Reginald Mkhosana and his subjects from St Peters village on the outskirts of Bulawayo are classified as urbanites in terms of Zimbabwe’s political boundaries, but their living conditions undoubtedly mirror the penury that typifies rural life.

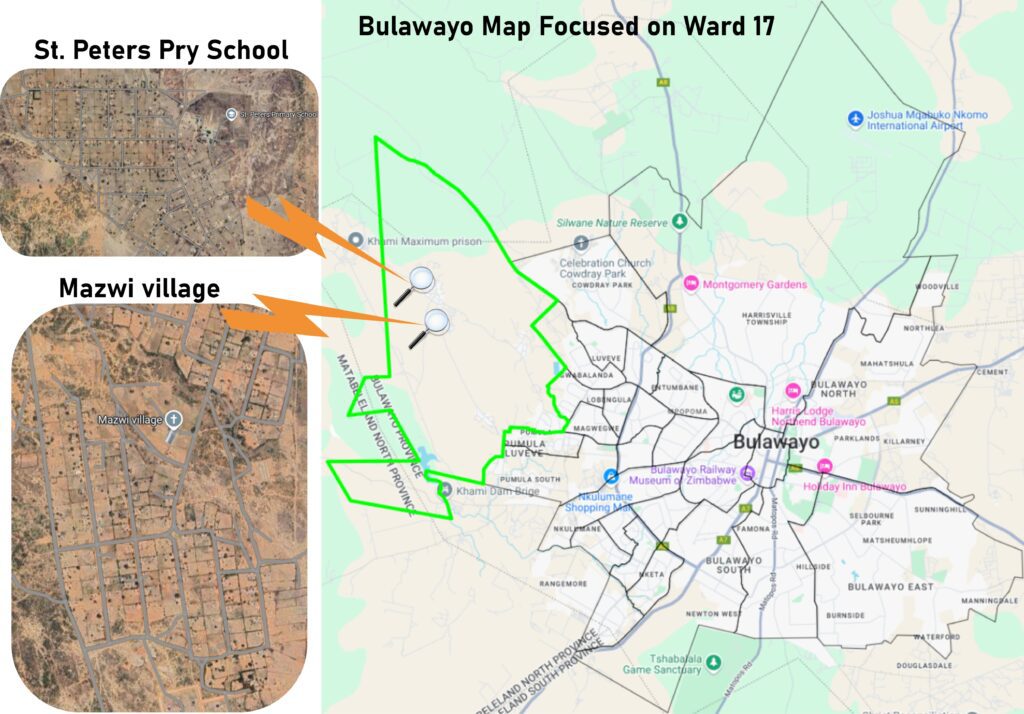

St Peters like Robert Sinyoka, Mazwi, Hyde Park Estate and Methodist villages are under Bulawayo City Council’s ward 17 and are part of Pumula Constituency that also encompasses Old Pumula, Pumula North and Pumula South high density suburbs.

Lying on the fringes of Zimbabwe’s second largest city, the five villages have been partially assimilated into the boundary of the greater Bulawayo urban space, but the areas are disconnected and marginalised from the sites of business and commerce in the city.

There is a distinct difference between the urban areas of the city and the villages that accommodate the poor and the marginalised where the majority still live in mud huts without running water and electricity.

Mkhosana, who is the village committee chairperson, said they still walk distances of between five and 12 kilometres to access primary health care services because of the slow pace of development in the area.

The roads in the village are not navigable and access to running water is still a pipe dream for the majority while infrastructure at the local school is crumbling due to years of neglect.

“We don’t have a clinic and the situation is very bad,” Mkhosana told CITE at his homestead in St Peters.

“People walk to Pumula Clinic, which is 12 km away, for treatment or go to Khami Clinic that is 5km from here.

“The city centre (where there are referral hospitals) is about 27 km from where we stay.”

The villages are mostly made up of people that lived under constant threat of displacement by various local and national authorities before they were formally resettled by the government before independence.

Some came from informal settlements within urban Bulawayo such as Ngozi Mine and Killarney.

Information obtained from the Bulawayo City Council shows that Robert Sinyoka Village has 107 households, Methodist Village (110), St Peters Village (188) and Mazwi Village (197).

