Deka River, a tributary of the Zambezi River, has been heavily polluted with metals, industrial pollutants released by local and foreign-owned coal mining as well as power generating companies, compromising the health of thousands of villagers.

Domestic and wild animals have also not been spared by the contamination of one of Matabeleland North’s major rivers, amid concerns over poor monitoring by the Environmental Management Authority (EMA).

Some villagers have over the years suffered from skin diseases, stomach pains and diarrhoea after consuming the water.

Aquatic life has also succumbed to the pollution with fish deaths being recorded over the years.

An investigation by CITE in collaboration with Information for Development Trust (IDT), under a project meant to support investigative reporting focusing on the accountability and governance of foreign interests and investments in Zimbabwe and Southern Africa has established that water in Deka River is unfit for human and animal consumption.

Deka River, situated a few kilometres from Hwange Town, supplies water to villages such as Zwabo Mukuyu, Mashala, Shashachunda, Kasibo, Mwemba, and flows all the way to Zambezi River.

Over the years, pollution from the operations of Hwange Colliery Company Limited (HCCL) and Chinese companies licensed to mine in its catchment area, has devastated Deka.

The Zimbabwe Power Company (ZPC), which operates thermal power stations in Hwange, has also contributed in a major way.

A sewer treatment plant is also contributing.

EMA revealed there are nine mining companies operating in the Deka catchment area, “which are directly and indirectly” contributing to the river’s contamination.

Tests prove contamination

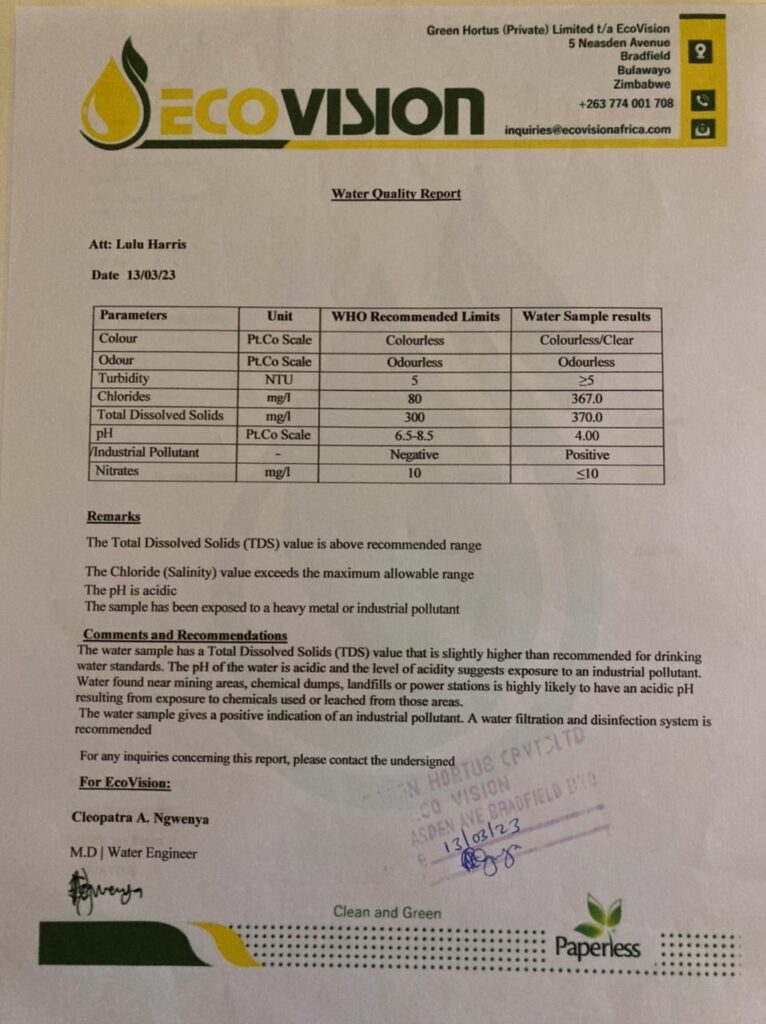

As part of the investigation, CITE tested samples of water from Deka River at Ecovision, a reputable laboratory in Bulawayo. The organisation also interviewed affected residents, community leaders, environmentalists and EMA officials.

The water samples were collected in March at a time, villagers said the pollutants were at their lowest after being diluted by inflows from the rain.

