By Paul Hubbard

Independent Researcher, Bulawayo

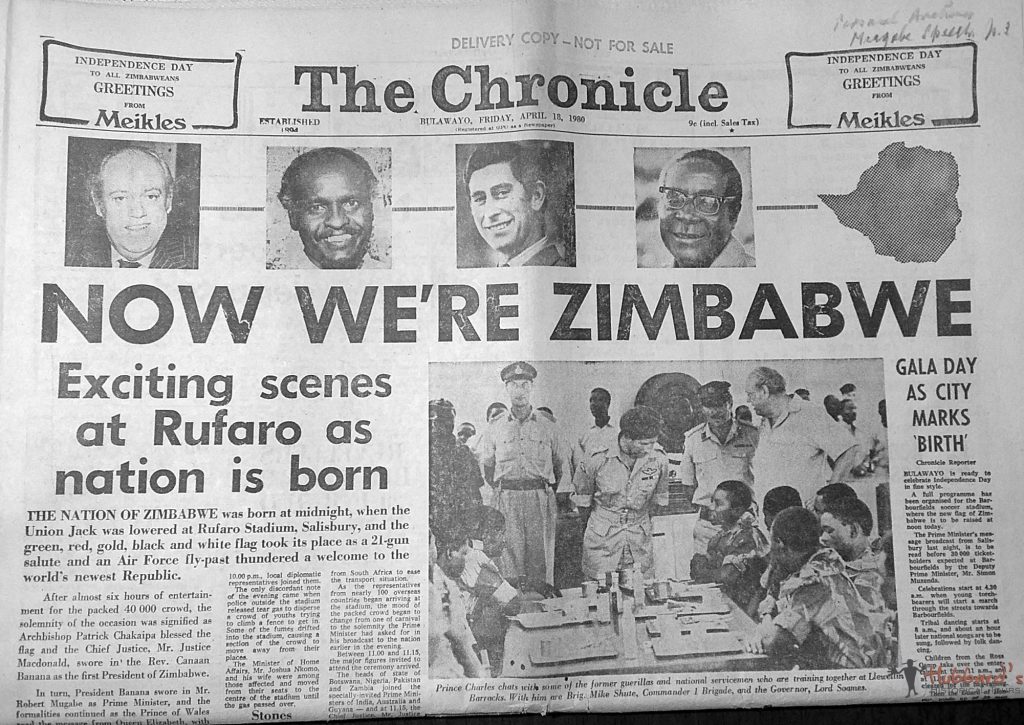

At midnight on April 17, 1980, Zimbabwe was born. As the Union Jack was lowered, the last vestige of British rule in Africa came to a sudden end. Canaan Banana was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s first president and, in turn, administered the oath of office to Prime Minister Robert Mugabe, whose Zanu-PF party had at the end of February swept to a landslide victory in British-supervised elections. Here I briefly explore the mechanics of the first election in 1980 and the Independence celebrations.

Introduction

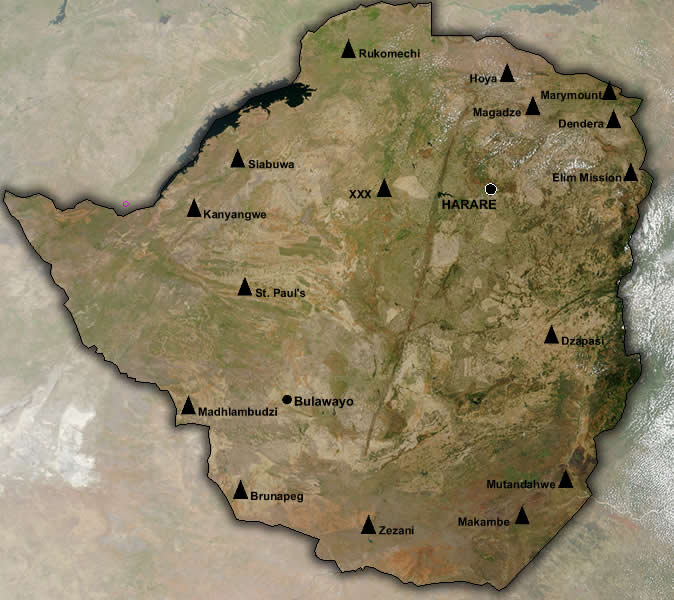

The landmark Lancaster House Conference had created a consensus amongst the protagonists which laid out the necessary conditions for peace. The ceasefire agreed that all hostilities would conclude on December 28, 1979, and the liberation forces had until January 4, 1980, to enter the rendezvous points. From there they would be taken to one of 16 Assembly Points (APs) to wait for elections. Lord Soames, the man destined to be the last colonial ruler of Zimbabwe, had arrived in the country on December 12, 1979, with the unenviable task of melding a polarised and war-torn nation into a democratic and peaceful society.

Soames’s job was made all the more difficult by the fact that Zimbabwe effectively had four armies, as well as the police, roaming about, all with conflicting loyalties and political affiliations. These included:

- Zanla (Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army), the military arm of Robert Mugabe’s Zanu (Zimbabwe African National Union), commanded by Rex Nhongo (Solomon Mujuru) and numbering about 21,000 inside the country and about 5,000 in Mozambique

- Zipra (Zimbabwe People’s Liberation Army), the military arm of Joshua Nkomo’s Zapu (Zimbabwe African People’s Union), commanded by Dumiso Dabengwa and numbering about 8,000 inside the country and 9,000 in Zambia

- the Rhodesian army and air force, commanded by Peter Walls and numbering about 17,000 regulars and about 58,000 territorials

- About 26,000 uniformed ‘auxiliaries’ (Pfumo Revanhu or Spear of the People), initially the private army of Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s UANC (United African National Council) but, by early 1980, nominally under Walls’s command

- BSAP (British South Africa Police), numbering 8,000 plus 35,000 reservists, assigned responsibility for maintaining law and order

Soames had precious little in his arsenal to contain this simmering powder keg. The Ceasefire Monitoring Force (CMF) consisted of 1,300 men, selected by the British from the Commonwealth countries of Australia, Fiji, Kenya and New Zealand as well as the UK. They were deployed within a week of the signing of the agreement, with the assistance of the US Air Force, before being taken to their lonely posts in completely unknown territory. Their task was to monitor the guerrillas in the Assembly Points as well as the Rhodesian Joint Operational Commands, provide logistical support for the APs and defuse tensions between the Rhodesians and liberation forces, who had little reason to trust each other. They monitored the peacefully increasing numbers of guerrillas in the APs with palpable relief; if hostilities had resumed they would have been caught in the middle, almost defenceless. It was an unenviable task, as much a public relations mission as a respect and confidence building exercise and, by all accounts, they handled their duty with a level of skill and tact more commonly associated with diplomats than soldiers.

Life in the country: A snapshot of 1980

Writing in mid-1980, visiting scholar, Kevin Danaher, said, “The first-time visitor to Salisbury cannot help but be impressed by the exceptionally clean and modern downtown area. The well-kept parks and spotless boulevards put any city in the United States to shame. Supermarket shelves are well stocked, and the near total absence of beggars makes one wonder if this is in fact part of the African continent.” This was only one side of the story, however, since the urban areas had remained largely untouched by the war, in stark contrast to the rural areas, where policies such as Operation Turkey, had systematically deprived rural populations of food supplies. Danaher continued: “If one stays inside the downtown area and its rich suburbs, one can easily miss the ugly truth that millions of people in this relatively affluent nation are suffering from malnutrition and that whole communities have been destroyed by starvation.” A 1979 study by the International Red Cross found that malnutrition rates in Rhodesia ranged from 13% to 29%, depending on the area. Rene Kosirnik, then head of the Red Cross delegation, estimated that roughly one-quarter of the entire population was suffering from malnutrition.

