By Nokuthaba Mathema

As the sun dipped below the horizon, casting a cloak of darkness over a rural outpost in Zimbabwe, a chorus of faint rustling of leaves and the gentle swaying of branches set in.

The rhyme of the swashbuckling of leaves is from a trudge by a herd of elephants making a beeline passing through homesteads in village 3, Hwange area, in Matabeleland province of Zimbabwe.

The elephants’ massive frames navigate through the thick darkness, tromping on everything that comes their way as they are drawn to the alluring aroma of the villager’s crops ready for harvest.

This is the daily reality of villagers like Primrose Moyo settled on the boundaries of Hwange National Park, the country’s biggest animal sanctuary. Due to the recurrent climate change-induced droughts, the villagers have to share their harvest with elephants and other wild animals the latter having the biggest chunk

“It is like we are now planting for the elephants as they get the biggest share from our crops, despite our efforts to scare them off. Some farmers no longer plant crops because its defeating the whole purpose of planting,” said Moyo.

Gogo Soneni Sithole is another farmer living in village 3 in Hwange, north of the Hwange National Park. For generations, her family has relied on farming as their main source of sustenance. However, in recent years, the once-harmonious co-existence between humans and elephants has been disrupted, plunging her into a distressing human-wildlife conflict that has deeply impacted her life.

While in the past the elephants could be scared off and run away from the humans, now they are becoming more hostile in their quest for scarce food, resulting in humans being killed while trying to guard their fields.

And Gogo Sithole a widower now fears for her family’s safety.

“Sleepless nights have become the norm as we listen anxiously to the trumpeting sounds of elephants nearby, hoping they would not venture too close to our huts. I really can’t blame them, they are desperate for food,” she said.

In village 3 of Hwange, desperation looms over the residents like a dark cloud. With each passing day, the relentless rampage of elephants brings them face to face with a sombre reality.

The fields that once nurtured dreams and sustenance now lie in ruins, a heart-breaking testament to the destructive force at play.

Primrose, like others in the village, finds herself caught in a harrowing battle for survival, her hopes and livelihoods trampled-literally-by the elephants and baboons. Amidst the chaos, she yearns for a glimmer of hope to guide her and several other villagers through this relentless struggle and restore a sense of security to her shattered world.

“The presence of elephants and baboons in our fields poses a significant threat to our means of survival, as we heavily rely on farming for sustenance. Their destructive behaviour leaves us uncertain about how to sustain ourselves and survive,” added Primrose

Elephants overcrowding in Hwange National Park

Apart from the recurrent climate change-induced droughts that have seen water and food sources in Hwange National Park getting scarce, forcing wild animals to stray to neighbouring villages, the elephant population in the conservancy has been ballooning over the years, overwhelming its carrying capacity.

A senior parks official and dedicated wildlife conservationist, who preferred anonymity, revealed that the elephant population has outgrown the size of the park.

“Zimbabwe currently has got an elephant population of about 80 000 to 90 000 elephants,” the senior parks official stated, adding; “The largest elephant population in Zimbabwe is found in Hwange National Park, with approximately 45 000 to 65 000 elephants calling it home.”

“Records showed that the population once reached 100 000 in the 1980s,” the official continued; “and during that time, culling was allowed.”

However, the official reveals a pressing concern. “The elephant population has exceeded the carrying capacity of the park,” they explained, their voice tinged with worry. “This has led to issues of human-wildlife conflict, especially in the areas surrounding Hwange National Park. In the past, the elephant population used to be controlled through culling.”

“While elephants should not be extinct as they are key on the ecological food chain, we are witnessing the ballooning of the elephant population,” the official lamented.

“Yes, the country benefits from tourism like game viewing. However, from game viewing alone, the community will not benefit. Entry fees and other proceeds will go to the state and private operators. There is a human cost to that tourism,” he said.

“Because the tourists will come and pay entry fees into the park, the absence of hunting means the CAMPFIRE project will also collapse,” the official added, concern evident in their voice. “Therefore, elephant conservation and dare I say, conservative hunting should also be considered.”

The official’s plea resonates with hope for a sustainable future.

“By embracing these approaches, the community and the country will reap the benefits. It is an opportunity to reduce the burden on the community while simultaneously addressing the challenges posed by the growing elephant population.”

Reflecting on the pressing issues that threaten wildlife populations, Alfred Sihwa, Director of the Sibanye Animal Welfare and Conservancy Trust shares his concerns with unwavering candour.