The tests however confirmed the presence of industrial pollutants and total dissolved solids (TDS) in the river. TDS are dissolved particles such as salts, minerals and metals found in all non-pure water sources. They were found to be above the permitted range for drinking water standards.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in a background document for Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality published in 2003 recommends a TDS limit of 300. Samples from the Deka River recorded 370, indicating a high concentration of minerals generated by pollution, industrial waste and mining.

According to WHO, these hazardous minerals accumulate in the body because it cannot excrete or use them, causing gastrointestinal disorders such as stomach pain and diarrhoea.

Some Hwange residents consuming water from Deka River confirmed suffering from stomach pains and diarrhea.

The WHO also says high TDS in water may also lead to kidney disease, liver illness, and in severe cases – death.

A platinum cobalt method test, which is a precise method, which uses spectroscopy to test impurities in water, revealed Deka River has a pH level of 4, whereas the normal range for pH in surface water systems is 6.5 to 8.5 and for groundwater systems 6 to 8.5.

Water with a pH less than 7 is considered acidic and when it is exposed to certain chemicals and metals, it often makes them more poisonous than normal, causing fish death and livestock deformities.

EMA, environmentalists and villagers confirmed fish death in the river.

The laboratory report recommended water filtration and a disinfection system for Deka River because “water found near mining areas, chemical dumps, landfills or power stations is highly likely to have an acid pH resulting from exposure to chemicals used or leached from those areas.”

During a second site visit in April, the news crew noticed that Deka water had turned dark green, whereas in March it was not as green. Villagers attributed the difference to rains that had fallen early in the year which had had diluted the water, at the time of the initial visit.

Villagers Speak Out

Hwange villagers said illnesses and livestock death were common.

Fanuel Mwembe (35) of Zwabo Mukuyu Village, who had 30 goats, said all of them died over time in 2014 after drinking from Deka River.

“I noticed the goats were weak and couldn’t walk after drinking the water. Some of the goats even gave birth to kids with no fur or the kids had longer legs than normal,” he explained.

Hwange District Veterinary Services Officer, Dr Lovemore Dube, said scientific evidence was needed to confirm the exact effects to livestock caused by water.

“We are dealing with a situation of conflict,” he said.

“Also people use the water, eat the fish, so the health department has to be involved. A holistic approach is needed and will be happy to be part and parcel of the research.”

Brandina Nyoni (67), another villager, said in 2020, she sought medical attention after experiencing abdominal pains, first at St Patricks’ Hospital, then at Hwange Colliery Hospital where tests revealed she had helicobacter pylori.

“My stomach was painful and I even developed wounds in my anal area. After talking with other women in the village, we suspected it was the water from Deka because several of them experienced similar pain. I was told at the hospital that I have acids and ulcers,” she said, holding her medical report.

A medical article published by Oxford Journals in 2000, says helicobacter is a common bacterium. An estimated 50 percent of the world’s population has been estimated to be infected.

Helicobacter causes chronic gastritis and has been linked to a number of serious gastrointestinal illnesses, including duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer.

The article says appropriate nutritional status, particularly frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables and vitamin C, appears to protect against helicobacter infection; however, food prepared under less-than-ideal conditions or exposed to contaminated water or soil may raise the risk.

Overall, poor sanitation, low socioeconomic status, and crowded or high-density living situations appear to be associated with a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection, a finding that suggests poor hygiene and crowded conditions may facilitate transmission of infection, as seen in Zwabo Mukuyu Village where villagers lack access to a reliable source of clean water.

Another villager Benita Tshuma added: “due to the acid in Deka water, sugar beans took longer to cook and would boil for hours.”

Rosemary Shoko in her fifties from Shashachunda Village, said when growing up, Deka water was safe but had been poisoned over the years.

“When we fetch water from the river, we notice pollutants and realised we have to stop drinking it,” she said, adding their livelihoods had been negatively affected.

“We used to weave baskets from the reeds, fish for food but now most of the fish are poisoned. We have tried to engage the mines but we don’t receive a response. All they care about is mining.”

Shoko added that some women with “delicate skin reacted after bathing with Deka water.”

Community leaders add their voice

Chairperson of the local water committee at Zwabo Mukuyu Village, Senzeni Zulu, believes the green colour in Deka indicates that mining companies had recently discharged their waste.

“The water turns green mostly around October and November when it’s about to rain because mining companies hope the rain will wash away their discharge,” she said, adding, “every time the companies see clouds or hear from the weather department there will be rain, they discharge waste.”

Zulu said EMA officials informed villagers in March that Deka water was “very dangerous.”

“When one walks barefoot on the river, their feet turn pale. If you have a wound on your feet, the itching gets worse when one gets in contact with the water and it takes longer to heal because of the acid there,” she stated.