One of the striking features of 1980 (and even the 1970s) is that when looking at pictures of stores in the various areas around the country – in particular the rural areas – one cannot help but be impressed by the stock levels and full shelves. And mostly with locally-made products at that. In early February, when announcing a potential £200 mln a year trade deal with Rhodesia, the British Confederation of Industries claimed Rhodesia had 90% self-sufficiency in all sectors. Real per capita income in 1980 was R$184, although this was marred by high economic dualism; there were huge inequalities in wealth distribution between racial groups and rural-urban inhabitants. During the years of white rule, this had become entrenched by political factors, institutional considerations and systems of land tenure. The wage or money sector was almost exclusively controlled by about 220,000 whites, responsible for almost 90% of GDP, operating alongside some 2,750,000 blacks contributing the rest of GDP mainly in the form of output for their own use. However, to see these as separate systems masks the complex inter-relationships, feedback and linkage effects that made these sectors thoroughly interdependent.

| Percentage of Gross Domestic Product by Industry of Origin | |||

| 1954 | 1965 | 1980 | |

| Agriculture | 22.8 | 18.3 | 12.5 |

| Manufacturing | 14.7 | 19.4 | 25.2 |

| Mining | 8.6 | 6.9 | 8.3 |

| Construction | 7.9 | 4.6 | 3.0 |

| Public Administration | 3.9 | 5.6 | 10.6 |

| Distribution/hotels | 13.9 | 15.0 | 12.4 |

| Other Services | 28.2 | 30.2 | 28.4 |

| This table exaggerates the role of manufacturing at expense of agriculture and mining because processing of grains, tobacco, cotton, sugar and certain minerals was classified as manufacturing which obscured the extent to which the country was reliant on primary production. Also interesting is the growth of Public Administration which included defence, reflecting the growing impact of the war. |

In 1980, Zimbabwe’s population was 7.1 mln people, the labour force containing 2.75 mln people, just over half of whom earned their livelihood from non-wage agricultural activity in the subsistence economy. Formal sector employment was 1.01 mln (still below the 1975 record of 1.050 mln), while another 100,000 had casual seasonal or contract employment in agriculture. These figures show that in 1980 some 92% of the labour force was employed, albeit it at mostly menial levels, leaving an unemployment rate of 7.5%. However dark clouds were on the horizon: the labour force was estimated to grow at 2.9% a year, meaning at least 150,000 new jobs were needed a year to maintain the employment rate – a daunting task for the new administration.

The exchange rate on was R$1:US$1.54 on April 17, slipping to R$1:US$1.44 on April 22, 1980. Rhodesia’s exports, including gold, in 1979 were to the value of $700 mln, while imports were $585 mln. Inflation in 1979 was measured at 11% thanks to higher oil prices but also owing to the effects of the war and real sanctions. As to prices, The Herald cost 10c, The Chronicle was 9c, a full English breakfast with kippers at the Ambassador Hotel in Salisbury was 50c — the same price as an average classified ad in any newspaper. A lunchtime braai at Bulawayo’s Holiday Inn would set you back R$2.35 (children, half-price), a citrus tree seedling was 20c from the government nursery, a WRS FM Radio/Tape combination player cost R$132 or you could buy the same radio type but with two speakers from Supersonic for R$131. A leather handbag was R$15.99 in the shop and the cheapest summer dress was R$12. The first week of tobacco sales in April 1980 yielded an average price of 84c/kg. Sedan cars sold for an average R$2,500 if in good condition, and it cost R$2 to get into a domestic football match, or R$4 for VIP.

| Major Exports 1980 | ||

| Value Z$ Million | Share in Total Exports | |

| Tobacco | 123 | 13.6 |

| Gold | 115 | 12.7 |

| Ferro-alloys | 88 | 9.7 |

| Asbestos | 80 | 8.9 |

| Iron & steel | 73 | 8.1 |

| Cotton | 57 | 6.3 |

| Nickel | 53 | 5.9 |

| Sugar | 47 | 5.2 |

| Copper | 25 | 2.8 |

| Meat | 19 | 2.0 |

| This table highlights the high dependence of Zimbabwe on primary production. Exports and imports were dominated South Africa, while Europe – especially West Germany – received the lion’s share of overseas exports. |

Maintaining the Ceasefire and The Coup That Never Was

In the week between the agreement being signed at Lancaster House on December 21 and the ceasefire taking effect, over 100 people had been killed in the war. The death toll the following week was down to a handful, although intermittent “contacts” (as the battles between the Rhodesian security forces and the Zipra or Zanla fighters were known) continued until the end of March. Although fragile and far from perfect, the implementation of the ceasefire had at least created a climate which allowed elections to be held. For example, according to not-wholly-reliable Rhodesian statistics, between the end of December and the elections in February, 290 people were killed — an average of five a day. Based on the figures for the last three months of 1979, had the ceasefire not been in operation, the number of dead during the period would probably have exceeded 3,500.

Despite the favourable climate created at the beginning of the ceasefire by the smooth assembly process and the considerable drop in the level of military activity, the British authorities soon agreed to the redeployment of the Rhodesian forces throughout the country, even though the agreement had stated that all military forces should be confined to barracks. This was a controversial decision by Soames who partly justified by saying they had the training and equipment to get the job done. The “auxiliary forces” roamed the country at will, occupying several of the regions previously controlled by Patriotic Front forces who were now in the assembly areas. Later research has shown these forces were responsible for innumerable violations of the letter and the spirit of the agreement.

The Ceasefire Commission, delegated to investigate breaches, investigated well over 200 incidents between January and March 1980, with the Zanu-PF army, Zanla, allegedly responsible for more than half. The management of the ceasefire was totally dependent on the Rhodesian Forces, especially Muzorewa’s auxiliaries. Ceasefire monitors never left the bases where they were stationed, but relied on reports from the Rhodesian Forces on ceasefire violations, and the Governor’s official briefings to the international press corps were based solely on these reports. As a result almost all cease fire violations reported by the Governor were attributed to the Patriotic Front parties.

The run-up to the elections was a time of great tension and mass violence. The final ceasefire commission communiqué, published in The Herald of February 23, 1980, attributed the following total number of breaches, and incitements to breach: of Rhodesian Security Forces 2 and 12; Zanla 99 and 35 reported in former Zanla operational areas; Zipra 24 and 12 in former Zipra operational areas; bandits 17; unattributable 18. In the siege-like atmosphere created by the continuation of martial law regulations and the omnipresent military uniforms and arms, it is no wonder that violence continued throughout the election campaigning. The catalogue of intimidation, arrests and detention, illegal campaigning and dirty tricks was a long one. What was clear was that the rural population was mobilised and, often, bludgeoned into supporting the guerrilla army and political party active in their area.

There was a sense of outrage among the ranking military officers over events in January and February. Fearful that Zanla and Zipra were establishing a stronger position for themselves than before the ceasefire, the real danger of a coup presented itself — and some even began to actively plan for such. General Walls was aware of the dissatisfaction and his own frustrations led him to exclaim that it would be better “to blow the whole thing and get back to the war and bring the South Africans in”. Walls calmed down but many in the army were unsure, fearful or antagonistic. The assassination attempts on Mugabe are perhaps the clearest evidence of these plans. As one young Rhodesian army conscript put it, it was not ‘‘Britain has pulled it off’’, but, rather, ‘‘You Traitors. You have sold us out.’’ With the pass word ‘Tally Ho the Fox’, the plan was to attack and destroy the main combatant assembly points, lightly guarded by the CMF. Attempts would be made to blame it all on Zanla and Zanu (PF), to have them banned from participating in the election and forge an alliance with any of the other political parties left standing.

On February 14, the day of voting for the contested white seats, Salisbury was hit by bomb blasts that all-but destroyed the Presbyterian Chapel in Jameson Avenue (now Samora Machel) and Kingsmead Chapel in Borrowdale. The next day police disarmed another bomb outside the Salisbury Catholic Cathedral and found anti-Christian literature purporting to be by Zanu, obviously an attempt by the security forces to discredit the party. Even more ominous, attempts were made on Mugabe’s life, including gunfire attacks on his house (injuring two of his nephews) and a botched explosion meant to destroy his car as it entered Masvingo. Other plots included spiking a microphone with explosives in Bulawayo and an assassin waiting with a rifle near Gweru.

