Child mortality statistics at Mpilo Central Hospital in Bulawayo increased between January and March before decreasing in April this year, despite reassurances from the Ministry of Health and Child Care that it was doing “everything” to protect pregnant women and unborn children.

Mpilo recorded a total of 280 child deaths in the first four months of this year, with neonatal deaths accounting for the majority. Neonatal deaths occur within the first 28 days of life, a period when children are at the highest risk of death due to prematurity, birth asphyxia, infections, birth defects, and kernicterus, among other causes, most of which are modifiable.

Child mortality refers to the deaths of children under the age of five and is often reported as the number of deaths per 1,000 live births. Studies show that in low and middle-income countries, close to half of the mortality in children under the age of five occurs in neonates.

In 2019, 2.4 million children died globally in their first month of life, with children born in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia carrying a ten times higher risk of death than those born in high-income countries.

Aside from neonatal fatalities, other causes of death at Mpilo Hospital were classified as fresh stillbirths, macerated stillbirths, and deaths under five years.

According to information sourced by CITE from the hospital under the Freedom of Information Act (FIA), 92 children died in March compared to 49 in January this year. In February, 84 children died, and in April, 55 children died.

The hospital reported seven fresh stillbirths in January, two in February, seven in March, and two in April. Fresh stillbirths occur within a few minutes or hours of birth. There were 12 macerated stillbirths in January, 18 in February, 18 in March, and 11 in April. Maceration means the baby had been dead for hours or days in the womb.

Neonatal deaths, which caused the most deaths, totaled 22 in January, 43 in February, 34 in March, and 23 in April, with a total of 122.

For deaths under five years, the hospital recorded eight in January, 21 in February, 33 in March, and 19 in April, totaling 81.

During this period, the Ministry of Health and Child Care reported that Mpilo Hospital recorded approximately 2,500 deliveries, with almost 1,000 requiring surgical intervention.

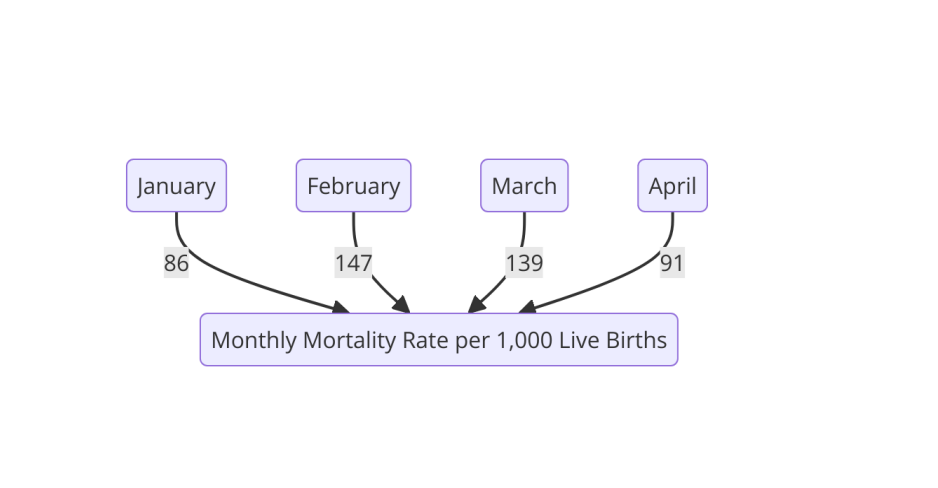

The mortality rate per 1,000 live births for each month is as follows:

Therefore the mortality rate per month is:

Mpilo Hospital attributed the causes of stillbirths to “antepartum hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), and cord accidents.” The most significant contributing factor to these deaths, according to the hospital, is “delay in seeking medical help by pregnant mothers.”

The causes of neonatal deaths were listed as “prematurity, birth asphyxia, respiratory distress syndrome, and congenital abnormalities,” according to Mpilo. Causes of pediatric deaths were “respiratory conditions, gastroenteritis, neonatal sepsis, and malnutrition.”

Efforts to obtain more detailed information on the causes of child mortality were unsuccessful as Mpilo’s administration did not respond, despite involvement from the Zimbabwe Media Commission (ZMC), which is mandated by the law – FIA to appeal for information on behalf of media outlets.

Meanwhile, Bulawayo MP Dr. Thokozani Khupe questioned the Minister of Health last week about the government’s position on hospital user fees for pregnant women.