Pumula Constituency where the villages are located is a largely urban administrative area politically, but the settlements are disconnected from services found within greater Bulawayo.

An investigation by CITE in collaboration with the Information for Development Trust (IDT), a non-profit media organisation promoting investigative journalism in Zimbabwe and the SADC region, revealed a wide urban and rural divide in the constituency that put the struggles of villagers in the five settlements into sharp focus.

Lagging behind

Ideally, the pace of development at St Peters, Robert Sinyoka, Methodist, Mazwi and Hyde Park Estate must be at par with what is happening in the urban parts of the constituency as the villages are officially under the Bulawayo City Council.

The areas should also be benefiting equally from the council’s ward retention fund and Parliament’s Constituency Development Fund (CDF), but the villagers say they are not seeing the impact of both schemes.

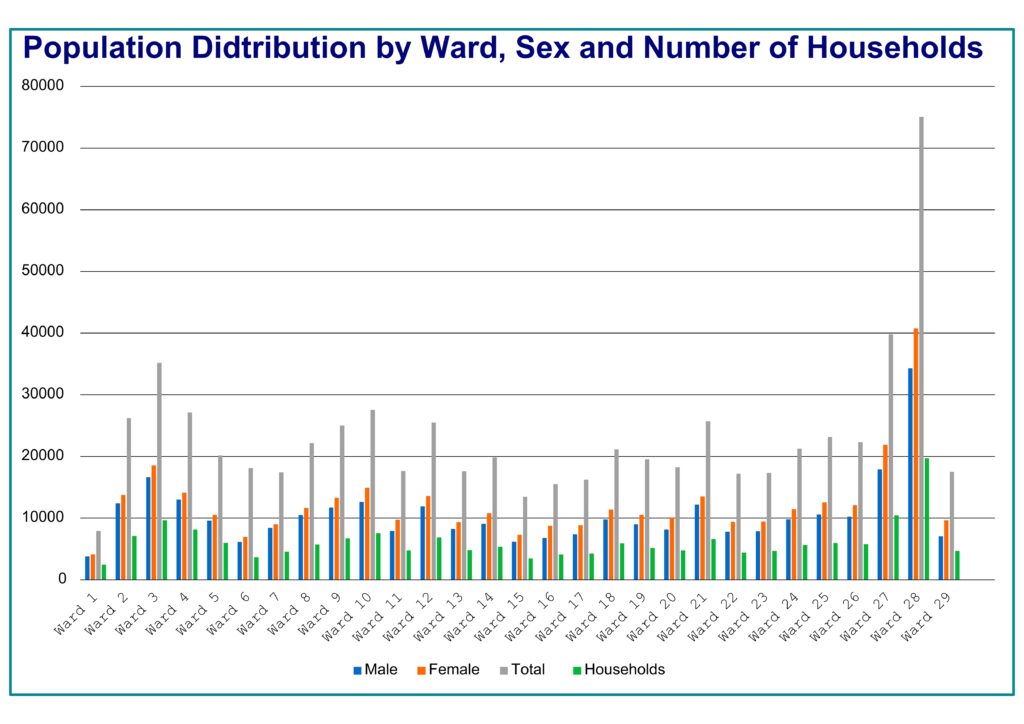

Council through its ward retention policy allows its 29 wards to retain three percent of the rates residents and businesses pay to the local authority for the development of their areas.

Councillors are the custodians of the funds. On the other hand, the government introduced the CDF in 2010 to enable legislators to spearhead development projects in their constituencies.

MPs get up to the equivalent of US$50 000 a year from the CDF, but the scheme has over the years been disrupted by Zimbabwe’s currency problems.

The allocations, which are often in local currency, are disbursed late to an extent that by the time they become available to the constituency the money would have lost value significantly.

In April the country switched to the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) from the RTGS dollar after the local currency was battered by inflation. This was despite the fact that this year’s national budget was crafted in RTGS.

Zimbabwe has been battling currency instability since 2008 when it dumped the inflation ravaged local currency in favour of multicurrencies dominated by the US dollar. The local unit was reintroduced in 2019, but it has struggled to find its footing on the market.

Over the years, legislators have been pushing the government to disburse the CDF money in US dollars after service providers rejected the unstable local currency.

MPs always attribute their failure to complete projects or to initiate new ones to late disbursement of funds and currency fluctuations.