A false issue of the magazine, Moto, appeared on the last Saturday before the elections, carrying an inaccurate and defamatory profile of Mugabe that claimed, among other things, that he was a mummy’s boy with the nickname nzvenga mutswairo (to dodge the broom). On February 24, the day after the Moto forgery was exposed, the paper’s presses were destroyed in a bomb blast, with another attempt to make it look like a revenge attack by Zanu (PF) forces. In the final week before the election, Moto – the only newspaper in the country to fully endorse and forecast a Mugabe election victory – was unable to publish.

The logistical lead-up to Elections

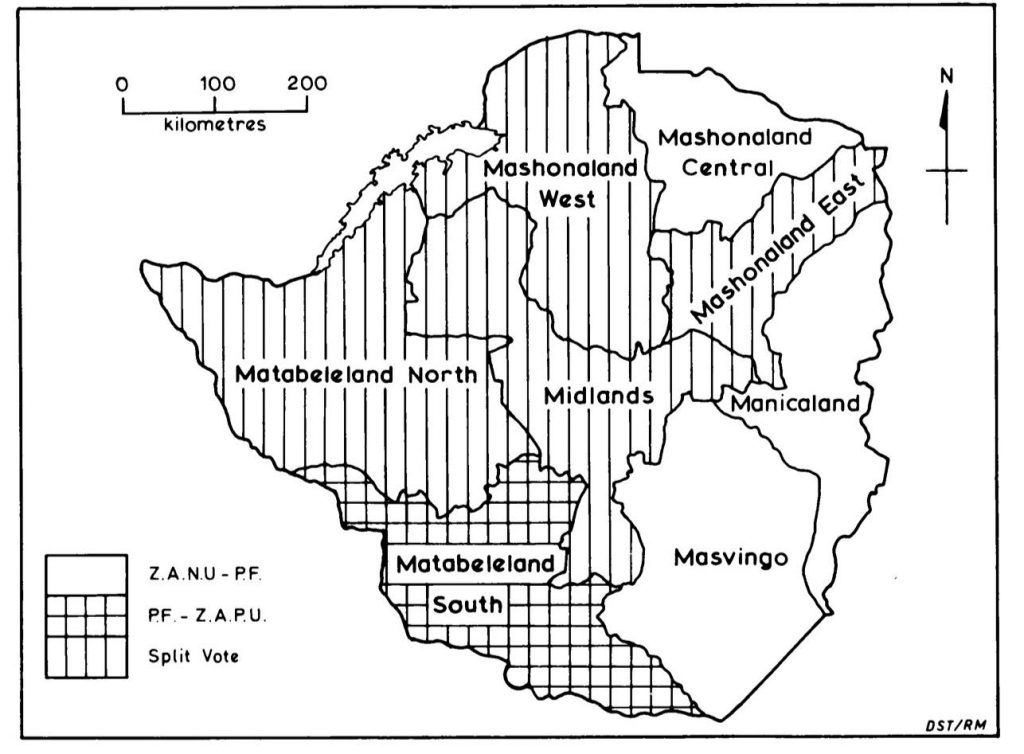

The electoral system used for the 1980 election was proportional representation. This was based on the party list system, according to which seats in the National Assembly were allocated in proportion to the number of votes that each contesting party won in each of the country’s eight provinces. A threshold of 5% was used for allocating seats in each province. This system was abandoned in the 1985 elections and replaced with the single member district or first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all system. Twenty members of the House of Assembly were to be elected by the ‘white roll’ comprising those people (mostly white) who had previously qualified to vote. This election was conducted in 20 single member constituencies which had been drawn up by a Delimitation Commission in 1978 and were the same as those used in the 1979 ‘internal settlement’ election. Voters who were registered on the white roll were ineligible to participate in the common roll election.

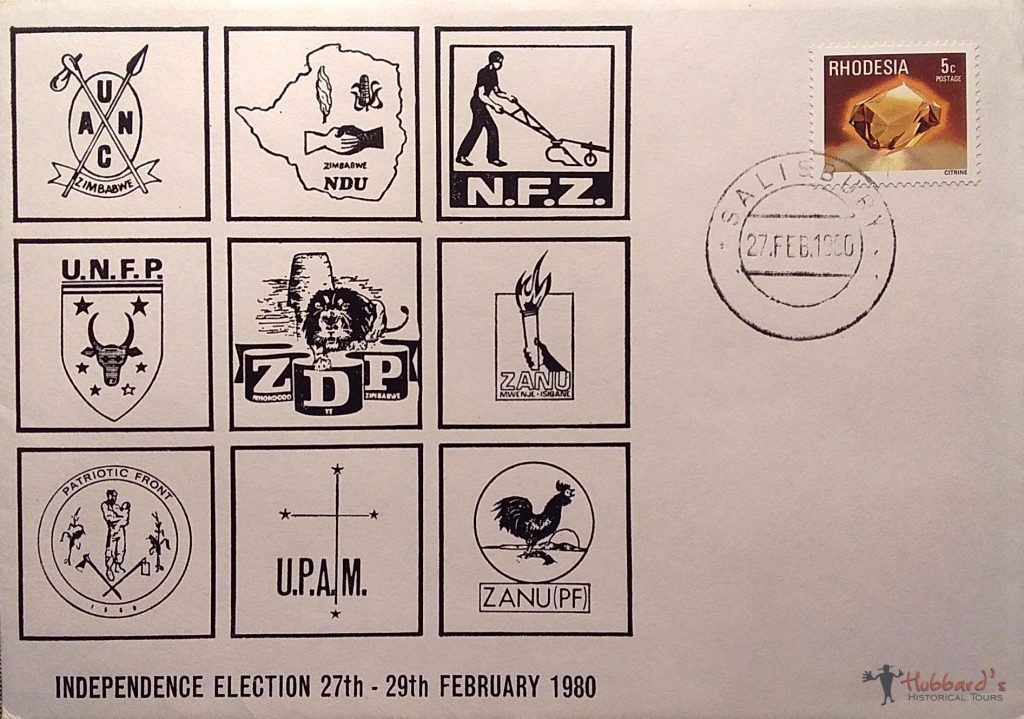

Initially 10 political parties were registered but only nine actually took part in the polls. These were the NDU – National Democratic Union (Henry Chihota), NFZ – National Front of Zimbabwe (Peter Mandaza), PF – Patriotic Front (Joshua Nkomo), UANC – United African National Council (Bishop Abel Muzorewa), UNFP – United National Federal Party (Chief Kayisa Ndiweni), UPAM – United People’s Association of Matabeleland (Dr Frank Bernard), ZANU – Zimbabwe African National Union (the Rev Ndabaningi Sithole), ZANU (PF) – Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (Robert Mugabe), ZDP – Zimbabwe Democratic Party (James Chikerema).

After his removal as party leader in 1976, Ndabaningi Sithole continued to claim to be the leader of Zanu, ahead of Mugabe. He registered his party as Zanu during the 1979 elections, winning a handful of seats and thus establishing a precedent for his legal and political claim to the name. Thus, in 1980, it was almost impossible for Mugabe to run as Zanu. The major question at the end of 1979 was whether Nkomo and Mugabe would contest the elections jointly as the Patriotic Front (PF) or as their individual parties. Senior Zanu officials claimed this alliance would cost them votes in Mashonaland, as well as obscure the truth in the debate about which party had the larger support base (and, thus, the strongest hold on power) in the country. Nkomo, hoping the decision would win him votes and promote unity, registered the name of his party as the Patriotic Front (PF), temporarily dropping the name Zapu. Mugabe, thus unable to choose either Zanu or PF, chose the amalgamation Zanu (PF).

The first election symbol chosen by Zanu (PF) was a crossed hoe and AK-47 assault rifle, however this was rejected by the electoral commission for being inflammatory and warlike. This decision of course conveniently ignored the use of so-called traditional weapons by other parties, such as the spear and knobkerrie of the UANC. The crossed hoe and gun had been used by Zanu for many years and being forced to choose a new one was a great inconvenience in a country where much of the electorate was functionally illiterate and would rely on the symbol to show them where to put their “X”. A cockerel in front of a rising sun was eventually selected and approved, signifying a new dawn in the politics of the country and heralding true independence for the majority. Hardly an innovative African motif, the simple rooster became an attention-grabber thanks to the elaborate efforts of the well-paid graphic artists. Soon, thousands of people were wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the symbol and moving their arms in imitation of a cockerel flapping its wings. “Cock-a-doodle-doo!” even became the official greeting for party supporters before the elections! (The symbol may still be seen on the top of the Zanu-PF building in Harare.)