Zulu said EMA should order mining companies to construct their own dams where they can discharge their waste.

Village head of Zwabo Mukuyu Village, Tshokwani Pinos Shoko, said due to the dire water situation, he was compelled to drill a borehole using his funds.

“I paid US$2 930 to drill a borehole. I now have to purchase a solar and submission pump but these are plans for next year. Hopefully, when functional people can come and fetch water here,” he said.

Shoko said boreholes were a viable alternative to Deka water.

However, there is only one functional borehole drilled by Hwange Colliery Company Limited (HCCL) but sponsored by World Vision for a nutritional garden.

“Some people have also dug their own water ponds to avoid using water from Deka. At least Hwange Colliery has drilled boreholes but they need to be fixed,” he said.

The village head said while water pollution had been there previously, it had worsened following the coming in of Chinese mining companies, which he accused of being reckless.

“EMA has authority and must regulate these mining companies so that they care for people,” he said.

Residents Associations; stakeholders blast EMA, HCCL and Chinese companies

Coordinator of Greater Hwange Residents Trust, Fidelis Chima said despite scientific studies pointing to pollution of Deka River, the government and EMA, were not taking action.

“Yes, Deka is heavily polluted. We have heard of people actually suffering from skin disease after using water from Deka River,” he said.

“We expect the government to make sure they actually put a stop to the continuous pollution at Deka River. However, as an organisation, we are thinking of litigation so that there is finality at the end of the day.”

Greater Hwange Residents Trust seeks to give Hwange residents a collective voice to demand accountability from duty bearers and local companies.

Chima said Deka River was the biggest source of domestic water in Hwange such that even companies like ZPC and HCCL relied on it.

“The pollution is mainly caused by coal activities from Chinese companies like (Sunrise) Chilota (Corporation Pvt Ltd), Zimberly (Investments) and many others,” he said.

“We also have Hwange Colliery and ZPC Hwange. They also contribute to the pollution.”

Sunrise Chilota’s Managing Director, Chilota Allen Mpofu said his company was aware of the pollution in Deka River but said cases of pollution “date back beyond our existence as a mining entity”.

Mpofu said when operating, his company draws water from one of Deka’s tributaries, which it uses for dust suppression and recharging washing ponds. He however said the company’s coal washing facility is a closed circuit adding the company does not discharge into the environment.

“The communities have engaged our company on several occasions and checked our processes to verify if we are polluting the water bodies,” Mpofu said.

“…The pollution affects our goodwill and cooperate image. It is unfortunate that when you travel along Deka road we are one of the two coalmines that you see and the next thing you see blue-greenish water in Deka River. It is easy to attribute the colour of Deka River to us, as we are one of the two visible mines. We are suffering from bad publicity because of the pollution occurring upstream. As a matter of fact, we have been closed for over two years and this blue colour has been occurring in Deka River but is unfortunate we are given the blame because the Deka road passes by our mine.

“We utilise a closed-circuit policy and we do not discharge into the environment. The water used for coal washing is recycled and the water in the active mining pit is pumped to another un-used pit. So, we don’t discharge any effluent into the environment. We have enough measures and facilities to contain all our processed water inside the mine.”

A translator for Zimberly Investments, Leon Ling, denied their company caused pollution, and blamed another company mining next to Deka River.

“No, it’s not us. It’s another company, we stopped mining and there’s another mining company there. We are closed and moving, no more mining. I see another company mining there next to the river,” he said, claiming his company shut doors “two to three months ago.”

“We not dumping through water. We have finished,” he said.

HCCL did not respond to questions.

Chief and Managing Consultant at SustiGlobal Environmental Consultancy, Oliver Mutasa, who provided consultancy services to a number of Chinese companies that are accused of discharging effluent into the Deka river, stated that a multi-sector approach was required to address this issue.

He said while a number of companies can be named and blamed for the pollution, scientific proof was needed to know how much each company was discharging.

“We can blame a lot of them, yet it’s only one culprit,” Mutasa said, adding that EMA must make sure companies conform to Section 5(1) of the Statutory Instrument (SI) 6 of 2007 (Effluent and Solid Waste Disposal) Regulations, which stipulates the limits of effluent discharge.

“There must be remedial measures. Before waste is discharged, some form of pretreatment is required. If EMA is not capacitated enough to make sure those companies comply with regulations, obviously the miners will definitely continue to pollute.”

Mutasa said most mining companies do not subscribe to international standards, so if there is no push from EMA, they may continue polluting, which disadvantages companies that may want to invest.

