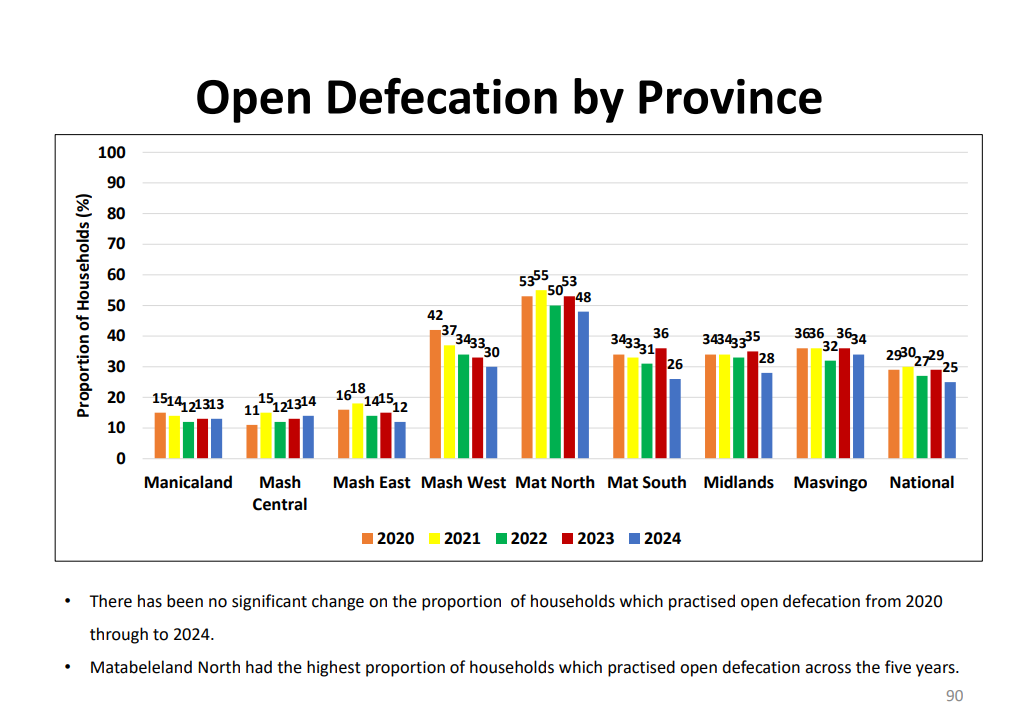

Matabeleland North is experiencing a persistent sanitation crisis, with the highest proportion of households practising open defecation for five consecutive years, according to a concerning revelation in the 2024 Zimbabwe Livelihoods Assessment Committee (ZimLAC) Rural Livelihoods Assessment Report.