In the areas under the sway of Zanla and, thus, Zanu (PF), an intricate network of people’s committees from village to branch to district level had been elected and taken on specialist functions, having liaised with the guerrillas for years. This network, aided by mujibas (usually youngsters who acted as eyes and ears for the guerrillas), was largely unappreciated by the authorities and the observer group. Most outsiders were ignorant of this grassroots political system but it played a crucial role in organising voting. From today’s perspective, it is fascinating to note that there was a lack of inter-party debate over policy issues. All were agreed, for example, upon the need for free primary school education, major improvements in the health service and the necessity to provide better housing for all. Much of the campaigning was, therefore, focused on the personalities and liberation war service of the candidate — a corrosive mentality Zanu-PF has been unable to escape to the present day.

The election was run by the National Election Directorate who relied mainly on members of the Rhodesian civil service for their manpower requirements. There were 657 polling stations set up across the country – 119 static, 23 mobile in the urban areas and 216 static and 298 mobile in rural areas. This favourably compares to the 685 polling stations used in 1979 but with far more mobile stations – encased in protective mine-proofed vehicles – in operation. There were over 200 official election observers from 30 countries, as well as countless journalists, unofficial observers and spectators travelling around the country. A two-stage counting of votes was planned – ballots were to be first counted “face down” in the eight provincial centres before going forward to the final count. This was done to ensure that no one could know exactly how each district voted and thus avoid reprisals from the winners – or losers. Every party was banned from singing, dancing and carrying placards within 100m of any polling station.

The 1980 elections for the black electorate were remarkable in that there was no voter’s roll (a legacy of white Rhodesian indifference to the black electorate) and to qualify to vote was ridiculously easy compared to today’s endurance rally. All you needed – as an adult male – were identity documents showing you were over 18 years old and either a citizen, born in the country or had lived in Rhodesia for more than two years. If your wife (or wives) had none of these, she (or they) could use that of their husband, provided he had been found eligible to vote. Fluorescent ink was used to mark voters’ hands and prevent repeat voting. The 1979 elections had created a useful precedent – a test-run if you will – and many people were familiar with the intricacies of the methods of voting. What was crucial, however, was that the electorate really believed that the ballot was secret. Without this, it is possible that the weight of security force intimidation and economic pressures exerted by employers would probably have worked to reduce turnout.

Each of the leaders held massive rallies in Salisbury’s Highfield Township at Zimbabwe Grounds, and to an extent these provided a barometer for the public mood. Sithole attracted a small crowd and, while Muzorewa had a fairly large turnout, there was a marked lack of enthusiasm once the free food and drink had been consumed. Joshua Nkomo attracted a huge crowd, but by far the most massive crowd yet seen in the country was that reserved for Robert Mugabe’s triumphant return to his homeland. In fact the crowd at Zimbabwe Grounds on January 27, was larger than the entire white population of the country at the time. The media campaign was a three-way battle between Zanu (PF), PF and the UANC. Muzorewa’s campaign was definitely the more lavish, aiming to dazzle the target market with style rather than substance. The contrast between the high profile, Western-style media of Muzorewa’s campaign was never more obvious than the comparison of their headquarters – Muzorewa at the luxurious Monomotapa Hotel while Zanu (PF) was comfortably ensconced in rundown, workmanlike quarters at 88 Manica Road.

Voting Begins, February 14, 27-29 1980

On February 14, 20 House of Assembly members were elected by voters registered on the White Rolls. The Rhodesian Front of Ian Smith won all these seats, 14 of them unopposed. Future Minister of Health, Dr. Timothy Stamps standing as an Independent, lost the Kopje seat in Salisbury to Dennis Divaris, but with the highest vote for any non-Rhodesian Front candidate.

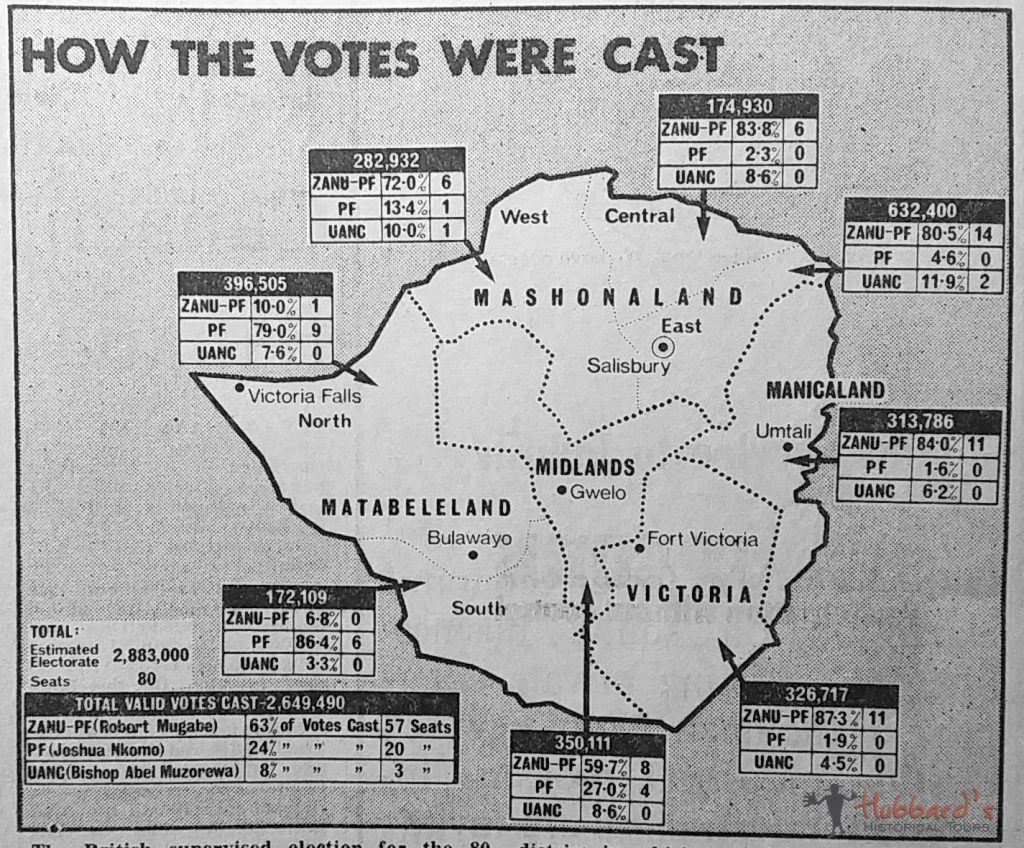

Voting in Zimbabwe’s first majority elections started on February 27. Standing in enormous queues, 886,482 people cast their vote on the first day. Mugabe, reportedly supremely confident of victory, left for talks with Mozambican President Samora Machel and Tanzanian leader, Julius Nyerere, after casting his vote. He had, along with the other party leaders, cast his ballot in his home constituency of Mashonaland East. Abel Muzorewa symbolically signed his ballot with the same pen he used to sign the Lancaster House Agreement. On the second day of polling, the turnout reached 2,028,586 beating the final figure for the 1979 elections. By the end of the third day, 2,649,529 people had cast their vote — an unprecedented level of turnout, far exceeding the 1.87 mln turnout over five days of polling in 1979.

A peaceful transition of power was not really expected. The results of the 1980 elections in Zimbabwe, which produced a transition to Independence under a government of the two wings of the Patriotic Front, surprised almost everyone. There was a feeling that the divisions which had led the two wings of the Patriotic Front to fight the elections as separate parties, plus the pressures from Rhodesian security and British officials who were running the elections, would produce another puppet regime or a stalemate, prescriptions for a neo-colonial state or for violent turmoil.