“Due to EMA’s incapacitation to profile each of these mining companies, it makes sense for people to accuse mostly Chinese-run companies for polluting the water,” said the consultant.

“It is unfortunate that the Chinese companies are getting most of the blame, but I wouldn’t want to say the Chinese only are responsible. No, I think we have got the amount of players there.”

According to Daniel Sithole of Green Shango Environmental Trust, a Hwange-based environmental organisation, precipitants from old underground mining, where heavy metals ooze into Deka River are one of the main sources of pollution.

“When there is that interaction, water stability is affected leading to serious contamination of the water,” he said.

Sithole said the increased scale of mining operations in Deka’s catchment had worsened pollution.

He said the pollution dates back to the 1990s caused by an Acid Mine Drainage from “old abandoned coal mines by HCCL, with effluent from power generation and other coal mines along the catchment area.”

To reduce pollution in the river, Sithole said, HCCL had planted reed beds, considered an environmentally friendly method of water treatment because reeds accommodate different species that digest organic matter in effluent.

Sithole said cases of fish death have been recorded since the 1990s and as the pollution load increased, there were notable fish deaths in 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2019.

We are constantly monitoring: EMA

EMA Matabeleland North Provincial Environmental Manager, Chipo Mpofu-Zuze, said over the past 13 years, four fish deaths were recorded particularly at the bridge along Deka Road.

She said this was at the onset of the rainy seasons in 2008, 2016, 2018 and 2019.

Mpofu-Zuze acknowledged EMA has “from time to time” received concerns about mining companies polluting the Deka River.

“In each case, the agency has engaged relevant offices such as the Veterinary Department who deal with animal health and the Ministry of Health and Child Care in cases of human health as they are better placed to conclusively confirm if the issues are attributable to the river’s pollution,” she said.

Mpofu-Zuze based on routine environmental monitoring through ambient water monitoring of six sampling points in and around Deka, EMA has no record of Chilota and Zimberly “pouring” their effluent into the river.

“At the time of receiving the allegations, the two companies did not have such a license because Chilota Mine has not been operational since 2020 and Zimberly have a ‘closed system’ which means all their process water is recycled back into the plant without discharging into the environment hence the licenses are not currently applicable,” she said.

She admitted that Chinese coal mining companies were contributing to the pollution of Deka, especially during the rainy season because of runoff, but said HCCL and the Zimbabwe Power Company were the main polluters.

“A 2018 study by the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) linked the colouration to water quality changes caused by the mixing of two effluent streams Runduwe and Sikabal, resulting in an increased contaminated runoff from areas where coal material had accumulated leading to pollution,” Mpofu-Zuze said, noting this is “the main unavoidable challenge with coal mining worldwide.”

“Besides the HCCL Acid Mine Drain, ZPC effluent and Baobab Sewer Treatment Plant, during a period of dry spells or no rains, there are no other direct point sources of pollution into Deka River or the effluent receiving streams that flow into Deka. It is only during the periods of heavy rains with peak surface runoff where non-point sources of pollution are relevant to Deka River pollution.”

As part of its mandate, EMA has 347 sampling points where it conducts a Monthly Ambient Water Monitoring Programme on all major rivers in Zimbabwe, of which Deka was part, said the EMA official.

“Monitoring is done on three points representing the upper, mid-river segment and downstream. Over and above, there are three other points on the Sikabala Stream, an effluent stream that flows into Deka River. All these points are strategically monitored to establish the water quality of the water bodies within the coal mining industry in Hwange where the allegations were made,” she said.

Mpofu-Zuze said there are nine-coal mining and processing entities in Deka’s catchment, whose activities both directly and indirectly add pollutants to the river.

“In addition, effluent from other sources such as sewage treatment facilities and other non-point sources including coal fines find their way into Deka River, the main water body receiving effluent from the mentioned sites in Hwange,” she said.

Mpofu-Zuze said Deka river is seasonal and flows mainly during January to May and for the greater part of the year, “the river’s flow is mainly from Runduwe Stream containing effluent from ZPC and Sikabala Stream containing effluent from HCCL Acid Mine Drainage.”

However, ambient tests on Deka River showed that most parameters are within recommended limits except for manganese, which the EMA official attributed to the Acid Mine Drainage effluent.

“As the river progresses further downstream, the water quality improves owing to the natural assimilation capacity of the river,” Mpofu-Zuze said.

According to WHO, drinking water with high levels of manganese for a long time may cause “weakness, anorexia, muscle pain,” and other neurological dysfunctions.

Manganese is also said to cause discolouration of water.