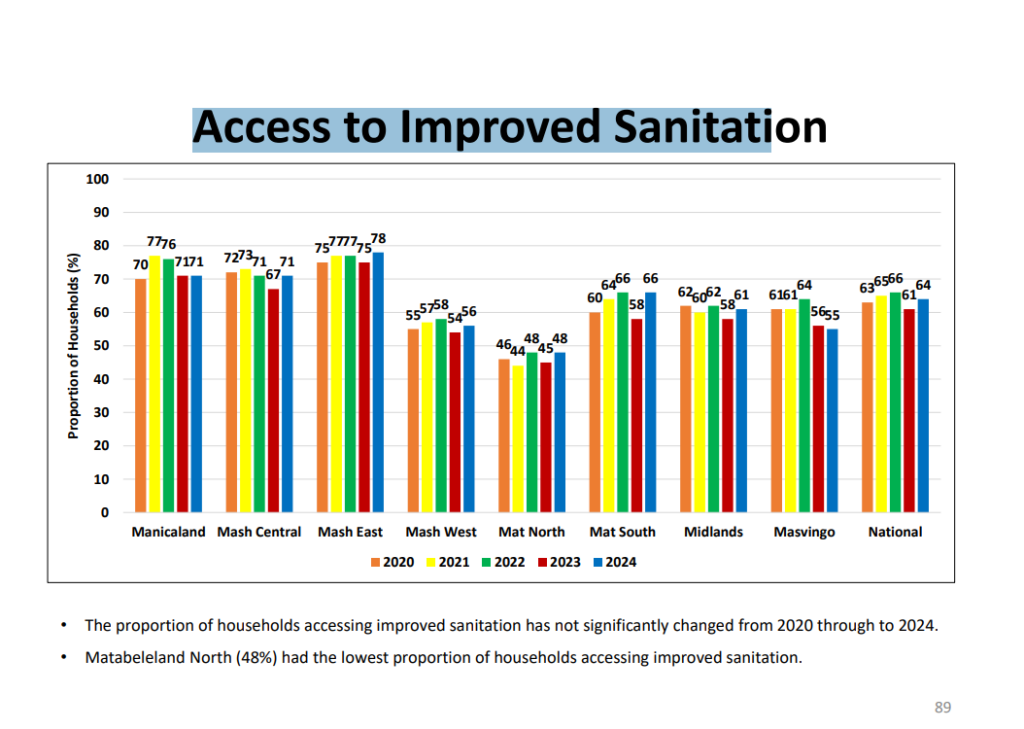

Furthermore, Matabeleland North also has the lowest proportion of households with access to improved sanitation facilities, with only 48 percent of households possessing such amenities.

ZimLAC reported that the proportion of households accessing improved sanitation “has not significantly changed from 2020 through to 2024.”

Improved sanitation facilities are defined as those that make sure there is hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact.

According to the ZimLAC report, Matabeleland North has consistently reported the highest rates of open defecation among Zimbabwe’s provinces with no significant change in the proportion of households practising open defecation from 2020 through 2024, underscoring the persistent nature of the issue.

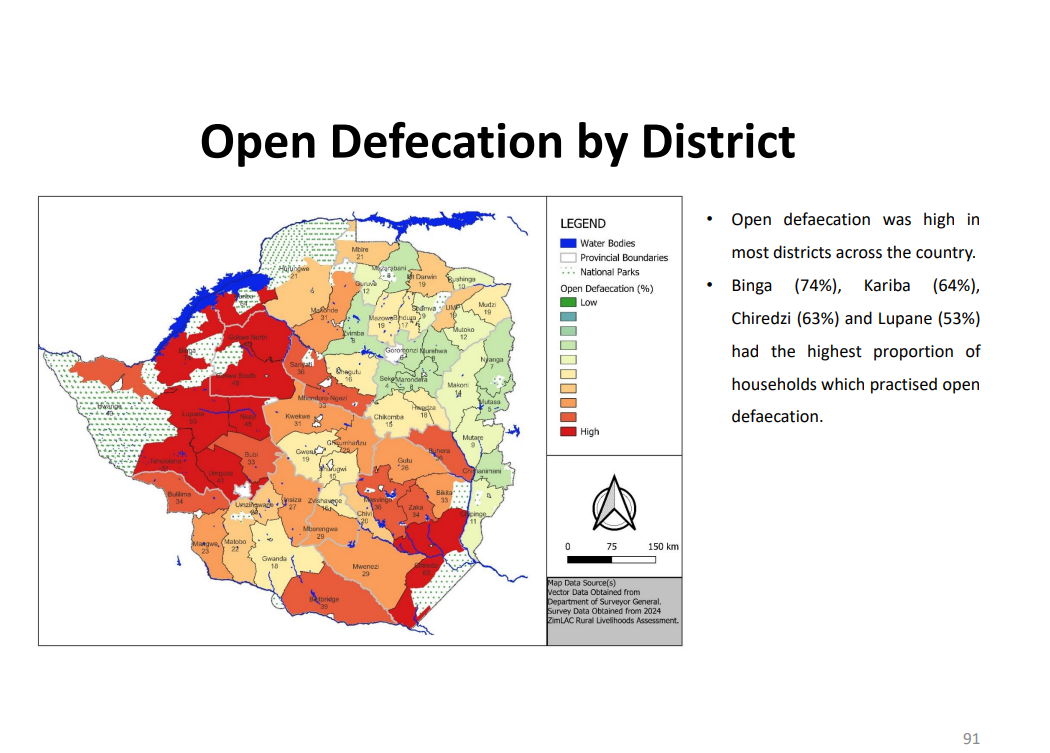

Open defecation was high in most districts across the country, with Binga (74%), Lupane (53%), Kariba (64%) and Chiredzi (63%), topping the list of districts grappling with the problem.

The ZimLAC report calls for a multi-sectoral approach to address the sanitation crisis, touching on the need for behaviour change and to encourage community-led initiatives to construct and use improved sanitation facilities.