“We still have a large (elephant) population, but unfortunately, there is a decline in numbers over the years,” he reveals, his voice tinged with a mix of urgency and sadness. “One of the major factors contributing to this decline is low rainfall. Elephants demand copious amounts of water for their survival and reproductive success. Thus, addressing water scarcity becomes an imperative area of focus.”

At least 160 elephants died between August and December last year due to droughts in Hwange National Parks, according to Tinashe Farawo, the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority spokesperson, who added that more could also fall victim to the food and water shortages.

“We have been doing tests, and preliminary results show that they were dying due to starvation. Most of the animals were dying between 50m and 100m from water sources,” Farawo told the Guradian in January this year.

Shifting the spotlight to the broader context, Sihwa underscored the shared responsibility in conserving elephant populations. “Furthermore, we must acknowledge that elephants are a shared heritage among neighbouring countries, we must work collaboratively to ensure their survival and well-being.”

Thriving Tourism sector

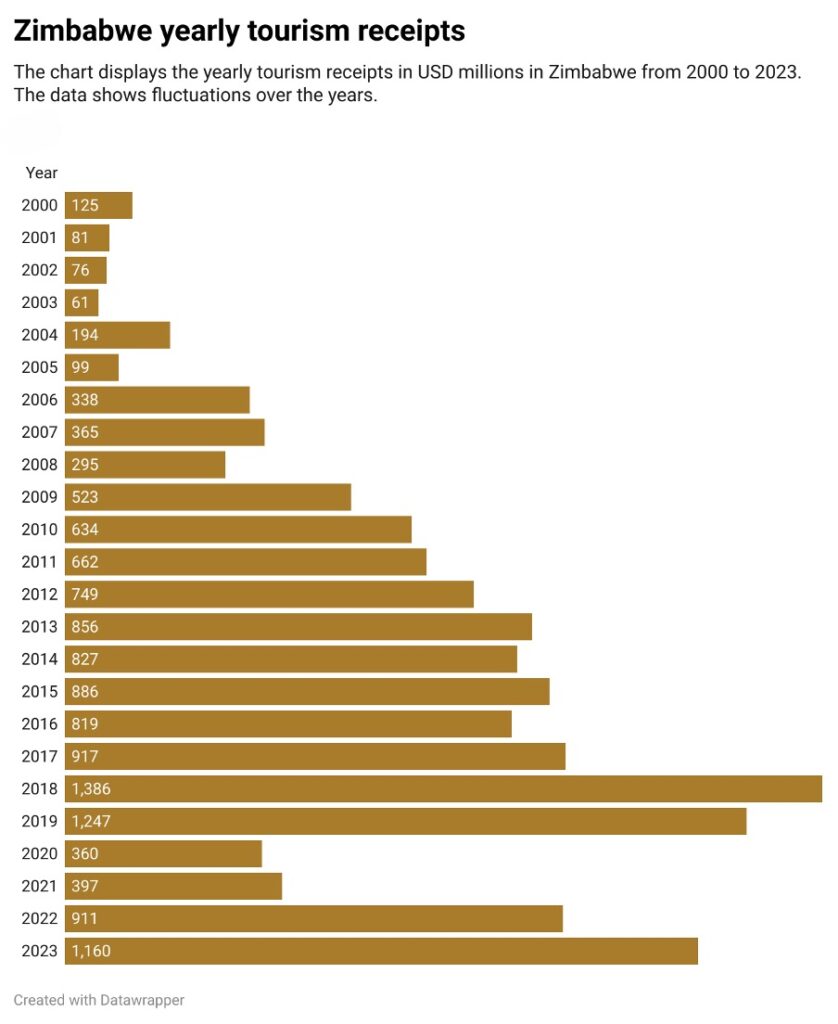

Tourism in Zimbabwe is a vital sector and holds significant potential to contribute to the country’s economic recovery. Currently, it ranks as the third largest industry after mining and agriculture. Zimbabwe boasts a diverse range of national parks, natural attractions and cultural heritage sites that make it an appealing destination for tourists.

“Tourism can be a powerful driver of economic growth, job creation, infrastructure development, cultural preservation and regional development, making it an important contributor to overall economic development in many countries. But in Zimbabwe the tourism has remained relatively at its potential stage with limited impact on the economy,” said economic commentator Reginald Shoko.

Exploring Zimbabwe’s Tourism Revenue: A comprehensive overview of tourism proceeds in Zimbabwe, measured in millions of USD, spanning from 2000 to 2023.”

Human Wildlife Conflict Relief Fund

The Ministry of Environment, Climate and Wildlife in Zimbabwe recently unveiled plans for the establishment of a Human Wildlife Conflict Relief Fund (HWCRF). This initiative aims to provide crucial support to individuals affected by conflicts between humans and wildlife in the country.

