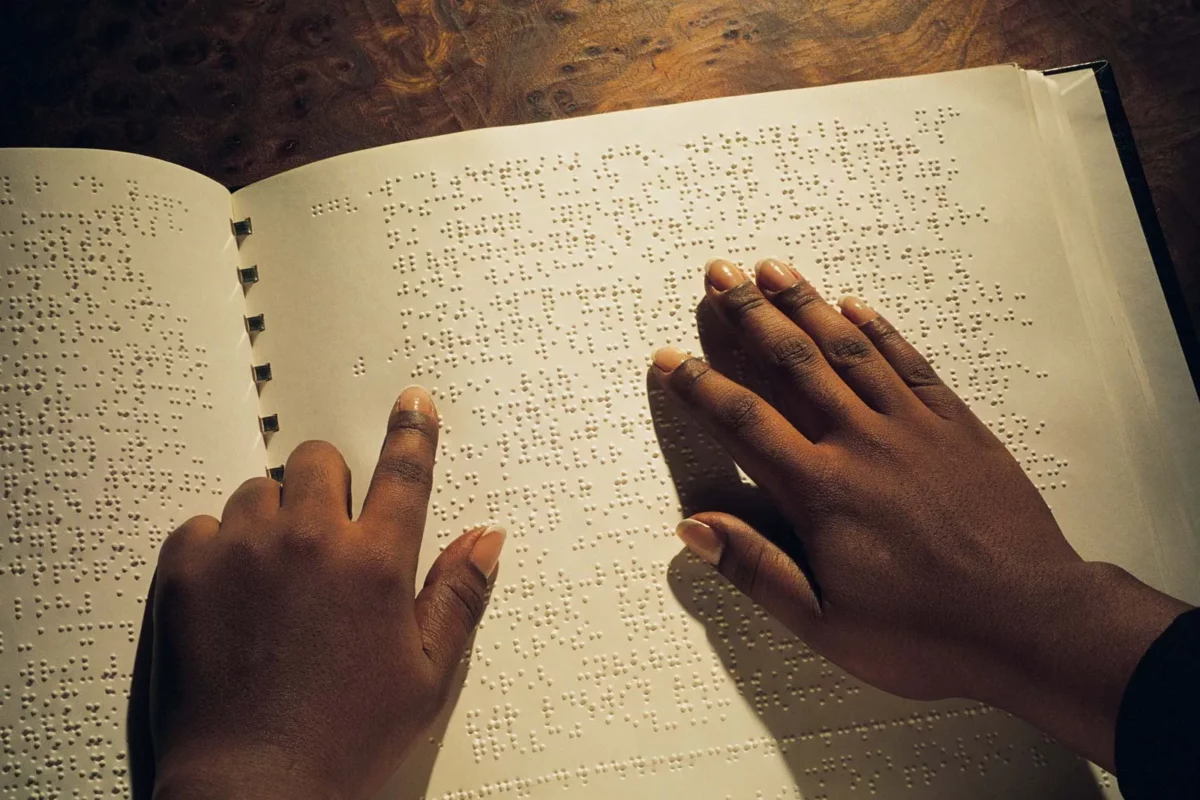

However, Malunda noted that access to information remains a major barrier. “Braille equipment is still scarce, yet Braille promotes proper literacy for the blind and strengthens written communication skills. Screen-reading software and audio should complement, not replace, Braille,” he said.

He also pointed to disability-based stigma as a significant challenge in tertiary institutions, which often leaves visually impaired students socially isolated.

A special education teacher who spoke on condition of anonymity said inclusive learning requires teachers trained to cater for all learners.

“Sign language is a full language with its own expressions and structure. Teachers must know how to simplify concepts for students who use sign language so all learners are catered for equally,” the teacher said.

Senator Anna Shiri, President of the National Council of Persons with Disabilities, urged relevant ministries to prioritise inclusive teacher training in sign language and Braille, in line with constitutional and international obligations.

“Section 75 of the Constitution guarantees the right to basic education, while Section 83 mandates the State to provide special facilities for learners with disabilities. Zimbabwe has also ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and launched the National Disability Policy in 2021,” she said.

Sen Shiri called for budget allocations to upgrade school infrastructure, provide assistive technologies, and train teachers in inclusive pedagogies.

“We must expand digital inclusion by integrating assistive ICT solutions and partnering with mobile networks to connect rural inclusive schools,” she added.

Support CITE’s fearless, independent journalism. Your donation helps us amplify community voices, fight misinformation, and hold power to account. Help keep the truth alive. Donate today