Mkhosana, the St Peters village leader, said development remained elusive in his community as he bemoaned the lack of a clinic in the area and a deteriorating road network as well as a shortage of well-equipped schools.

Situation dire for villagers

The five villages suffer from perennial water shortages as the homesteads do not have running water.

They rely on water points that consist of taps dotted around the villages and council insists that it has no capacity to provide running water in their areas because of dwindling supplies and lack of funds to improve infrastructure.

Bulawayo is battling perennial water shortages because of a population that has outgrown the six supply dams and the effects of climate change.

*Video of the woman opening a tap*

Four of the city’s supply dams were built before Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 when Bulawayo’s population was 386 000.

The 2022 national census put the city’s population at 658 028. Council has in recent months stopped drawing water from Umzingwane and Upper Ncema dams after they ran dry due to the drought.

Bulawayo also gets some of its water from boreholes on the Nyamandlovu Aquifer, but supplies remain way below the daily demand of 135 megalitres a day for the city.

“We also have a challenge with water as the pipes are now old and are small,” Mkhosana said.

“They can no longer adequately serve the growing population in this area.”

Saliwe Ngwenya from Mazwi said the lack of health facilities in the area was a sign of under development, which put people’s lives at risk.

“The only time we get health services closer to us is when staff from Pumula Clinic carry outreach activities such as the immunisation of children,” Ngwenya said.

“At times when we call for ambulances to rescue women who are labour they take too long to arrive because of the poor road network and this gives rise to home deliveries.

“We are appealing for a clinic to be built here so that we can access health services.”

Phathiwe Tembo, who said her family was resettled in Robert Sinyoka in 1969 from an informal settlement that was in the Pumula area, said the village had seen little development despite its proximity to Bulawayo.

“The local roads are in a bad state,” Tembo said. “When we call for an ambulance during an emergency they can only drive to a certain point and we push the sick person in a wheelbarrow to reach them.”

Tembo said villagers have to wake up as early as 4am to fetch water at designated points and this posed serious risks, especially for young girls who were susceptible to attacks by sex predators.

The villagers rely on a few community boreholes dotted around their areas. Their livestock also gets water from the boreholes as there are no dams in another sign of underdevelopment.

NGOs to the rescue

Mkhosana said the only institutions that have shown interest in developing their area were non-governmental organisations that assist them to set up horticulture gardens.

“The pace of development here is very slow compared to the urban areas,” he lamented.

“We are peasant farmers and as such most people are unemployed and our only source of development is non-governmental organisations, who help us with gardening projects, among other things.”

World Vision, one of the NGOs that was supporting the Robert Sinyoka community with development programmes targeted especially at children and “offering relief to elders in the village” for 23 years, pulled out on August 7 this year, council documents showed.

The humanitarian organisation constructed two teachers’ cottages at St Peters Primary School to curb the problem of high staff turnover.

It was also part of a consortium of organisations that established Sizalendaba Secondary School and also supported other schools around the area.

“The City of Bulawayo is grateful for the assistance rendered by the World Vision organisation through its interventions to the underprivileged and disadvantaged communities in and around Bulawayo Metropolitan Province,” reads a report of council’s health, housing and education committee tabled at the local authority’s full council meeting in early October.

“It is hoped that in future they would return and continue being a worthwhile partner of the City of Bulawayo,” the local authority added.

Bulawayo United Residents Association chairperson Winos Dube said the lack of development in the peri-urban villagers was a major source of concern.

Dube said a shortage of facilities such as clinics was worrying and urged the community to continue putting pressure on the authorities until they act on the uneven development of the ward.

“The villages depend on Pumula Clinic as they do not have any facility close to them,” he told CITE.

“Those people need to be taken care of and the authorities must make sure that there is a clinic close to them, which is very important.

“Local authorities will always cite various challenges for failing to provide services, but there is need for these peri-urban areas to have clinics close to them.”

One of the Mazwi villagers, Margret Mpofu (70), said she had been struggling to access treatment for a suspected hip fracture for over two weeks because she had no money for transport to the nearest clinic.

“I got injured two weeks ago on my hip after I fell while coming from fetching water,” Mpofu said. “I don’t have money to go to Pumula Clinic or the one at Khami Prison.”

