With community hearings into the Gukurahundi atrocities underway across Matabeleland, the government’s recent pledge to compensate victims has stirred mixed feelings among survivors and their families, with many questioning its timing, sincerity and practicality.

The National Council of Chiefs said compensation would be case-specific and depend on the unique experiences of each individual or family affected by the 1980s genocide.

However, at Khozi Village in Ward 6, Gwanda North, where community members gathered for hearings led by Chief Mathema, locals expressed conflicted sentiments over the government’ proposed redress.

In seperate interviews after the hearings which CITE did not attend as stipulated by the National Chiefs Council, some said compensation might bring a sense of relief, but others felt that no amount of money could undo the pain or bring back the dead and that what they wanted most was a “sorry” from the perpetrators.

“Compensation is tricky,” said one villager who asked to remain anonymous.

“Yes, it may lessen the burden we’ve carried for decades. But the real people who suffered, those tortured and killed, are buried under this soil. If only the perpetrators had come and said ‘we are sorry’ while still alive, it would have meant more. Now we just hear rumours about compensation. Nothing is in writing. How much? Who qualifies? We don’t know.”

The survivor added that, after 42 years, many victims are now elderly, some crippled and unwell. “Even if you get money now, will it really help? No one knows,” said the villager.

Another villager used a stark analogy to express discomfort about the meaning of compensation.

“Yes, we can talk about compensation but how will I describe it?” he asked.

“Let’s say I catch someone with my wife and he pays me two cows as a fine. What do I call those cows? ‘Cows for adultery?’ How do I explain what this money is for, people being killed?”

For him and others, a simple apology would go much further.

“It’s better for sorry then it ends like that. Even in families, when there’s a conflict, it’s the word ‘sorry’ that is important,” he said.

Another community member doubted whether the government could deliver on its promise at all, given its poor track record with war veterans.

“When we talk about compensation, remember the government has failed to compensate those who helped liberate this country. How then can it compensate people it actually intended to kill? They sent people to carry out the killings, and now they say they want to compensate us, the very victims of that plan,” said the member.

“People were arrested at Gonakudzingwa simply for wanting to liberate this country. Some went into exile, some picked up arms, others played different roles yet many of them have never been compensated. Now the same government says it will compensate us, the people it gave orders to be beaten and killed. How does that make sense?”

This community member recalled a chilling meeting in the 1980s where a top government official, the late Enos Nkala, allegedly told military commanders not to maim but to kill.

“One meeting, I recall Enos Nkala asking us who had broken limbs after the attacks to lift our hands. He called the head of the army and asked what they were doing, breaking people’s limbs, yet he had said they should come and kill, not to leave people with broken limbs,” he said.

“Because breaking only our limbs meant we were left alive, not dead. What was said here during that time was too bad.”

The member added that is why they waited here for the chief to come so we can talk about it.

“Even the chief knows what happened because he was there when people were thrown into a hole. I don’t think we can cry for compensation for acts they did by sending people to kill us.”

He continued: “I was born in 1946, went to war in 1977, came back in 1980, and was attacked in the 1980s. I lost children. Others are still missing. If they give me money, how do I describe that compensation?”

Among those who attended the hearings was a 76-year-old Gukurahundi survivor who had been detained for 11 months in 1984.

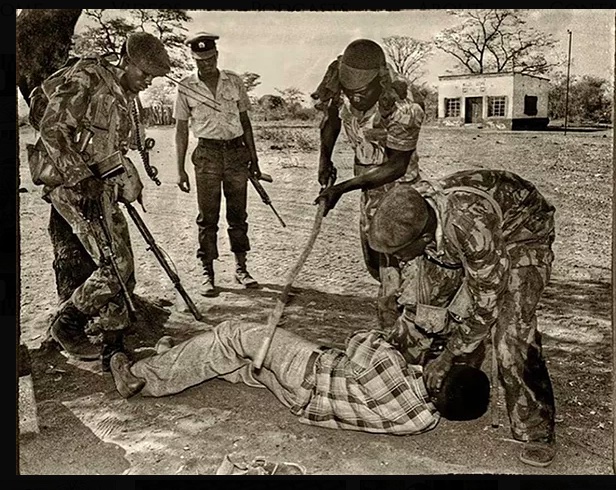

He said he was held in Matopo, Gweru, Bhalagwe, and Harare, experiencing brutal torture, including electrocution and beatings that left lasting damage.

“I was arrested in February and released only on December 28,” he said.

“I was a ZPRA. I was trained in Zambia and was working in Mbudzi in Mutoko and when Gukurahundi caught me in 1984 was coming home for off days.”

Now frail and unwell, he said he had suffered permanent injuries.

“My eyesight and hearing is poor. They beat me under my feet with planks and screws. They used fire to burn and swell my legs. I couldn’t walk. had to be carried. I wasn’t even married then, just had one child. I wondered if I would have more. Even today, I keep my shoes on because my feet still hurt. The original skin was burnt off.”

While he welcomed the hearings, he insisted on the need for monetary compensation, even if delayed.

“What is the cost of my lost freedom? I should have been working, building my life. I can’t say how much I deserve. They plotted Gukurahundi knowing there could be consequences. They should take responsibility.”

He also said the panel appeared genuine, even requesting to photograph his scars for documentation.

“They seem serious about their work. Maybe something will come of it. If there’s to be compensation, it must be real, swift, and sincere.”

The Gukurahundi community hearings are being led by traditional chiefs with support from local panels comprising elders, youth, women, counsellors and religious leaders. The process seeks to provide platforms for survivors and communities to share their experiences and guide national reconciliation efforts.

At CITE, we dig deep to preserve the stories that shaped us—ZPRA Liberation Archives, the DRC War, and more. These are not just stories—they’re our roots. We don’t hide them behind paywalls. We rely on you to keep them alive. Click here to donate: https://cite.org.zw/support-local-news/