There is the question of whether the effect of political events on the activities of a Stock Exchange is overrated. During the Lancaster House Conference the Rhodesian Stock Exchange (RSE) steadily climbed, later helped by high mineral prices (especially gold) as well as the announcement of duty-free access to the European Common Market from March. Nevertheless, some settling occurred as political events unfolded. On February 12, for example, the Industrials stood at 343.74, 48.84 points below its January 8, peak, a 12.5% drop. The Minings index fell 18.86 points (7,1%) to 249.83. In early March, the RSE took a drastic downturn after nervous speculation that Zanu (PF) had won the election but brokers dismissed the anxieties saying the market had to settle after the upturn before elections. This was reflected on the day results were announced, when shares firmed after falling due to the initial shock of a Zanu (PF) victory, closing the day 10 points (2.9%) down on 346.41. International opinion on the London bourse was not as sanguine, as Rhodesian government bonds 1965-70 fell from £123 to £110 while Lonrho shares fell 8p to 103p. In February, the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia Dollar (as it was known) was worth US$1.47 and ZAR1.23. In early March, it was revalued down by 4% against all currencies except the rand to make imports cheaper and eliminate the cross-rates gap.

| Companies Listed on RSE, February 1980 | |||

| Industrial Financial & Commercial | Mining & Mining Financial | ||

| Internal | External | Internal | External |

| Afdis, Art, BAT, Border, Cairns, Capri, CAPS, Gulliver, H&S, HiPaper, Hippo, J&F, Kingston, Maceys, Mash, Merlin, Morewear, M&R, Nat Foods, N/Chart, P&C, PGI, PP Cement, Porthold, Radar,Risco, Rho-Ab, RAL, Rhobank, Rhobus, Rhocable, Rhoplow, Rhotread, Riotrust, Rothmans, RSR, SPC, Schweppes, TA Holdings, Tanganda, Tedco, Tinto Industries, TSL, Wilbrik | Blantyre, Emray | Bindura, Coros, Empress, Falcon, Mangula, Rio Tinto, Shangani, Wankie | Anglo, Lonrho, Welkom |

Producing the election results

The results were announced on March 4, at 0900, by Rhodesian Registrar of Elections, Eric Pope-Symonds. Zanu (PF) won 57 seats while the PF (Nkomo) won 20. The UANC, which had won 51 out of 72 seats reserved for Africans in elections the previous year, won only three, despite massive financial and organisational backing from Rhodesian whites, from South Africa and from international business, as well as overwhelming pressure to support the Bishop’s party exerted by the Rhodesian security apparatus. It was later said to be one of the “least cost effective electoral battles ever fought in Africa, several million pounds sown, reaped a mere three seats.” Unofficial reports have Muzorewa’s electoral campaign costing £3 million, £1 million per seat won!

| Party | Total Votes Cast | % of Votes | Seats |

| NDU | 15056 | 568 | – |

| NFZ | 18794 | 709 | – |

| PF | 638879 | 24,113 | 20 |

| UANC | 219307 | 8,277 | 3 |

| UNFP | 5796 | 219 | – |

| UPAM | 1181 | 45 | – |

| ZANU | 53343 | 2,013 | – |

| ZANU (PF) | 1668992 | 62,992 | 57 |

| ZDP | 28181 | 1,064 | – |

| Total Valid Votes | 2649529 | Spoilt Papers | 52746 |

| Total Poll | 2702275 | ||

| Election Results, 1980 | ||||||

| Manicaland | Mashonaland Central | |||||

| Party | Votes | Seats | Party | Votes | Seats | |

| NDU | 1837 | – | NDU | 1216 | – | |

| NFZ | 1283 | – | NFZ | 1086 | – | |

| PF | 4992 | – | PF | 3947 | – | |

| UANC | 19608 | – | UANC | 14985 | – | |

| ZANU | 16843 | – | UNFP | 914 | – | |

| ZANU (PF) | 263972 | 11 | ZANU | 3671 | – | |

| ZDP | 5251 | – | ZANU (PF) | 146665 | 6 | |

| ZDP | 2446 | – | ||||

| Candidates: ZANU (PF) – K. Kangai, M. Nyagumbo, D. Mutasa, W. Ndangana, F. Shava, V. Chitepo, N.P. Nhewatwa, M. Mahachi, T. Dube, C. Makoni, E. Sanyangare | ||||||

| Candidates: ZANU (PF) – E.Z. Tekere, T.R. Nhongo, F.J. Masango, S. Sekeramayo, G.Rutanhire, J.Kapanidza | ||||||

| Mashonaland East | Matabeleland North | |||||

| NFZ | 1668 | – | NDU | 1840 | – | |

| NDU | 2359 | – | NFZ | 4517 | – | |

| PF | 28805 | – | PF | 313435 | 9 | |

| UANC | 75237 | 2 | UANC | 30274 | – | |

| UNFP | 1593 | – | UNFP | 1340 | – | |

| ZANU | 9499 | – | UPAM | 729 | – | |

| ZANU (PF) | 508813 | 14 | ZANU | 3218 | – | |

| ZDP | 4466 | – | ZANU (PF) | 39819 | 1 | |

| ZDP | 1333 | – | ||||

| Candidates: ZANU (PF) – R.G. Mugabe, M. Dube, R. Marere, W. Mangwende, M. Mvenge, E. Shirihuru, E. Pswarayi, G. Ziyenge, P. Muranbiwa, J. Hunda, H. Nyazika, G. Chidyasika, A. Kabasa, S. Rambanepasi UANC – A.T. Muzorerwa, S.C. Mundawarara | ||||||

| Candidates: PF – V. Moyo, D. Mangena, S. Malunga, J. Ntuta, J. Nkomo, D. Ngwenya, R. Chinamano, J. Ngwenya, T.V. Lesabe ZANU (PF) – H. Ushewokunze | ||||||

| Mashonaland West | Matabeleland South | |||||

| NDU | 2211 | – | NDU | 927 | ||

| NFZ | 2589 | – | NFZ | 2494 | ||

| PF | 37888 | 1 | PF | 148745 | 6 | |

| UANC | 28728 | 1 | UANC | 5615 | ||

| ZANU | 4688 | – | UNFP | 619 | ||

| ZANU (PF) | 203567 | 6 | UPAM | 452 | ||

| ZDP | 3261 | – | ZANU | 694 | ||

| ZANU (PF) | 11787 | |||||

| Candidates: ZANU(PF) – R. Manyika, J. Chivaura, E. Chikowore, N. Shamuyarira, S. Mombeshore, A. Mudzingwa PF – A.M. Chambati UANC – T.G. Mukarati | ZDP | 775 | ||||

| Candidates: PF – T.G. Silundika, S. Nkomo, E. Ndlovu, B.Mguni, C. Ndlovu, P. Njini | ||||||

| Midlands | Victoria | |||||

| NDU | 2218 | – | NDU | 2448 | – | |

| NFZ | 3087 | – | NFZ | 2070 | – | |

| PF | 94960 | 4 | PF | 8107 | – | |

| UANC | 30245 | – | UANC | 14615 | – | |

| UNFP | 1330 | – | ZANU | 8938 | – | |

| ZANU | 5792 | – | ZANU (PF) | 285277 | 11 | |

| ZANU (PF) | 209092 | 8 | ZDP | 7262 | – | |

| ZDP | 3387 | – | ||||

| Candidates: ZANU (PF) – M. Urimbo, E. Zvobgo, D. Mutumbuka, S. Taruvisa, N. Makombe, S. Mazorodze, J.B. Moyo, O. Munyaradzi, N. Mawema, D. Maraire, A. Taderera | ||||||

| Candidates: ZANU (PF) – S.V. Muzenda, R.C. Hove, E.R. Kadungure, W. Munangangwa. S. Makoni, S. Mumbengewi, J. Zvobgo, S.E. Mativenga PF – J. Nkomo, C. Muchachi, C. Msipa, W. Kona | ||||||

Western journalists and other commentators offered two contrasting explanations for the results of the 1980 elections in Zimbabwe. The defeat of the UANC by the PF parties was explained in terms of immediate and short-term intimidation. On the other hand, the victory of Zanu (PF) over Joshua Nkomo’s PF was explained in terms of mythical, primordial history. The Shona and the Ndebele, it was held, were divided by ‘traditional’ tribal history and in the elections the majority Shona voted for Mugabe and the minority Ndebele voted for Nkomo. This confused legacy remains to this day and in no way helps to explain the results of the 1980, or subsequent elections.