She said one of her grandchildren, who always ferries her to the clinic on a wheelbarrow, was away.

No schools, no hospitals

Nqobizitha Moyo, the Bulawayo Progressive Residents Association (BPRA) organising secretary for ward 17, said people living in the villages on the outskirts of the city were bearing the brunt of lack of facilities such as hospitals and schools.

Moyo said they have been pushing for the construction of clinics and schools in ward 17 to alleviate the suffering of villagers, who have to walk several kilometres to access health services.

“The people in ward 17 have to walk to Khami Prison to access primary health care services,” he said.

“Some residents use scotch carts while others walk to a clinic in urban Pumula and they would be struggling due to illness.

“As BPRA we have been advocating for the construction of a clinic near Sizalendaba to serve all the four villages and this will alleviate the problem of people having to walk several kilometres to access primary health care services.”

Moyo said they were organising regular meetings with residents and other stakeholders to plot the effective use of the ward retention fund, including the construction of a proposed clinic to service the areas.

Waiting for city to expand

Ward 17 councillor Sikhululekile Moyo said the villages were being serviced by a mobile clinic and more services would become accessible as the city expands.

The councillor said ward retention funds had been used to develop the Robert Sinyoka football and netball fields and there were plans to also develop a water reticulation system in St Peters as villagers there had no access to running water.

For this financial year, Ward 17 was allocated US32 299 and $ 444 306 in local currency under the ward retention fund, information obtained by CITE indicated.

Some of the projects that have been proposed for next year to be bankrolled by the fund include rehabilitation of streetlights on the urban side and construction of a car park at the Pumula North municipal hall.

The five villages will benefit from the construction of staff cottage and a science laboratory at Sizalendaba Secondary School.

The councillor said they were pinning their hopes on plans to expand the City of Bulawayo by a radius of 40 kilometres as proposed in the local authority’s new masterplan. Expansion of the city’s boundaries will see the five villages being formally incorporated to spur development.

Sichelesile Mahlangu, the Pumula Constituency Member of Parliament from the opposition Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) , said constant recalls of elected representatives and currency instability was impeding the effective use of the CDF.

Pumula has been under control of the opposition MDC, MDC Alliance and now CCC since the year 2000.

Since the CDF was introduced in 2010 there have been three recalls of MPs representing the constituency because of perennial squabbles afflicting the opposition.

Mahlangu said they have tried to spread the funds to finance projects in the constituency’s three wards, but bemoaned the low allocations.

“Pumula has three wards, which are 17, 19 and 27,” she said. “Ward 17 encompasses the rural villages.

“The first CDF allocation of $50 000 (in local currency) was used at Methodist Village at a school called Hyde Park where we renovated an ECD (early child education) block.

“We had to start with the rural side because we felt that the school was left behind in terms of facilities.”

Mahlangu said they were yet to get allocations for 2023 and this year, which they had budgeted for the construction of a community hall at Robert Sinyoka.

She said the community’s expectations were too high because they believed that the CDF allocations were in foreign currency, which was not the case.

The MP said there was need to treat the urban and rural sides of the constituency equally as she admitted that the five villages were marginalised.

“Development must be equal, but this is not the case at the moment because the road network on the rural side of the constituency is poor,” Mahlangu said.

“The Khami Prison road is in a poor condition and as the MP I want to see it being upgraded so that there is development.

“The council also needs to rehabilitate the community water points so that the people in the villages enjoy their rights to water as guaranteed in the constitution.”

She said there was need for cooperation between national and local government representatives to push for development in the marginalised areas.

Council spokesperson Nesisa Mpofu said council’s vision for residents to have clinics within where they lived was being hampered by lack of money for infrastructure development.

“There are plans to ensure all citizens have a clinic within walking distance (of at least 5km),” Mpofu told CITE.

“However there is a challenge of staffing and low capital budget funding.”

Bulawayo, like most local authorities in Zimbabwe, have been failing to embark on meaningful capital projects over the last two decades due to a failing economy and currency problems.

The local authority has budgeted US$82 million for capital projects next year yet according to the mayor David Coltart the city needs a minimum of US$15 million to maintain its road network alone.

Central government is also accused of taking too long to approve the council’s annual budgets, which slows down collection of revenue that goes towards the ward retention funds.