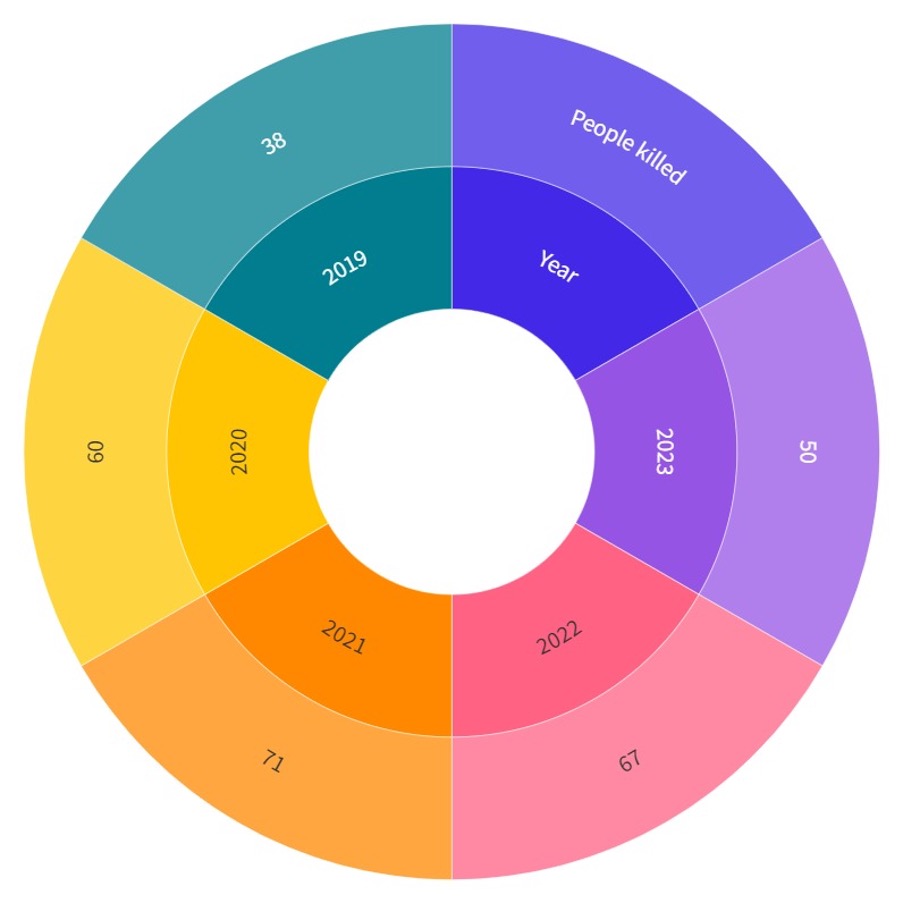

According to Zimparks close to 300 people were killed by wild animals and 308 injured between 2019 to 2023.

Human-wildlife conflict claims lives in Zimbabwe: A look at the number of fatalities between 2019 and 2023.

Dr Sithembiso Nyoni, the Minister of Environment, Climate and Wildlife, stated that the fund’s primary objective is to extend assistance to the families of those who have lost their lives due to wildlife encounters. Additionally, it will offer relief and support to individuals who have sustained injuries or disabilities due to such conflicts.

“The HWCRF has completed the initial reading in parliament and is awaiting promulgation as an act of law. This important step is necessary for the fund to be activated and commence its operations effectively,” said Nyoni.

The fund management will be entrusted to the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks), which will collaborate with local communities. This partnership ensures that the fund’s resources are allocated appropriately and that the affected communities have a voice in decision-making processes.

By establishing the Human-Wildlife Conflict Relief Fund, Zimbabwe demonstrates its commitment to addressing the challenges faced by individuals impacted by human-wildlife conflicts. This initiative is expected to provide much-needed support and mitigate the negative consequences of such encounters, fostering coexistence between humans and wildlife in the country.

But for villagers like Primrose, all these benefits from tourism and conservation do not make sense if the elephants are affecting not just her livelihood, but her security.

“It is now a matter of when, not if, we are going to get another fatality from the attack by the elephants,” she said, supporting her head with her hand.

Nokuthaba Mathema is a Zimbabwe-based journalist and alumnus of the Oxpeckers #WildEye training programme titled The Nexus of Data and Environmental Journalism. The programme and this investigation are supported by the Fojo Journalism Education Programme, incorporated under International Media Support and Fojo Media lnstitute’s Media Nexus Programme 2022-2025 in Zimbabwe, funded by Sida .