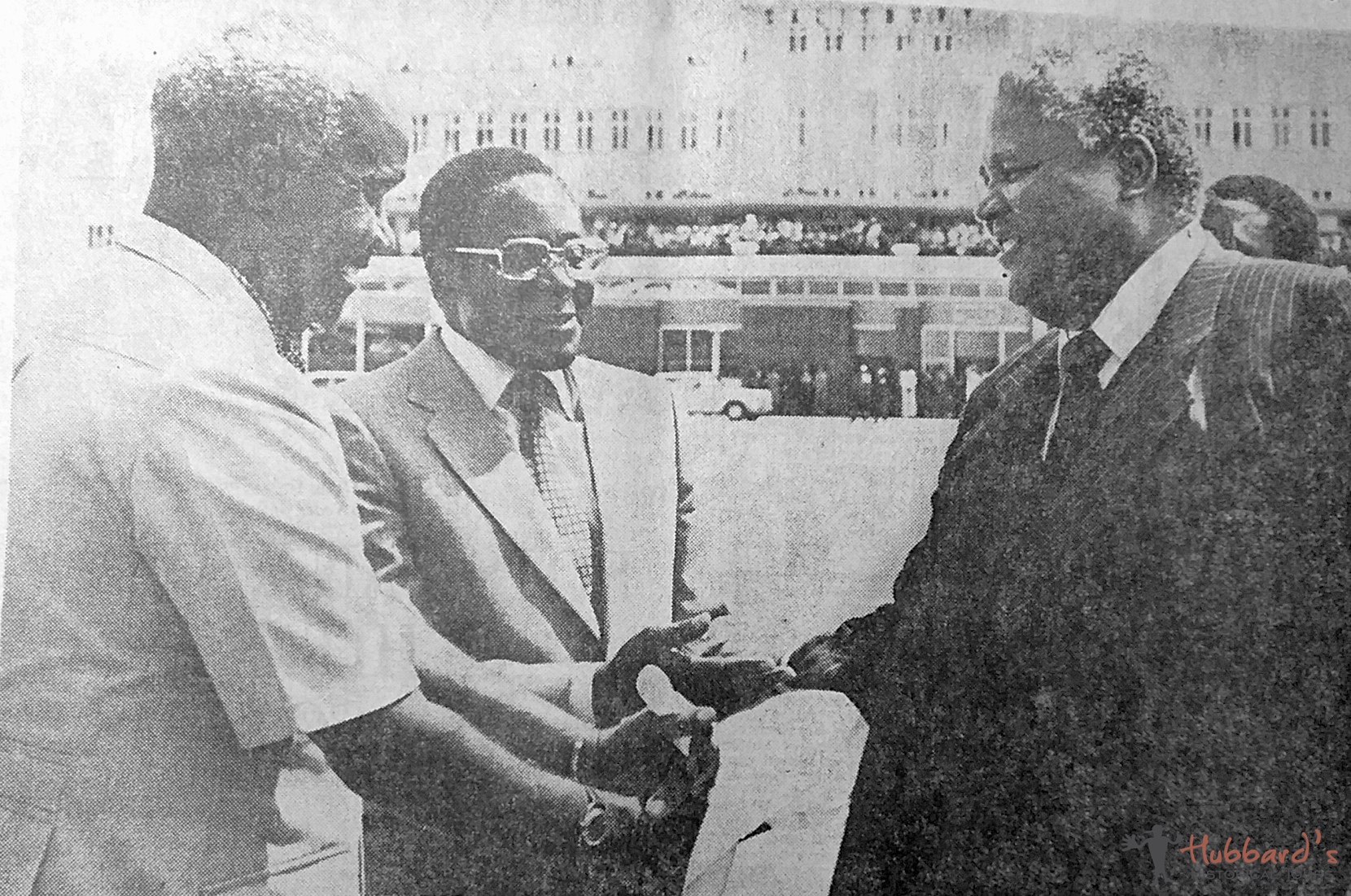

In an interview immediately after the results were known, Mugabe said “We feel very indebted to the people of Zimbabwe for having given us this support, we will live up to their expectations as much as we can. We are also very happy that our allies in the PF, Zapu, have done well and they have come second which means really that the whole contest was between the two components of the PF”. Nkomo accepted the outcome, saying “This is what we struggled for and have accomplished … We have got the country for the people and therefore everyone has to accept it”. Muzorewa said he was “shocked and puzzled” and claimed the election was not free and fair and in no way reflected the will of the people.

Mugabe began his official press conference with the following statement: “Some will be surprised by the size of the victory the Patriotic Front has won. We fought the election separately but the results go to both components of the Patriotic Front. It is a victory for the Patriotic Front as a whole. People committed to genuine independence have had the opportunity to prove to the world their allegiance to the patriotic forces. It is a moment of joy for the Patriotic Front”. The same morning Nkomo opened his press conference with these words: “Together we have won 77 seats. This is vital. Even if we have won as separate parties, it is the Patriotic Front which has emerged. We fought for Zimbabwe. We have done it over the years. Finally we have got Zimbabwe. What we have done is to win Zimbabwe. What everyone must do now is to accept the result which gives us independence. The main thing is to see that Zimbabwe becomes an independent and stable state.”

Was the election free and fair?

The Commonwealth Observer Group (COG), along with the British and Irish Government delegations declared the election satisfactory before the final tallies were even in. COG leader Rajeshwar Dayal said, that “polling… provided an adequate and acceptable means of determining the wishes of the people in a democratic manner”. It was virtually the unanimous view of the British, Commonwealth and other international observers who witnessed the elections that they were, under the circumstances, free and fair.

In his report to the Governor, the Election Commissioner concluded that, despite some distortion of voting as a result of intimidation in certain areas, the overall result would broadly reflect the wishes of the people.” Many of the observers expressed their dissatisfaction with what they viewed as irregularities such as Soames’ ’use of the auxiliary forces for peacekeeping actions, perceived British partisanship, and the threat of disenfranchising parts of the country. Even the British Election Commissioner, or Returning Officer, Sir John Boynton, said in a report that although the election was in general a reflection of the wishes of the people, it was “in no sense free from intimidation and pressure”. He continued: “My view is that in the country as a whole, the degree of intimidation and pressure was not so great as to invalidate the overall results of the poll”.

Before the final election results were in, most observers felt that Zanu and Zapu combined would win no more than 41 seats in the new parliament – a majority of the 80 black seats. (The 20 reserved white seats had all gone to the Rhodesian Front Party in elections held two weeks earlier.) Governor Soames had the power to ask any party which in his opinion could form a government to do so, however Joshua Nkomo refused to commit his party to a joint Patriotic Front government with Zanu (PF) after the election, even though Mugabe had announced his intention to do so. Muzorewa needed only 31 seats between his ANC and other African parties – there were nine in the field – to form an alliance with the Rhodesian Front to form a government with a 51 seat majority.

What no one fully appreciated, and certainly what white Rhodesians, their South African allies and the British could not understand, was the Zimbabweans’ will to be free of white rule regardless of the guise under which it masqueraded. As Sonny Ramaphal had warned, the people had voted for self-government, not good government. The whites reacted with stunned disbelief to the election results. Mugabe, the man portrayed by the government’s propaganda machine as a monster, had done the impossible and won. The mood among the majority was one of jubilation and not recrimination – the bitterness lay mainly with the whites. Some of Nkomo’s supporters bizarrely argued that the result was a plot by the UK, US, SA, China, Tanzania and Mozambique to put “their” man in power. Others, after thinking about it, said “The PF lost the election two years ago when Zanu began intensive political campaigning, using Zanla to politicise the masses”.

