A large population of Zimbabwe accesses water from safe and protected sources although there is a huge disparity between urban and rural populations, according to the data contained in the 2019 Multiple Indicator Clusters Survey (MICS) report produced by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT).

Although this sounds optimistic especially at a time when the country, and the rest of the world, is fighting the Covid-19 pandemic, reality is far more distressing.

Considering that for cities like Bulawayo taps have been dry for most of 2020, these statistics may not be reflective of the reality of water struggles in the country’s urban areas.

According to the MICS report, 19.6 percent of the rural population still fetches their water from unprotected sources compared to 1.8 percent in urban areas. The report was compiled from 44 597 household members across the country’s ten provinces.

Section 77 of Zimbabwe’s Constitution states that “every person has a right to safe, clean and potable water and the State must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right.”

However, lack of key water sources, water resources and treatment chemicals have forced citizens, mostly from rural provinces to turn to unsafe water sources

“Kezi is a very dry area,” said 54-year-old Mpiyabo Ndiweni.

“We have gone for many years without enough or proper rainfall. They say this year its promising. In some years we end up fetching water from the same sources where our animals drink.”

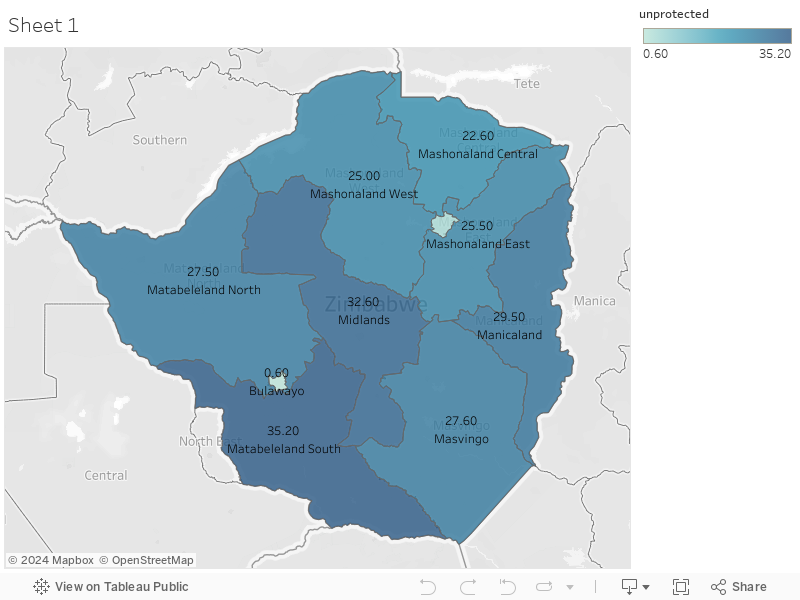

The national average of the population that fetches water from unprotected sources is 14 percent.

In urban areas, a large population, 54 percent, has their water delivered into their homes and yards through municipal or government pipes.

The rest of the urban population has an option of public taps (9.4 percent), tube wells (18.2 percent), and tanker trucks (0.8 percent).

“We only receive water once a week for 24 hours if we are lucky,” said Sethule Ncube, a Luveve resident in Bulawayo.

“Sometimes they delay giving us water for that week as scheduled and we have to run around and fetch it from boreholes around.”

Although creating an optimistic view on urban areas, the statistics also conceal the fact that residents must supplement the water that they had saved by buying from private suppliers.

“We are now spending a lot of money on water,” said Killian Tshuma of Entumbane suburb in Bulawayo.

“We lack the capacity to store enough water for our domestic use. As a result, we end up buying from other people; it could be from other houses or places where there are boreholes.

“It is a serious cost because we don’t have much money. As it is with this lockdown, it gets worse. We have no source of income, and since we spend most of our time at home, we tend to use a lot of water. We have to maintain the hygiene standards so that our homes don’t become death traps.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the inefficiencies of local authorities in making sure that all people are safe and receiving clean water.