“Part of the reason why women die while giving birth is due to user fees for pregnant women because they cannot afford to pay and end up not going for prenatal care,” Khupe said.

In response, Minister of Health and Child Care Dr. Douglas Mombeshora claimed the government had long abolished user fees.

“Our policy is to ensure anything related to pregnancy is treated for free in public hospitals, including blood and blood products,” he said. “We have a voucher system to give pregnant women coupons for free blood access. If you find someone overzealous trying to charge, please report it for disciplinary action. Pregnant issues are to be dealt with for free in public hospitals. Private hospital payments are separate.”

However, hospitals still require women to cover other costs related to childbirth, such as medication.

The combination of financial strain, overburdened health systems, and resource shortages has made accessing antenatal care a significant challenge for some expecting or pregnant women in Bulawayo and other parts of the country.

Pregnant women in Bulawayo said they are facing significant challenges in accessing antenatal care, primarily due to the high costs of user fees and limited healthcare resources.

Coupled by Zimbabwe’s struggling economy and widespread poverty, many women are unable to afford the fees required at clinics and hospitals, putting their health and that of their unborn children at risk.

“Consultations, and essential services, like ultrasounds and blood tests are expensive for low-income families,” said Marilyn Ncube of Cowdray Park Suburb, who is six months pregnant.

“I went for check ups ku first trimester. The clinic books you at US$20. However they don’t have the facilities to check if the baby is in position or alert you of any abnormalities. So you have to go to a facility that offers an ultrasound scan.”

Ncube said the facility she went to for the ultrasound charged US$30.

“In addition you need to do at least one more, especially when you are almost due because they need to know if the baby is in position. Throughout the pregnancy you need to take supplements which are not readily available at the clinic,” said the expecting mother who added these can up to US$60 for two months, that is omega 1 and 3, folic acid, ascorbic acid and other multivitamin acids.

“I have to choose between buying food for my family or going for my antenatal check ups and it’s hard because the cost of living is going up. It’s impossible to keep up.”

Ncube’s assertions show that some women, especially in high-density areas, either delay or forgo necessary antenatal check-ups altogether, which also affects the state of unborn babies.

Interviews with other women revealed that for those who manage to pay, long queues and understaffed clinics further complicate access to care.

With health facilities overwhelmed and lacking adequate resources, a number of women seek alternative, sometimes unsafe, options for their antenatal care and report to hospital late, which Mpilo officials cited as contributing factor to stillbirths.

In a written response to CITE, the Ministry of Health and Child Care expressed concern about the loss of lives, especially children, at Mpilo.

“Three-quarters of the deaths occurred during pregnancy, delivery, and soon after birth,” the ministry said. They noted that Mpilo, as a referral institution, sees a high number of severe cases referred from other institutions.

The ministry is implementing various programs to strengthen the health system. Causes of macerated stillbirths (22%) include infections such as syphilis, high blood pressure in the mother, and congenital abnormalities. Early booking and quality antenatal care can reduce these. Causes of fresh stillbirths (7%) are usually due to factors around birth, with 70% of these babies already lost by the time they presented at the facility. Early presentation at health facilities is crucial.

The ministry said early neonatal deaths (42%) can be categorised by the weight of the baby, with 53% weighing less than 1 500g. Many of these were delivered at other facilities or at home. Preterm babies need specialized care, and Zimbabwe’s health sector has faced a high skills flight, reducing available personnel. The ministry is training healthcare workers and procuring essential equipment.

Under-five mortality (29%) was attributed to infections within the first month of life, diarrhea, and respiratory conditions.

Dr. Themba Bulle, a General Practitioner in Australia with over 35 years of medical experience, emphasised the need for clean wards, good food, beds and blankets, clean water, good hand hygiene, incubators, monitors, ventilators, suction machines, weighing scales, and blood pressure machines for managing pregnant women and small babies.

He noted that good healthcare is crucial before, during, and after pregnancy.

Dr. Bulle highlighted the importance of midwives in reducing neonatal mortality. “Shortages of midwives lead to neonatal mortality. Proper teaching is necessary for young healthcare workers. Financial issues and restricted diets for women can lead to complications during and after birth.”

He also stressed that health is a critical issue requiring the cooperation of all parties, including mothers, babies, medical staff, and politicians who finance and supply equipment. The input of nurses and midwives is vital for effective hospital management.