The new government

Mugabe and Nkomo agreed in principal to form a coalition government on March 5, and then took their time in deciding the actual composition of the various ministries and their responsibilities. Nkomo, spurning the ceremonial post of President of Zimbabwe (as it lacked political clout) had initially wanted the portfolio of Defence but had to settle for the Ministry of Home Affairs, under which the police were placed. The Cabinet was announced by Mugabe on March 11 and initially had 22 Ministers and 13 deputies. The list of people reads like a Who’s Who of Heroes Acre:

| Position | Person |

| Prime Minister & Minister of Defence | Robert Mugabe |

| Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs | Simon Muzenda |

| Minister of Home Affairs | Joshua Nkomo |

| Minister of Manpower, Planning and Development | Edgar Tekere |

| Minister of Finance | Enos Nkala |

| Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs | Simbi Mubako |

| Minister of Public Service | Richard Hove |

| Minister of Labour and Social Welfare | Kumbirai Kangai |

| Minister of Transport and Power | Ernest Kadungure |

| Minister of Local Government and Housing | Eddison Zvobgo |

| Minister of Lands, Resettlement and Rural Development | Sydney Sekeremayi |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | David Smith |

| Minister of Agriculture | Dennis Norman |

| Ministry of Information and Tourism | Nathan Shamuyarira |

| Minister of Natural Resources and Water Development | Joseph Msika |

| Minister of Education and Culture | Dzingai Mutumbuka |

| Minister of Health | Herbert Ushewokunze |

| Minister of Public Works | Clement Muchachi |

| Minister of Posts and Telecommunications | George Silundika |

| Minister of Mines | Maurice Nyagumbo |

| Minister of Youth and Sport Recreation | Teurai Ropa Nhongo (Joice Mujuru) |

| Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s Office | Emmerson Mnangagwa |

What challenges faced the new government?

There were many challenges facing Mugabe’s government, including:

- The racism and segregation which caused much of the conflict did not magically dissipate with the independence celebrations. While many of the extreme racists had fled the country, others remained, confused, embittered and scarred by war.

- Criticism of government was rising and political rivalries between the parties in Parliament were widening.

- War-torn Zimbabwean society included some one million refugees who required immediate services and eventual resettlement. This was further complicated by a once-prosperous, now stagnant economy which had suffered from the erosion of a decade of unsuccessful but damaging international embargo, as well as five years of wartime distortion and recession. The loss of over 30,000 whites during the struggle drained away skills which were needed for the rapid rebuilding of the economy, especially the agricultural sector.

- The four independent armies plus many privately-held weapons threatened the fragile political alliance. Although Mugabe ordered the integration of the armed forces, it seemed likely that many would remain outside of the national army for some time to come. The soaring crime rate was considered to be a reflection of the residual power of and conflict between these armed groups.

- Zanu (PF) was highly factionalised, reducing its effectiveness as an instrument of political solidarity. Mugabe’s control of his party was not yet firmly established, with internal factions surrounding various contenders for power, including Edgar Tekere. The ideological flavour of Zanu (PF) was not clear, although a plurality appeared to be shifting toward the centre. It was likely, as forecast by one observer, that “Mr. Mugabe won’t be the fearsome revolutionary Ian Smith warned of, but neither will he be the man of conciliation and generosity that Rhodesia’s whites think they now see.”

- Land redistribution was a vexing problem. Lord Carrington at Lancaster House assured Zimbabwe of as yet undelivered funds with which to purchase white farms, part of a Z$1 billion aid package that promised some relief.

- The role of foreign powers, especially South Africa, was still being defined. The two countries agreed to maintain economic relations and consular functions, although Zimbabwe’s determined opposition to the apartheid system was already well understood in the South African government.

Creating new icons for Zimbabwe

It was immediately clear that new national icons for the new country would be required, including a currency, stamps, name changes and corrections, a national anthem, and more. The main initial focus was to design a new flag to replace the short-lived hybrid used for only two months during the government of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. Once Soames had taken control in December 1979, Rhodesia was for a brief time a British colony again and, thus, the old flag ceased to be relevant and the British flag, the Union Jack, was used at all official functions.

The design of the new Zimbabwe flag was submitted by a government independence celebrations committee headed by Richard Hove, soon to be Minister of Public Works. Flight Lieutenant Cedric Herbert of the then-Rhodesian Air Force (and a member of the Rhodesian Heraldry & Genealogy Society), claimed that the initial design did not include the Zimbabwe Bird, and that this “was added [to the design] after I had pointed out its uniqueness and history”. On March 25, 1980, Prime Minister-elect, Robert Mugabe saw and approved the final design which was made public the following day.

First Independence Celebrations, April 18, 1980

The official date for Independence was announced as midnight of April 17. The Governor, Lord Soames, had agreed to Mugabe’s request to delay granting Independence “for a few weeks” to allow the new ministers time to familiarise themselves with their departments. The weeks after the announcement were spent in feverish preparation for a lavish, meaningful and iconic celebration.

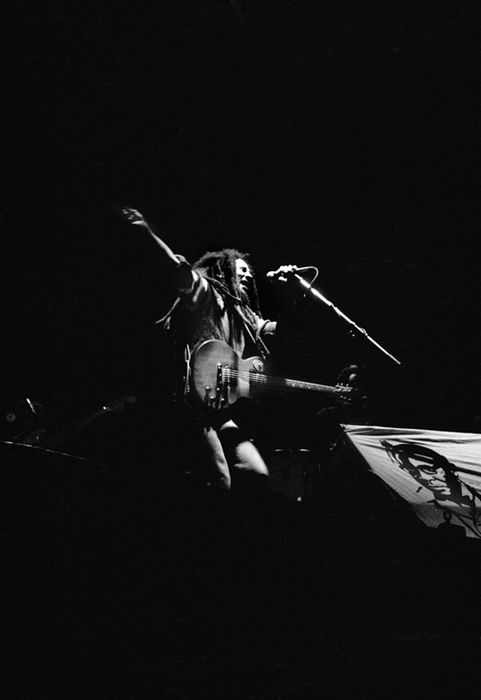

The Independence Ceremony at Rufaro Stadium involved the usual pomp and ceremony, marching bands and demonstrations on the football pitch, transformed into a parade ground for the night. The stadium was crammed with people, packed on the rising terraces around the football pitch. Everyone had to be in their places two hours before midnight. Among the local bands entertaining the crowds were Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, performing songs from their 1977 hit album Hokoyo! among others.

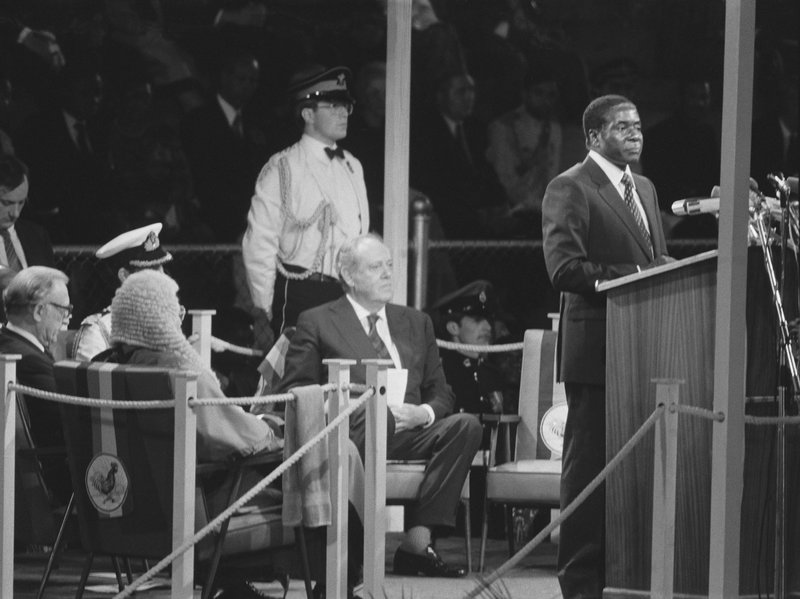

On the saluting base, built out onto the field, were the dignitaries: Prince Charles, to represent the Queen, dressed in the white uniform of a Royal Navy Commander; Lord Carrington and Lord Soames, the architects of Britain’s handover; Kurt Waldheim and Sonny Ramphal from the UN and Commonwealth respectively; Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India; Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia; Seretse Khama of Botswana; other frontline presidents and the leaders and ambassadors of over 100 countries that wished Zimbabwe well. Behind the saluting base were the benches for the junior ministers, party officials and the supporting cast of MPs, invited guests and security officials. Among them were Abel Muzorewa, PK van der Byl, Dennis Divaris, Mugabe arrived at 2340, driven in a white Mercedes, accompanied by 10 security men running alongside, followed by Canaan Banana, both arriving to thunderous cheers and applause.