The role of traditional leaders is also highlighted as crucial in enforcing sanitation programmes through local by-laws and penalties for open defecation.

Coordinator of the Matabeleland Institute for Human Rights (MIHR) Khumbulani Maphosa, said open defecation is a longstanding practice that has persisted due to several reasons, lack of awareness being one.

“If we are to tackle the problem of open defecation from a systems approach, we need to first look at the issues of access to information. Do people have access to quality credible information on the dangers of open defecation and alternatives to address the problem?” he said.

“Is that information accessible in their languages and in a manner that can relate to different people?”

The environmentalist noted financial limitations also prevent many households from constructing their toilets or latrines as the cost of building materials and labour is often prohibitive for families living in poverty.

“Most of our people are impoverished to the point that when they have to choose in investing in sanitation services and other needs, they will settle for other needs,” Maphosa said.

“If you look at the pricing of cement and other sanitation construction equipment or materials in the rural areas, further from metropolitan areas like Bulawayo and Harare, the more expensive cement and roofing material becomes.

He added that settlement patterns and environmental factors were another cause of open defecation as the cited areas have a “lot of vegetative cover or forest areas.”

“The vegetative cover is still very thick, so people can have the luxury of not having toilets and go to the bushes, unlike if you go to Matabeleland South which is a semi-desert and deforested area,” Maphosa claimed.

Lack of enforcement is another challenge, Maphosa cited.

“Are there enough enforcement mechanisms to enforce proper sanitation and toilet facilities in these rural areas? Are health committees that educate people and make enforcement functional enough? Do they know their mandate?”

Maphosa said the ethnic and linguistic minority component of communities mentioned in the ZimLAC report should also be considered.

“We need to promote social education and human rights in the local languages of the people. If you look at other services such as education infrastructure, and schools in these ethnic minorities, the level of education plays a critical role in promoting proper sanitation and hygienic practices,” he added.

“These are communities that still have makeshift schools. Levels of pass rate and education are very low. The appreciation of proper health and sanitation practices also correlates with the people’s levels of education.”

Maphosa added the continued practice of open defecation has severe health implications, contributing to the spread of diseases such as diarrhoea, and bilharzia, among others.

“There are certain diseases that we should not have in this day and age but we continue having,” he said, adding “so these communities are continuously going to be affected.”

Furthermore, Maphosa noted rural communities are constantly stigmatised, discriminated against, and labelled as “dirty and backward.”

“Access to toilets is one of the things that really should define civilisation and modernisation but our communities will continuously be labelled as primitive and backward, which is really unfortunate,” he said, noting how rural people face prejudice because they lack the fundamentals of self-actualisation and self-determination, which includes the enjoyment of a right to good sanitation and cleanliness.

“When someone comes to Bulawayo and is said to be coming from Binga, Lupane or Kariba people will say, ‘oh those who don’t have toilets, those who are still practising open defecation,’ it becomes a really serious issue.”

Maphosa believes continued defecation demonstrates Zimbabwe’s failure to define itself as a country.

“What kind of state are we? At some point we want to pretend like a social welfare state then pretend like a capitalist state so we need to create conditions of economic prosperity which will allow people to get services wherever they are, whenever they want them at non-inhibitive costs,” he said.

“We need to prioritise these communities in terms of our development, fiscal and policy planning.’

Devolution is also critical, said Maphosa because communities need to lead themselves.

“These local communities need power to be able to manage simple things such as health, hygiene and sanitation services within their area of jurisdiction,” he said.

A rural development advocate, Ndodana Moyo, concurred one of the primary reasons for the high rates of open defecation is the lack of adequate sanitation infrastructure.

“Many rural areas do not have access to latrines or other basic sanitation facilities,” he said, citing inadequate water supply as another cause.

“The scarcity of clean water complicates efforts to maintain hygiene and sanitation. Without a reliable water source, maintaining even basic sanitary facilities becomes challenging.”

World Food Programme (WFP) Assistant Executive Director, Valerie Guarnieri, who recently toured parts of Matabeleland said water and sanitation remained a priority in the region.

“Nutrition, sanitation, education – all of these pieces are pieces in the puzzle that we are trying to solve, so we need continued support and stamina to be able to mount this multi-sectoral response and then maybe just last is that it can’t stop with response,” Guarnieri said.

Helpful information 😊

Helpful information I’m glad 😊