Acting Bulawayo Provincial Medical Director, Dr Welcome Mlilo acknowledged that due the water crisis people are failing to meet their sanitary requirements.

“Science says washing hands under running water is one of the most preventative measures against Covid-19 but if there’s no running water that is a challenge,” he said.

WHO emphasises that over and above social distancing, another critical way of preventing Covid-19 infections is maintaining high levels of hygiene including washing hands regularly.

In rural areas, the larger population (38.5 percent) rely on tube wells for water.

Access to safe water or unsafe water seems to be determined by class and its indicators like the education of the household head and wealth status.

Household heads who never went to school, only 2.1 percent and 2 percent received water from a tap in the house or delivered to the yard, respectively.

A household head with a certificate, diploma or degree gained after secondary school, 33.4 percent and 10.2 percent had water delivered into the house or the yard, respectively.2.9 percent accessed water from unprotected sources.

Of the poorest Zimbabweans, none received water from a tap inside the house or in the yard, and 28.3 percent of them accessed water from unprotected sources.

Of the richest, 44.9 percent received water in the house, 15.6 percent from a tap in the yard and only 0.1 percent fetched water from unprotected sources.

Despite enduring several seasons of drought culminating in the worst water challenges in 2020, Bulawayo’s population largely receives its water from protected sources.

According to the MICS report, 66.8 percent of the population have water delivered into their dwellings through municipal pipes and 26.4 percent see it delivered into the yards.

In the country’s second-largest city, no one accesses water from unprotected sources.

This contrasts with the capital city, Harare, which is another largely urban province, where 3.2 percent of the population fetch water from unprotected sources.In Harare, according to the MICS report, a paltry 16.4 percent obtain water into their dwellings through municipal and government pipes.

In the capital city, 11.5 percent collect water in the yard, 16.6 percent from a public tap, and 30 percent from a tube well.

A human rights activist and prominent water, Khumbulani Maphosa, said it is an indictment on Zimbabwe that the capital city had such a poor record in terms of providing residents with clean water.

“And this becomes more clearer as we try and battle Covid-19,” he said.

“These urban centres, especially the capital are likely to be hotspots. This makes us doubt the statistics that are thrown around. There is no serious testing to tell us how people without access to clean water to cook their food, let alone wash their hands, are managing.”

In Manicaland province, 8.7 percent receive water in their dwellings, 7.7 percent into their yard and 1.6 percent from public tapes.

Of all the people surveyed in the province, 9.4 percent fetch water from unprotected sources.

In Mashonaland Central province, 4.1 percent receive water in their dwellings, 2 percent into their yard, and 41.7 percent from tube wells. About 13.3 percent receive water from unprotected sources in the province.

In Mashonaland East province, only 1.9 percent access water delivered into their dwellings, 2.1 percent have water delivered to their yards, 28.6 from tube wells and as high as 20 percent collect water from unprotected sources.

In Mashonaland West province, 8.5 percent access water delivered into their houses, 6.7 percent into their yards, and 34.7 percent access the precious liquid from tube wells. About 16.3 percent collect water from unprotected sources.

In Matabeleland North, one of the country’s driest provinces, a paltry 4.6 percent have water delivered into their houses, 1.7 percent into their yard, and 50.3 percent from tube wells.

About 17.4 percent fetch water from unprotected sources.

In Matabeleland South province, another dry province 8.4 percent can access water from a tap in the house, 2.8 percent have water delivered into their yard and 43.6 percent from a tube well. Of the people surveyed in the province, 14.9 percent collect unsafe water from unprotected sources.

In Midlands province, 19.4 percent have water delivered into the house, 5.1 percent into the yard and 25.3 percent access water from a tube well. It is 23.6 percent of the population in Midlands that sources water from unprotected sources.

In Masvingo province, the country’s most populous province, a paltry 4.6 percent access water from a tap inside the house, 8.6 collect water from a tap in the yard and 37.9 percent access water from a tube well.

14. 8 percent of the surveyed population fetches water from unprotected sources.