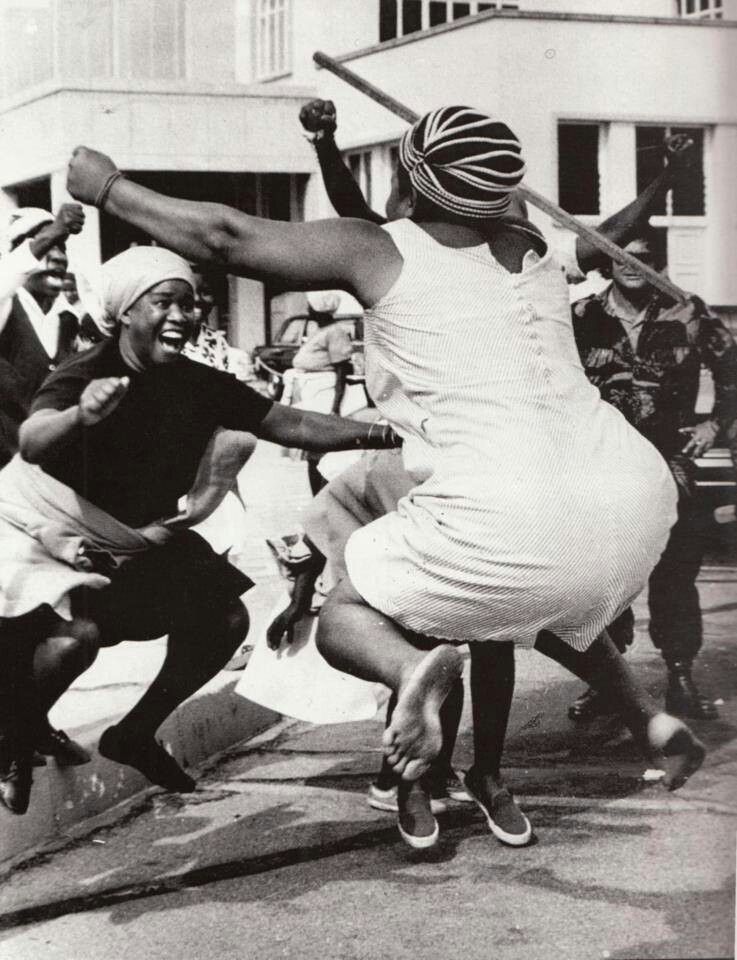

Outside the stadium swarms of people struggled to get in. The police, over-reacting, used tear-gas to repel them – even Joshua Nkomo and his wife got some in their eyes! He said in his autobiography, The Story of My Life, “But even this squalid confusion could not spoil the ceremony. Back in the 1940s at Tjolotjo Government School I had been the prize student who hoisted the Union Jack in honour of our visiting Prime Minister, the disappointingly tiny Sir Godfrey Huggins with his glittering shoes. Now for the very last time that flag came down, and the colours of free Zimbabwe broke out into the air. I am not ashamed to say that I wept for joy.”

RSM John O’Donnell of the Corps of Royal Military Police lowered the Union Jack. From the perspective of the British, the official lowering of the Union Jack had taken place in the afternoon of April 17, at Government House, when it was lowered there and handed to Prince Charles. The new Zimbabwe flag was blessed by Archbishop Chakaipa and, as the clock struck midnight, the Zimbabwe flag was hoisted by Commander Amoth Chingombe (Chimurenga name: Agnew Kambeu) of Zanla. Speaking at Chingombe’s funeral in 2008, Mugabe said of this moment, “As he hoisted the flag, his hand was firm and unyielding, clearly anxious that this precious symbol he was sending up would not slip down. Its significance was too great to tarnish by any faltering action or movement other than a straight upward pull.” As the Zimbabwe flag was raised (and saluted by Prince Charles), a 21-gun salute boomed out and smoke billowed over the stadium, packed with 40,000 revellers and guests, who roared their unmitigated approval. In that moment, the first child to be born in the new Zimbabwe emerged safely at 12:01, daughter of Mr and Mrs Musoesvi of Kambuzuma in Salisbury.

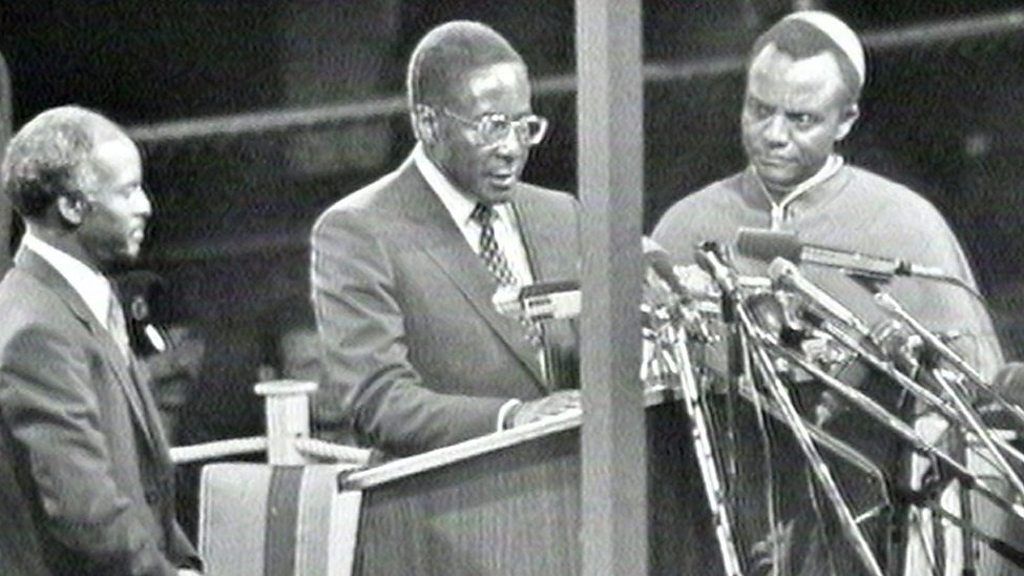

The President, Rev. Canaan Banana was sworn in by Chief Justice Hector Macdonald. Banana then turned and administered the oath of office of the Prime Minister to Robert Mugabe. Prince Charles then stood and presented the constitutional instruments of independence, documents of a symbolic nature and significance. The flame of Independence was lit by Mugabe, and immediately afterwards, runners took it to the Kopje where it was promised it would burn permanently. Later that day, Robert Mugabe pledged reconciliation, promised freedom and democracy. He spoke with electrifying eloquence of the need for Zimbabweans to unite and rebuild their country that had been ravaged by a protracted armed struggle to bring democracy to the people.

The headline event for most people however was the iconic Rastafarian musician Bob Marley and his band. Popular myth has it that Robert Mugabe had wanted to invite Cliff Richard, who performed music more to his taste. The first official words said in Zimbabwe’s Independence Era were “Ladies and Gentlemen, Bob Marley and the Wailers. Viva Zimbabwe!” Marley immediately launched into an intro, shouting “Viva Zimbabwe!” again, followed by the songs, Positive Vibration, Them Belly Full (But We Hungry), Roots, Rock, Reggae and I Shot The Sheriff. He did not complete his full nine-song setlist as a riot broke out in the midst of the fourth song. Marley did come back once everything was calm but played only a couple of songs. That night, he never got to sing his famous anthem “Zimbabwe” celebrating the country’s fight for independence. The lyrics of the song speak to the right of all people to self-determination and promised a hope for a future in Zimbabwe that has yet to be realised. Marley sang in that song: “Every man got a right to decide his own destiny / And in this judgment there is no partiality / So arm in arm we’ll fight this little struggle / Cause that’s the only way we can overcome our little trouble.”

Very informative. Zanu PF won the 1980 elections square. They wanted it the most among the lot.

I still don’t understand why Nkomo rejected the President Post (sulking) instead opting for a mere Home Affairs Ministerial post. Lack of Wisdom there on Mdala’s part.